The following points highlight the three gasteromycetes:- 1. Phallales 2. Lycoperdales 3. Nidulariales.

Order # 1. Phallales:

The Phallales are commonly called stinkhorns because of the strong foetid odour of decaying meat they possess in their exposed glebal tissue. These are some of the most beautiful fungi. They grow where there is ample organic matter such as humus, rotted tree stumps, or decaying sawdust and often in damp soil of bamboo grooves. The young basidiocarps arise as terminal swellings of rhizomorphs.

They are spherical to ovoid masses known as eggs surrounded by a firm, somewhat leathery peridium. At first the young basidiocarps are completely or partially subterranean. They contain the fertile tissue or gleba and a specialized structure known as receptacle or receptaculum with maturity of the basidiocarp, the receptaculum elongates.

The pressure caused by the elongation of the receptacle finally ruptures the peridium elevating the gleba above ground. The gleba at maturity deliquesces to a slimy evil- smelling mass with spores borne on a specialized receptacle. The receptacle may be a long, spongy pileate stipe, or a wide meshed lattice-like structure with or without a stipe.

The evil-smelling slimy gleba filled with spores attracts flies which serve to carry the spores far and wide. Two families are recognized: the Phallaceae and Clathraceae. They are distinguished on the nature of receptacle.

Family Phallaceae of Gasteromycetes:

The members of the Phallaceae are distinguished by a stout, hollow stipe. At the top of the stipe is the pileus with viscid mass of spores. The pileus may or may not be adherent to the stipe. The stipe may also develop from below the pileus, a white skirt-like net-work known as indusium (pl. indusia).

The Phallaceae include 10 genera, of which Phallus, Mutinus and Dictyophora are best known. In Phallus, the stipe elongates rupturing through the peridium.

The apex of the stipe is covered with bell-shaped pileus bearing gleba (Fig. 293E). Mutinus is very similar in structure to Phallus, but the basidiocarp is smaller, and the pileus is adherent to the stipe (Fig. 293D). Whereas, Dictyophora has in addition to stipe and pileus, a beautiful skirt-like indusium originating between the pileus and the stipe and encircling the stipe (Fig. 293B).

Both Phallus and Dictyophora have a bell-shaped pileus free from the stipe except at the top.

Genus Phallus of Gasteromycetes:

Phallus, because of its strong odoriferous slimy glebal mass, is known as stink- horn or dead man’s finger. It grows on damp soil rich in humus. Most widely known species is Phallus impudicus. Besides the typical odour of the slimy glebal mass, Phallus is well-known for its attractive basidiocarp and the mechanism of dispersal of spores by insects.

The first sign of appearance of basidiocarps is the development of ellipsoid swellings on the mycelial strands which ultimately develop into rhizomorphs of the mature basidiocarps. Each of these swellings is of uniform compact weft of hyphae which ultimately differentiate into a dome-shaped central column rising vertically from the point of insertion.

Gradually a bell-shaped layer of felted gelatinous tissue (gelatinous layer) enveloping the column, and a white membrane (outer wall of the peridium) develop.

While the whole developing basidiocarp increases in size becoming more narrowly ovoid in form, the outer wall of the peridium and the gelatinous layer grow in circumference and thickness; the central column acquires the form of a globular head supported on a cylindrical stipe. Ultimately gleba, pileus and the inner layer of the peridium are differentiated.

The stipe is at first a very narrow, afterwards a more broadly fusiform body which runs through the longitudinal axis of the entire central column from its apex to its base. The pileus carrying the gleba becomes free.

The young basidiocarp now looks like an egg (Fig. 294A) which may be semi-subterranean spherical to ovoid in shape surrounded by a tough peridium composed of two layers—the inner layer is the endoperidium and the outer exoperidium. The exoperidium is continuous at the base with the central column which forms the receptacle of hollow stipe filled with mucilage (Fig. 294B).

The stipe and exoperidium are again continuous with the rhizomorphs produced from the mycelium embedded in the substratum. The gleba arises from the peripheral layer just within the endoperidium.

The central part of the young basidiocarp is differentiated into a cylindrical hollow stipe and a folded honey-comb-like receptacle which bears the fertile part of the gleba (Fig. 294B). Within the young gleba are cavities lined by basidia bearing up to nine spores. As the gleba mass ripens the basidia disintegrate. When the spores are mature, the gleba breaks down forming a viscid, olive-green slimy mass.

A sudden increase in length of the stipe thrusts the pileus and gleba against the peridium and bursting it raises the gleba into the air. The cup-like ruptured peridium remaining at the base of the stipe is the volva (Fig. 294C & D). Expansion of the stipe is accompanied by breakdown of glycogen and its conversion to sugar.

The globe when exposed to the air undergoes auto-digestion, the characteristic foetid smell and sweet taste of the disintegrated gleba attract insects which aid in dissemination of the spores (Fig. 294E & F).

Some Indian species of Gasteromycetes:

Phallus impudicus L. ex. Pers.; P. rubicundus (Bosc.) Fr.

Family Clathraceae of Gasteromycetes:

The Clathraceae, very much similar to Phallaceae attract attention from a distance by the strong odour emitted by the slimy glebal mass which lines the inner surface of the hollow receptacle. The family is characterized by the presence of an ovoid, hollow, lattice-like receptacle.

The gleba occupies the entire interior surface of the interlocking network. The receptacle may or may not be borne on a stalk or stipe. In Simblum the lattice-like receptacle is held on a long stipe (Fig. 293C). Whereas, in Clathrus the receptacle arises directly from the raptured volva without the development of any stipe (Fig. 293A).

Order # 2. Lycoperdales:

The Lycoperdales include fungi which are commonly called puff-balls and earth- stars. They are chiefly saprophytes, obtaining their food from decomposing plant parts, animal remains, and other organic materials in soil. The vegetative mycelium is buried in the substratum and sends up basidiocarps on its surface.

The basidiocarps are usually more or less globose to depressed-globose, often tapering to a broad stalk-like base.

They vary greatly in size, colour, form and texture. In long diameter they may range between 2 to 3 inches and even 3 to 4 feet. Many species of puff-balls are highly edible when young, and none is known to be poisonous. A mature basidiocarp consists of a compact peridium, enclosing a mass of looser, often more or less spongy mycelial tissue, the gleba.

The gleba consists of very numerous basidia and intermingled sterile hyphae, the latter forming the capillitium (pl. capillitia).

The peridium and capillitium are superficially similar to the peridium and capillitium of the Myxomycetes, being quite different in structure and origin. The basidiospores are symmetrically attached to the sterigmata and are merely released from the sterigmata at maturity, rather than being forcibly discharged.

The glebal chambers in mature basidiocarp become transformed into a powdery mass. At maturity the peridium tends to rupture, leaving one or more openings into the gleba, especially from the top. Wind or other disturbance causes the-basidiospores to be discharged into the air, but the capillitium tends to restrict the number of spores which are discharged at any one time.

Smith (1951) subdivided the order into six families, whereas, Martin (1961) recognized only three families: Lycoperdaceae, Geastraceae and Arachniaceae.

Family Lycoperdaceae of Gasteromycetes:

The members of the Lycoperdaceae are the common puff-balls. They are characterized by the peridium of two layers, the outer opening variously and the inner remaining intact, and by the presence of capillitium in a powdery mass of spores.

Genus Lycoperdon of Gasteromycetes:

Lycoperdon, the puff-ball is a very cosmopolitan genus. It grows saprophytically on decaying organic matters in soil, often in grassland areas in forests, and even on the surface of the soil of flower pots. The basidiocarps arise either laterally or terminally on mycelial threads in which there are no clamp connections.

They may be external on the soil surface from the very beginning of development or may be shallowly subterranean when young, becoming external at maturity. The basidiocarp initial arises on rhizomorph. It is at first homogeneous throughout. Gradually the peridium is differentiated being composed of radially oriented hyphae becoming pseudoparenchymatous.

The whole interior of the basidiocarp constructed of a thick tissue gradually becomes differentiated into upper glebal area and lower sterile base (Fig. 295A & B). As the basidiocarp increases in size, cavities bounded by parallel hyphae appear in the glebal portion. These cavities ultimately develop into glebal chambers (Fig. 295C&D).

The glebal chambers may be long and narrow labyrinthine, radiating and often with twisted slits which are lined by hymenium. The sterile base may project as a columella into the glebal area. Two kinds of hvphae are formed in the glebal area when still young. The slender delicate hyphae and their branches take part of the development of hymenium.

Whereas, the stout ones make up the chief mass of glebal area. When spores begin to ripen, the elements of the hymenium become dissolved With copious effusion of water and ultimately large quantities of dry powdery spores are produced. The powdery spores are intermingled with capillitium of irregularly branched thread? arising from stout hyphae.

A mature basidiocarp has a well-marked sterile base. The basidiocarps may be globose to pyriform and with the elongation of the sterile basal portion each one may develop into a cylindrical to capitate structure possessing a definite stalk (Fig. 295A & B). The two layers of peridium are quite distinct.

The outer peridial layer the exoperidium is spiny or verrucose, and being fragile disappears entirely, especially in wet weather when the basidiocarp is mature.

It ruptures in various ways, scaling off in granules or larger pieces. The inner peridial layer, the endoparidiutn opens apically by one or more small pores (ostioles) through which the spores escape (Fig. 295E). The endoperidium, may also break up in pieces, but more often forms apical pore.

As wind or firmer objects strike the basidiocarp the spores are puffed out through one or more pores, suggesting the name puff-ball. The basidia are short, swollen and ovoid each bearing four long sterigmata on which four basidiospores are developed. The basidiospores may also be less than four (Fig. 295D).

They are globose with variously ornamented spore wall. The basidiospores fall off the basiduum, each taking a portion of its sterigma with it. The basidia eventually disintegrate.

Some Indian species of Genus Lycoperdon of Gasteromycetes:

Lycoperdon alveolatum Lev.; L. elongatum Berk.; L. microspermum Berk.; L. mundkuri Ahmad.; L perlatum Pers.

Order # 3. Nidulariales:

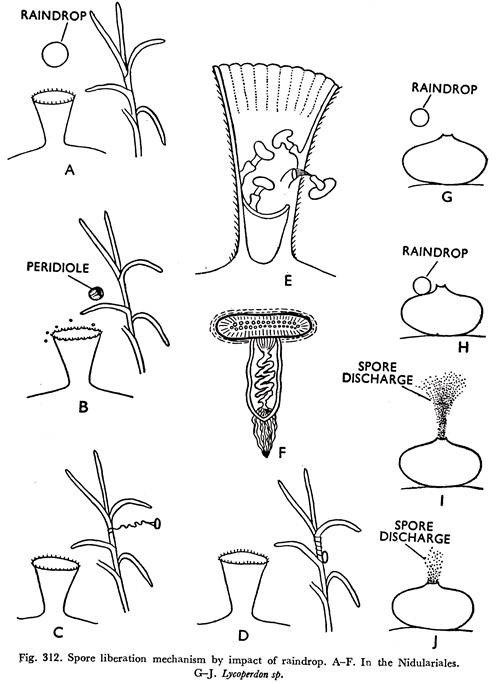

The Nidulariales are commonly known as ‘bird’s nest fungi’, also known as fungi with ‘Worchestershire Corn bell’ or ‘fairy purse’. They are so-called because in them the basidiocarp is cup-shaped and contains several tiny lenticular bodies resembling a bird’s nest with eggs. These lenticular bodies are the peridioles which are formed by the breaking of gleba.

The cup is the peridium. In this order the large basidiocarps are external, not subterranean. The Nidulariales comprise two families: the Nidulariaceae and Sphaerobolaceae. In the family Nidulariaceae several peridioles are formed in each cup-shaped basidiocarp. Whereas, in the Sphaerobolaceae the number of peridioles has been reduced to one. Here the entire gleba is transformed into a single peridiole (Fig. 308A-G).

Family Nidulariaceae of Gasteromycetes:

The members of this family are characterized by the presence of several peridioles. The epigeous basidiocarps arising from mycelial strands become differentiated into a cup-shaped peridium and numerous peridioles borne inside the cup (Fig. 296 A & B).

Each peridiole is a segment of the gleba. It becomes separated from other peridioles by hyphal gelatinization but remains attached to the inner surface of the peridium by a long stalk known as funiculus. The lenticular body of the peridiole has a thick wall—tunica which encloses basidia with basidiospores and mass of coiled and twisted hyphae.

The number of basidiospores may be four or more and may or may not be borne on sterigmata.

The peridioles are completely enclosed by the peridium and a thin membranous layer, the epiphragm which at maturity breaks exposing the peridioles. The peridioles are disseminated by splashing of raindrops. Brodie (1948-1951) working on a number of species of the Nidulariaceae has showrt that all species he worked out were tetrapolar. The principal genera are: Nidula, Nidularia, Cyathus, and Crucibulum.

Cyathus is similar to Crucibulum in many respects. But the basidiocarps of Cyathus are larger in height than those of Crucibulum. The peridium is differentiated into three layers in Cyathus, but in Crucibulum it is two-layered. The peridioles of Cyathus are dark- grey to black.

Whereas, in Crucibulum the peridioles are white. Both these two genera have basidiocarps with epiphragm and each peridiole is attached to the peridium by a funiculus.

In Nidula epiphragm is present, but the peridiole is not provided with a funiculus. Whereas, in Nidularia both epiphragm and funiculus are lacking.

Genus Cyathus of Gasteromycetes:

Both Cyathus and Crucibulum are cosmopolitan. They exhibit tetrapolar heterothallism. The genus Cyathus is rather common in bamboo groves and similar other damp shady places. The basidiocarps often arise epigeously on rotton wood as small knobs of emplacement (Fig. 296B).

Its cup-shaped peridium is differentiated into three layers: a middle pseudoparenchymatous layer lies in between the exo- and endoperidium. The exoperidium is composed of loosely woven hyphae. It bears on its surface long hairs, the setae. But the endoperidium is of more or less gelatinized -hyphae. The surface of the peridium is with striae (Fig. 296B).

The base of the cup is composed of solid mass of hyphae—the stipe (Fig. 296B). The first sign-off development of the fruit body is the appearance of brown mycelial strands at the soil surface, on which knots of hyphae differentiate. Soon develop at the periphery stout hairs with tooth like branches and brown membrane, which cover the surface of the knots as a brown felt.

Next step is the separation of the peridium from the rest of hyphae which are again separated by gelatinization into rounded portions. These are the primordia of the chambers of the gleba, or primordia of peridioles. During further growth gelatinization goes on. The apex of the young basidiocarp is at first clothed with brown hairs; as it increases in size with the general growth the hairs are pushed aside.

The summit of the basidiocarp is then covered by a thin white membrane, the epiphragm which eventually becomes gelatinized and is torn apart when the basidiocarp is mature. The originally rounded portions (the primordia of peridioles) become lenticular, whereby thick-walled, tunica is formed.

While at the flattened side of the peridiole there is a median depression (Fig. 296G). The centre of this depression is occupied by tuft of hyphae. These hyphae continue their course closely united and parallel to one another as a smooth somewhat sinuous strand, the funiculus or purse (Fig. 296G).

The funiculus expands greatly in presence of moisture producing funicular cord and the base of the funicular cord is the hapteron (p1. haptera) (Fig. 296D & E) which is quite sticky and adheres easily to solid surface. Before expansion, the funicular cord and hapteron are enclosed in bag-like structure.

Some of the hyphae of the bag-like structure form a structure, the middle piece (Fig. 296G). The middle piece again is attached to a platform of hyphae, the sheath (Fig. 296G) that is directly produced on the inner surface of the peridium (Fig. 296B).

A mature peridiole is hollow. Each peridiole is surrounded by a tunica made up of loosely intertwined hyphae and a dark thick-walled cortex, in tarn lined by a mass of very thick-walled hyaline cells (Fig. 296F). The inner part of the peridiole is made up of thin-walled hyphae between which basidia develop.

The basidia project inwards from the wall composed of thickened layer of the trama (Fig. 297A). Basidium produces 4 to 8 basidiospores. The basidiospores are not sterigmate (Fig. 297B). The basidia collapse while the spores are not yet mature or fully grown. The spores become covered by nurse hyphae arising from the inner wall of the peridiole (Fig. 296F).

They are then nourished by the nurse hyphae and increase in volume and wall thickens.

Nurse hyphae gradually disappear. Simultaneously with this, gelatinization of the tissues lining the walls of the peridiole takes place. The thick-walled mature spores remain immersed in a gelatinous matrix. The spores are freed by the decay of the peridiole wall, germinate to form mycelia. The peridioles retain viability for many years.

Both Cyathus and Crucibulum show tetrapolar heterothallism with relatively few alleles (generally not more than 15) at each locus. In Cyathus striatus sexual compatibility is governed by 2 types of sex factors Aa Bb based on different types of chromosomes and segregation.

Four types of basidiospores are developed which on germination give rise to four types of primary mycelia (Ab, AB, aB, ab). Diploidization is effected by two compatible mycelia (ABxab and AbxaB), where no factor is common.

The dissemination of basidiospores in Cyathus was not understood for many years. Martin (1927) was the first to suggest that falling raindrops can spatter the peridioles from the cup of the basidiocarp and thus eventually effect the dissemination of spores. Shea (1941) noted the hanging of peridioles from the lower surface of the leaves of some angiospermous plants.

He pointed out that the peridioles are shot into the air and become attached to whatever objects are present near the cups.

But he could not explain the exact mechanism how the peridioles are shot from the cups. Dodge (1941) reported the presence of peridioles on the upper surfaces of leaves 10 to 15 ft. above the ground and concluded that the peridioles must be discharged with considerable violence. Brodie (1951) clearly explained the mechanism of peridiole dissemination in Cyathus striatic.

According to him, raindrop is responsible for the dispersal of the peridioles and Brodie described the phenomenon as ‘splash-cup’ mechanism. Brodie observed that a large raindrop having a diameter of about 4 mm. with a velocity of about 6 metres per second falls into the basidiocarp (Fig. 292E). The raindrop creates a strong thrust upward along the inclined side of the cup and the peridioles are forcibly ejected (Fig. 292F).

When a peridiole is being splashed from a basidiocarp, the force jerks the funiculus, and the purse is torn open at its lower end where it is attached to the middle piece. The rupture of the purse causes the almost instantaneous expansion of the special mass of hyphae that had been coiled up within the lower part of the purse—the funicular cord with an attachment organ—hapteron.

The sticky hapteron at the base of the funicular cord helps to attach the peridiole to surrounding vegetation and the momemtum of the peridiole may cause the funicular cord to wrap around objects (Figs. 292G, 312G & D).

The peridiole can fly to the height of 13 to 15 ft. high in the air. If the flying peridiole with funicular cord and hapteron strikes an object, the hapteron will adhere to it (Fig. 292G) and the peridiole will dangle down and the funicular cord will tie around the object with the momentum gathered, or the peridiole may glide along the surface of a leaf.

The solid mass of hyphae around the base of the basidiocarp acts as an emplacement and prevents the cup from being knocked over by rain.

The peridioles of C. stercoreus are eaten by herbivorous animals and the basidiospores on release from the peridiole are stimulated to germinate by incubation at about body temperature. The germinated basidiospores pass out along with faeces on which mycelium is produced from which basidiocarp develops.

But whether animals play a significant role in the dispersal of peridioles of other bird’s nest fungi is uncertain.

Some Indian species of Genus Cyathus of Gasteromycetes: :

Cyathus coleusoi Berk.; C. hookeri Berk.; C. intermedius (Mont.) Tul.; C. limbatus Tul.; C. microsporus Tul.