Get the answer of: What is Fermented Fish?

The term fermented fish is applied to two groups of product, mostly confined to East and Southeast Asia: the more widely known fish/salt formulations such as fish sauces and pastes, and fish/salt/carbohydrate blends. Strictly speaking, only in the latter case is the description ‘fermented’ fully justified.

Microbial action in the production offish sauces and pastes is slight if not insignificant and the term is being used in its looser, non-microbiological, sense to apply to any process where an organic material undergoes extensive transformation.

In many areas where they are produced, fish sauces and pastes are the main flavour principle in the local cuisine and provide a valuable balanced source of amino acids. The names of some fish sauces and pastes and their countries of origin are given in Table 9.8.

Fish sauces and pastes are usually made from a variety of small fish which are packed into tanks or jars with salt usually at a ratio of around three parts fish to one part salt. This is more than sufficient to saturate the aqueous phase, to produce an aw below 0.75 and arrest the normal pattern of spoilage.

The only organisms likely to be able to grow under such conditions are anaerobic extreme halophiles. Although there have been recent reports of isolations of organisms such as the proteolytic Halo-bacterium salinarium from fish sauce, their importance remains to be established since earlier work has shown that acceptable fish sauce could be made using fish sterilized by irradiation.

The production process can take up to 18 months or more, during which the fish autolyse, largely through the action of enzymes in the gut and head of the un-eviscerated fish, to produce a brown salty liquid rich in amino acids, soluble peptides and nucleotides. Products in which autolysis is less extensive are described as fish pastes.

Authentic lactic-fermented fish products have to include as an ingredient an exogenous source of fermentable carbohydrate. Considerable variation in recipes has been noted but production is governed by two general principles: the higher the salt content of the product, the longer the production process takes but the better the product’s keeping qualities; and the higher the level of added carbohydrate, the faster the fermentation and the more acidic the flavour.

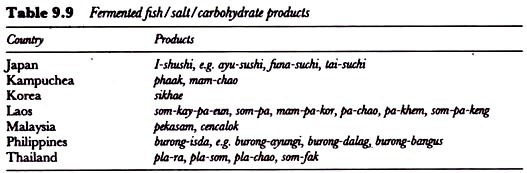

Fish/salt/carbohydrate products (Table 9.9) are generally much less popular than the fish sauces and pastes and are produced on a smaller scale. Their production also tends to be more common away from the coast and to use freshwater fish. Though superficially their production appears similar to that of fermented meat sausages, they are quite distinctive.

In products such as Burong-isda (Philippines), Pla-jao, and Pla-som (Thailand) and I-sushi Japan), cleaned fish flesh is dry salted with about 10-20% salt and left for a period of up to a day. The flesh is then usually removed from the brine that develops and may be subjected to further moisture reduction by sun-drying for a short period. Lactic fermentation is then initiated by addition of carbohydrate.

This is usually in the form of rice although traditional saccharifying agents (koji, Japan; look-pang, Thailand; ang-kak, Philippines) employing mould enzymes may be added. These accelerate the fermentation, since most LAB are not amylolytic, and also increases the .total acid produced. For example, Burong-isda containing ang-kak has a lower pH (3.0-3.9) than that produced with rice alone (4.1-4.5).

Garlic is often added along with die rice as a flavouring ingredient and this may play a similar role in directing the fermentation as spices do in fermented sausage production. The product is normally ready for consumption after about two weeks of fermentation when the microflora is dominated by yeasts and LAB which are present at levels around 107 cfu g-1 and 108 cfu g-1 respectively.

With the exception of I-sushi, these products are usually cooked before consumption and this along with the low pH generally guarantees safety. However, die small, very often domestic-scale, production can lead to extreme variations in a product’s character and failure to obtain a satisfactory rapid fermentation in I-sushi has led to outbreaks of botulism in Japan caused by C. botulinum type E.