The following points highlight the six major non-bacterial agents of foodborne illness. The agents are:- 1. Helminths and Nematodes 2. Protozoa 3. Toxigenic Algae 4. Toxigenic Fungi 5. Foodborne Viruses 6. Spongiform Encephalopathies.

Non-Bacterial Agent # 1. Helminths and Nematodes:

The flatworms and roundworms are not normally studied by microbiologists but amongst these groups there are a number of animal parasites which can be transmitted to humans via food and water.

These complex animals do not multiply in foods and they cannot be detected and enumerated by cultural methods in the way that many bacteria can. Their presence is normally detected by direct microscopic examination often following some form of concentration and staining procedure.

Platyhelminthes: Liver Flukes and Tapeworms:

In the context of foodborne parasites the two most important classes of the Platyhelminthes (flatworms) are the Trematoda, which includes the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica, and the Cestoidea which includes tapeworms of the genus Taenia. These organisms have complex life cycles which may include quite unrelated hosts at different stages.

Thus the mature stage of the liver fluke develops in humans, sheep or cattle which may be referred to as the definitive host (Figure 8.1).

It is a leaf-like animal, growing up to two and a half centimetres in length by one centimetre in width, which finally establishes itself in the bile duct after entering and feeding on the liver. Having matured, it eventually produces quite large eggs (150 x 90 µm) which have a lid, or operculum, at one end. These are secreted in the faeces after passing from the bile duct to the alimentary tract.

The eggs hatch in water to produce a highly ciliate and motile embryo (miracidium) which cannot infect the definitive host and has to infect a species, of water snail such as Limnaea truncatula.

There are several stages in this secondary host, some leading to multiplication of the parasite, but eventually the organism is released as the final larval stage (cercaria) which encyst and may survive for up to a year depending on their environment.

Cysts will only develop further if they are swallowed by an appropriate definitive host, usually cattle or sheep in which infection can cause serious economic loss, or more rarely in humans after eating raw or undercooked watercress on which the cysts have become attached.

In people the symptoms are fever, tiredness and loss of appetite with pain and discomfort in the liver region of the abdomen. The disease is known as fascioliasis and can be diagnosed by finding the eggs in the faeces or body fluids such as biliary or duodenal fluids.

Of the Cestoda, the tapeworms Taenia solium associated with pork and T. saginata associated with beef, are best known. These long, ribbon-like flatworms have humans as their definitive host but they differ in their secondary host. The larval stages of the beef tapeworm have to develop in cattle and finally infect humans through the consumption of undercooked beef.

However, the larval stages of Taenia solium can develop in humans or pigs. These larval stages, known as cysticerci, develop in a wide range of tissues including muscle tissue where they can cause a spotted appearance. The mature tapeworm of these species can only develop in the human intestine where it causes more severe symptoms in the young and those weakened by other diseases, than in healthy adults.

The effects are fairly general and may include nausea, abdominal pain, anaemia and a nervous disorder resembling epilepsy, as well as mechanical irritation of the gut.

If the latter is so severe as to cause a reversed peristalsis, so that mature segments of the tapeworm (proglottides) enter the stomach and release eggs (onchospheres), there may be an invasion of the body tissues (cysticercosis). The resulting bladder worms, or cysticerci, can especially invade the central nervous system, a situation which is often fatal.

Roundworms:

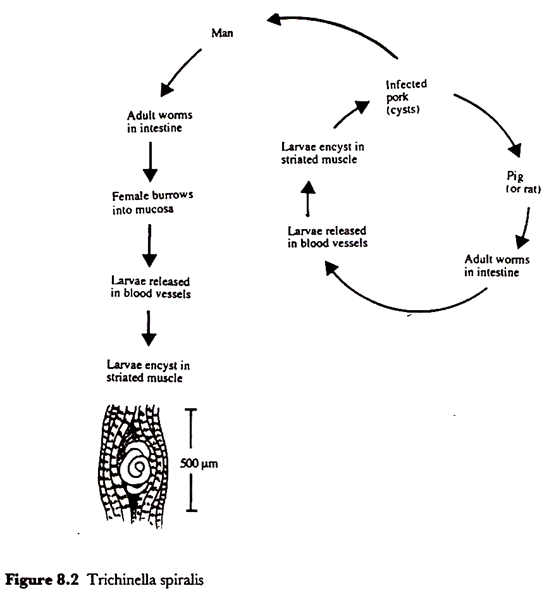

Perhaps the most notorious of the nematodes in the context of foodborne illness, and the only one which will be dealt with here, is Trichinella spiralis, the agent of trichinellosis.

This parasite has no free-living stage but is passed from host to host which can include quite a wide range of mammals including humans and pigs. Thus trichinellosis in the human population is usually acquired from the consumption of infected raw or poorly cooked pork products.

Trichinella has an intriguing life history for it is the active larval stages which cause discomfort, fever and even death. Infection starts by the consumption of muscle tissue containing encysted larvae which have curled up in a characteristic manner in a cyst with a calcified wall (Figure 8.2).

In this state they can survive for many years in a living host but, once eaten by a second host, the larvae are released by the digestive juices of the stomach and they grow and mature in the lumen of the intestines where they may reach 3-4 mm in length.

The adult worms do not cause any apparent symptoms but a single female can produce more than a thousand larvae, each of which is about 100 µm long, and it is these larvae which burrow through the gut wall and eventually reach a number of specific muscle tissues in which they grow up to about 1 mm before curling up and encysting.

Such cysts were first shown to contain these tiny worm larvae by a first year medical student studying at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London in 1835. The student was James Paget who was renowned as a Norfolk naturalist and became an eminent surgeon. He had seen, and was puzzled by, some small hard white specks in the flesh of a cadaver used in a routine post-mortem dissection.

The symptoms caused by Trichinella spiralis occur in two phases. The period during which the larvae are invading the intestinal mucosa is associated with abdominal pain, nausea and diarrhoea.

This may occur within a few days after eating heavily infested meat or after as long as a month if only a few larval cysts are ingested. The second phase of symptoms, which include muscle pain and fever, occurs as the larvae invade and finally encyst in muscle tissue.

Prevention has to be by breaking the cycle within the pig population and by adequate cooking of pork products. The United States Department of Agriculture recommends that all parts of cooked pork products should reach at least 76.7 °C.

Freezing will destroy encysted larvae but in deep tissue it may take as long as 30 days at — 15 °C. Curing, smoking and the fermentations leading to such products as salami do all eventually lead to the death of encysted Trichinella larvae.

The control of these parasites in the human food chain is effected by careful meat inspection and the role of the professional Meat Inspector, supported by legislation is very important.

Badly infected animals may be recognized by ante-mortem inspection and removed at that stage. The presence of these parasites in animals usually gives rise to macroscopic changes in tissues and organs which can be recognized by meat inspection after slaughter.

Non-Bacterial Agent # 2. Protozoa:

Amongst the protozoa only a few genera are of special concern to the food microbiologist; the flagellate Giardia, the amoeboid Entamoeba and three sporozoid (members of the class Sporozoa which contains parasitic protozoa propagated by spores) genera Toxoplasma, Sarcotystis and Cryptosporidium. Examples are known of both enteric and systemic infections.

Giardia Lamblia:

Although usually associated with water, or transmission from person to person by poor hygiene, a number of outbreaks of the diarrhoeal disease caused by Giardia lamblia, which may also be known as G. intestinalis or Lamblia intestinalis, have been confirmed as foodborne outbreaks.

The organism survives in food and water as cysts but, although it can be cultured in the laboratory, it does not normally grow outside its host.

The infective dose may be very low and once ingested the gastric juices aid the release of the active flagellate protozoa, known as trophozoites, which are characterized by the possession of eight flagella and two nuclei (Figure 8.3). The organism is not particularly invasive and it is not clear how the symptoms of diarrhoea, abdominal cramps and nausea are caused but it is possible that a protein toxin is involved.

Giardia cysts have been found on salad vegetables such as lettuce and fruits such as strawberries and could occur on any foods which are washed with contaminated water or handled by infected persons not observing good hygienic practice.

Confirmed foodborne outbreaks have implicated home-canned salmon and noodle salad but the difficulty of demonstrating low numbers of cysts in foods may be one reason why foods are rarely directly implicated. Although the cysts are resistant to chlorination processes used in most water treatment systems, they are killed by the normal cooking procedures used in food preparation.

Entamoeba Histolytica:

Amoebic dysentery can be very widespread wherever there is poor hygiene, for it is usually transmitted by the faecal-oral route. Although outbreaks from food are also documented they are surprisingly rare. The organism is an aero tolerant anaerobe which survives in the environment in an encysted form. Indeed, a person with amoebic dysentery may pass up to fifty million cysts per day.

Although most infections remain symptomless, illness may start with the passing of mucous and bloody stools, due to ulceration of the colon, a few weeks after infection and progress to severe diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fever and vomiting.

Entamoeba histolytica infection is endemic in many poor communities in all parts of the world but there has been a steady decline in reported incidence in the United Kingdom over the past twenty years.

Sporozoid Protozoa:

Cryptosporidiosis appears to be an increasing cause of diarrhoea and, although the disease is normally self-limiting, it can become a serious infection in the immuno-compromised such as AIDS patients.

It is very uncommon for food to be directly implicated in cryptosporidiosis but this may reflect the difficulties in detecting small numbers in foods and the low infective dose required to cause disease. Indirect evidence from epidemiological studies does suggest that certain foods such as raw sausages are a risk factor.

Although it is complex, the whole life cycle of Cryptosporidium parvum can take place in a single host which may be man or a species of farm animal such as cattle or sheep. By contrast, species of Sarcocystis are obligately two-host parasites, the definitive host in which sexual reproduction of the parasite takes place being a carnivore such as cats, dogs or man, and an intermediate host such as cattle, sheep or pigs in the tissues of which the asexual cysts are formed.

Two species can infect humans; S. hominis, which infects cattle, and S. suihominis from pigs. Although symptoms are usually mild, they can include nausea and diarrhoea. Beef and pork which have been adequately cooked lose their infectivity.

In the case of Toxoplasma gondii, the definitive host is the domestic or wild cat but many vertebrate animals including humans are susceptible to infection by the oocysts shed in their faeces. Thus herbivores can become infected by eating grass and other feedstuff’s contaminated by cat faeces and, once infected, their tissues may remain infectious for life.

Although foodborne infection in man may be rare, it could occur through consumption of raw or undercooked meat, especially pork or mutton. Toxoplasmosis is usually symptomless or associated with a mild influenza-like illness in healthy humans, but infection can be serious in immuno-compromised people.

Non-Bacterial Agent # 3. Toxigenic Algae:

Although strictly speaking the term algae should now be used as a collective term for a number of photosynthetic eukaryotic phyla, for the purposes of this section the prokaryotic cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, will also be included.

A number of planktonic and benthic algae can produce very toxic compounds which may be transported to filter-feeding shellfish such as mussels and clams, or small herbivorous fish which are food for larger carnivorous fish.

As these toxins pass along a food chain they can be concentrated and it may be the large carnivorous fish which are caught for human consumption which are most toxic. In the case of shellfish, the toxins may accumulate without apparently harming the animal but with potent consequences for people or birds consuming them.

Dinoflagellate Toxins:

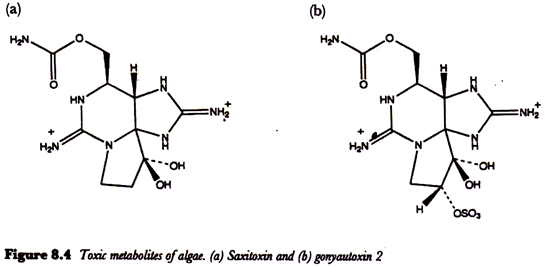

Planktonic dinoflagellates may occasionally form blooms containing high numbers of organisms when environmental conditions such as temperature, light and nutrients are appropriate. Gonyaulax catenella and G. tamarensis are the best known of a number of dinoflagellates responsible for paralytic shellfish poisoning.

This can be a serious illness with a high mortality rate. The toxic metabolites of these algae, which include saxitoxin and gonyautoxin (Figure 8.4) block nerve transmission causing symptoms such as tingling and numbness of the fingertips and lips, giddiness and staggering, incoherent speech and respiratory paralysis.

Saxitoxin, so named because it was isolated directly from the Alaskan butter clam. Saxidomas giganteus, before it was recognized that it is actually a dinoflagellate metabolite, is a very toxic compound having a lethal dose for the mouse of as little as 0.2 µg.

Recent studies have even thrown doubt on whether saxitoxin is, in fact, a dinoflagellate metabolite for it has been shown to be produced by a species of bacteria of the genus Moraxella isolated from the dinoflagellates.

To control paralytic shellfish poisoning, the collection and sale of bivalves in areas affected by algal blooms is banned. Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning is less severe and less common than paralytic shellfish poisoning and is associated with the dinoflagellate Ptychodiscus brevis (= Gymnodinium breve) one of the species responsible for the phenomenon known as a ‘red tide’.

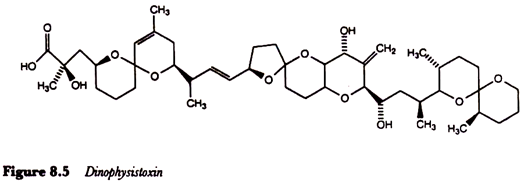

A third quite different form of poisoning associated with eating shellfish which have accumulated dinoflagellates is diarrhoeic shellfish poisoning caused by lipophilic toxins such as dinophysistoxin produced by Dinophysis fortii (Figure 8.5). The major symptoms, which usually occur within an hour or two of consuming toxic shellfish, include diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting and may persist for several days.

For many years a strange type of poisoning occurring after eating a number of different species of edible fish, including moray eel and baracuda, has been known as ciguatera poisoning. It can be a serious problem in tropical and subtropical parts of the world. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea may be accompanied by neurosensory disturbances, convulsions, muscular paralysis and even death.

For many years a strange type of poisoning occurring after eating a number of different species of edible fish, including moray eel and baracuda, has been known as ciguatera poisoning. It can be a serious problem in tropical and subtropical parts of the world. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea may be accompanied by neurosensory disturbances, convulsions, muscular paralysis and even death.

After many years research it has been shown that the toxins responsible for these symptoms, which include ciguatoxin C59H85NO19, are produced by a benthic or epiphytic species of dinoflagellate known as Gambierdiscus toxicus. The toxins are concentrated along a. food chain starting with the consumption of algae by herbivorous and detritus-feeding reef fish which themselves are consumed by the larger carnivorous fish caught for human consumption.

Cyanobacterial Toxins:

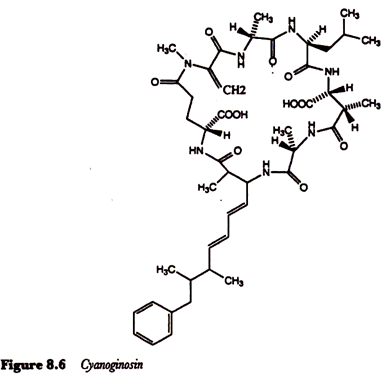

Although the blue-green algae are prokaryotes, their photosynthesis, during which oxygen is liberated from water, is characteristic of that shown by the eukaryotic algae and higher plants. Several genera of freshwater cyanobacteria, especially species of Microcystis, Anabaena and Aphanizomenon, can form extensive blooms in lakes, ponds and reservoirs and may cause deaths of animals drinking the contaminated water.

The presence of such cyanobacteria in public water supplies has also been implicated in outbreaks of human gastroenteritis. The cyanoginosins, toxic metabolites of Microcystis aeruginosa, are cyclic polypeptides containing some very unusual amino acids (Figure 8.6) and are essentially hepatotoxins.

Toxic Diatoms:

An outbreak of food poisoning following consumption of cultivated mussels from farms in Canada, which involved more than 100 cases and three deaths, was shown to be due to a glutamate antagonist in the central nervous system known as domoic acid (Figure 8.7). This compound had been produced by Nitzschia pungens, a chain-forming diatom of the phytoplankton.

Non-Bacterial Agent # 4. Toxigenic Fungi:

The fungi are heterotrophic and feed by absorption of soluble nutrients and although many fungi can metabolize complex insoluble materials, such as lignocellulose, these materials have to be degraded by the secretion of appropriate enzymes outside the wall. A number of fungi are parasitic on both animals, plants and other fungi, and some of these parasitic associations have become very complex and even obligate.

However, it is the ability of some moulds to produce toxic metabolites, known as mycotoxins, in foods and their association with a range of human diseases, from gastroenteric conditions to cancer, which concerns us here.

The filamentous fungi grow over and through their substrate by processes of hyphal tip extension, branching and anastomosis leading to the production of an extensive mycelium. Some species have been especially successful in growing at relatively low water activities which allows them to colonize commodities, such as cereals, which should otherwise be too dry for the growth of micro-organisms.

Frequently, when moulds attack foods they do not cause the kind of putrefactive breakdown associated with some bacteria and the foods may be eaten despite being mouldy and perhaps contaminated with mycotoxins.

Indeed, some of the changes brought about by the growth of certain fungi on a food may be organoleptically desirable leading to the manufacture of products such as mould-ripened cheeses and mould-ripened sausages.

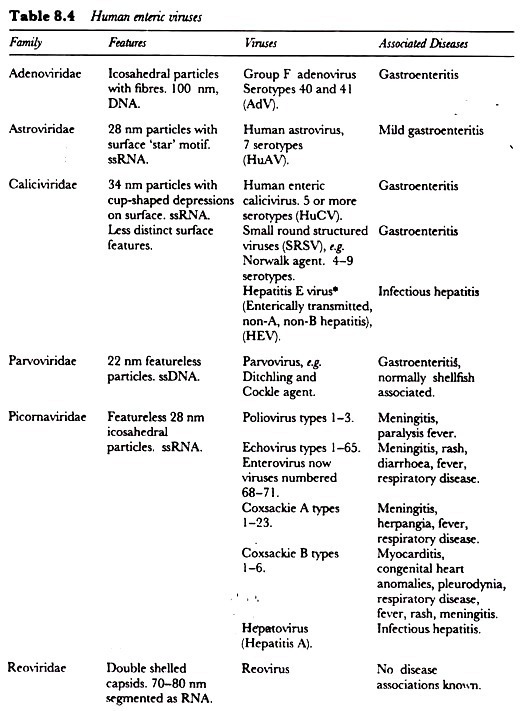

Non-Bacterial Agent # 5. Foodborne Viruses:

Viruses differ profoundly from other types of micro-organism. They have no cellular structure and possess only one type of nucleic acid (either RNA or DNA) wrapped in a protein coat or capsid. They are also extremely small, with diameters in the range 25-300 nm (1 nm = 10-3µm), so that most are invisible using conventional light microscopy and can only be viewed with the electron microscope.

Some viruses (for example HIV) are enveloped by an outer lipid membrane, but these cannot be transmitted via food since they are relatively fragile and are destroyed by exposure to bile and acidity in the digestive tract.

As obligate intracellular parasites, viruses cannot multiply other than in a susceptible host cell whose machinery and metabolism they hijack for the purpose of

viral replication. Consequently, virus multiplication will not occur in foods which can act only as a passive vehicle in the transmission of infection.

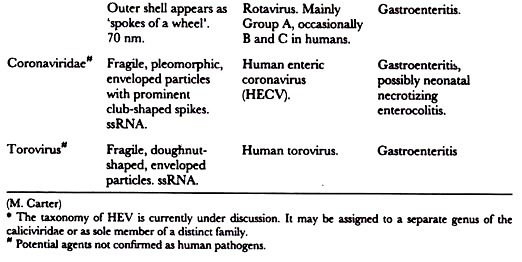

In recent years viruses have been increasingly recognized as an important cause of foodborne illness. There are currently more than 100 human enteric viruses recognized (Table 8.4), and since these are spread by the faecal-oral route, food is one potential route for transmission.

Non-Bacterial Agent # 6. Spongiform Encephalopathies:

Spongiform encephalopathies (SEs) are degenerative disorders of the brain that occur in a number of species. They are recognized by the clinical appearance of the affected animal and the characteristic histological changes they produce in the brain. Microscopic examination reveals the presence of vacuoles in the neurons giving the grey matter the appearance of a section through a sponge.

Scrapie, the disease of sheep and goats, has been known since the 18th Century but was first described scientifically in 1913. Its name is derived from one of the symptoms; an itching which causes the infected animal to scrape itself against objects.

The agent of scrapie and other SEs have been described as ‘slow viruses’ due to their long incubation periods. However it is known that the infectious agent, known as a prion, is neither a bacterium nor a virus. It is invisible in the electron microscope, cannot be cultured in media or cell cultures, does not provoke the formation of specific antibodies in infected animals and cannot be detected serologically.

It is also very resistant to heat, irradiation and chemical treatments such as formalin. In sheep, the illness is transmitted both vertically and horizontally and other animals have been infected as a result of intra-peritoneal or intra-cerebral injection of infected tissue preparations.

Three human SEs are known, Gerstmann-Straussler syndrome, Creutzfeldt- Jacob disease and kuru, though the last two may in fact be the same disease. Kuru, first described in 1957, is restricted to the Fore people of Papua New Guinea where it was the major cause of death among Fore women.

It was shown to be transmissible to chimpanzees by intra-cerebral inoculation with brain extracts from dead patients and it was eventually decided that human transmission was in fact foodborne, albeit of a rather special kind.

The Fore tribe have a tradition of cannibalism and it was the tribal custom for women and children to eat the brains of the dead as a mark of respect. Since this practice was suppressed in the late fifties incidence of the disease has declined.

Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease is more widespread than kuru and in the UK has an incidence of 1 per 2 000 000 inhabitants. Accidental transmission by injection of contaminated pituitary extracts, corneal grafting and implantation of contaminated electrodes has occurred but oral transmission has not been described.

Much attention has been focused on these conditions since the emergence of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle in Britain in 1985/6. The illness is thought to result from the scrapie agent crossing the species barrier and being transmitted to cattle by scrapie-infected sheep protein fed to cattle.

Its emergence at this time has been linked with changes in the commercial rendering processes used in the production of animal proteins such as reduced processing temperatures and abandonment of the use of solvents to extract tallow.

Control measures introduced in the UK include prohibition of the sale of bovine offal from animals more than six months old and banning the feeding of ruminant-derived protein to ruminants.

The concern is that if the agent can cross the species barrier and be acquired through food, it could do so again – infecting humans. However the consensus of expert opinion is that this is highly unlikely. There is no evidence linking human occupational exposure to potentially scrapie-infected tissues with degenerative encephalopathy, and sheep and sheep products have been eaten for longer than scrapie has been known without any evidence of it causing a similar human illness.

The evidence available suggests that these illnesses are intoxications rather than infections. The prion contains a protein PrPSc which is also a major component of the plaques formed in the brains of affected individuals. PrPSc is a modified version of the protein PrPc found normally on the outer surface of neurons.

It is thought that prion PrPSc finds its way to the neuron surface where its interaction with PrPC leads to production of further PrPSc. This initiates a chain reaction, the accumulation of PrPSc, plaque formation, and the onset of neurological symptoms.