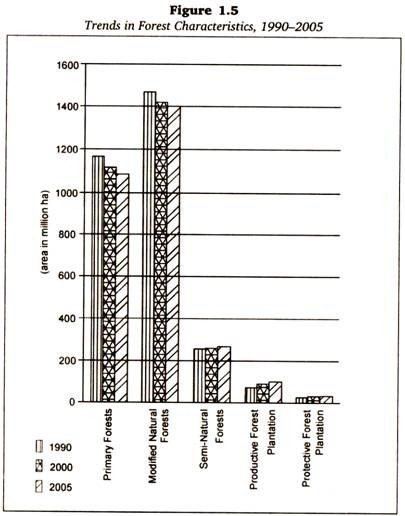

A mature forest acts as a reservoir, holding large volumes of carbon even if it is not experiencing net growth.

Forest management can thus have an influence on carbon sequestration. Present estimates indicate that with appropriate policies the carbon pool in the terrestrial system could increase by up to 100 Gtc (Gigatones of Carbon) by the year 2050 compared to the level of carbon that would be sequestered without such policies (IPCC, 2001).

This is equivalent to about 10 to 20 per cent of projected Greenhouse Gases emissions from fossil fuel consumption during the same period.

Reducing deforestation, expanding forest cover, expanding forest biomass per unit area, and expanding the inventory of long-lived wood products are some of the activities that could help global community realizing the carbon sequestration potential of forest ecosystem.

The modification of atmospheric environment by land use of cities is the most apparent anthropogenic activity that impacts on city’s microclimate. The city’s land use pattern destroys existing microclimate and creates great complexity. With the onset of the industrialization era, the trend towards urbanization accelerated leading to significant changes in the climate in and around the most mega-cities (Singh, 2006).

Forest ecosystem has potential to capture and retain large volumes of carbon over long periods as trees absorb carbon through photosynthesis process. A young forest, when growing rapidly, can sequester relatively large volumes of additional carbon roughly proportional to the forests growth in biomass.

The Study Region:

The urban population of Delhi, which was only 0.21 million in 1901, has increased by about 60 times to 12.82 million in 2001. Population density of Delhi was 9,294 people per km2 in 2001. The capital of India attracts a growing population and about 93 per cent of Delhi’s population lives in urban part. The present migration rate is more than 1.6 lakh persons per annum. In 1991, Delhi’s total 1483 km2 area, out of it 46.2 per cent was urban settlement, with only 53.79 per cent remaining in rural areas, as compared to 39.9 per cent and 60.1 per cent, respectively in 1981. At present National Capital Territory (NCT) Delhi has 60 per cent urban and 40 per cent rural area (2001).

Delhi with 28 industrial areas is a major centre for the whole of North India, with wholesale markets for nine different types of goods including fruits and vegetables, automotive parts, textiles etc. The total number of industries in Delhi was about 8,160 in the year 1951, which steeply increased to 1,29,363 by 1998 (approximately 18 times) while the employment in industry grew from 16.94 per cent in 1951 to 32.43 per cent in 1991 (ibid.).

Urban Development and Carbon Emission:

The rapid growth of urbanization and industrialization inevitably led to higher consumption of energy usually reflected in increasing pollutant emission. The main sources to atmospheric gases and matters are due to burning of fossil fuels to generate heat and power.

In the Indian urban cities, atmosphere constantly receives inputs from anthropogenic activities sources. Among the anthropogenic sources are pollutants from domestic heating and lighting, transport automobiles, railway, industrial activities, and incineration of municipal and industrial and domestic wastes. Some of these may also constitute fine particles from fossil fuel like coal.

In Delhi and Mumbai, the major sources of atmospheric pollution are the vehicular source followed by industry and domestic sources (Figure 1), while in Kolkata major emission sources are industry and power generation plants. In these cities, the industrial activity is a major source of SO2 and SPM emission whereas vehicular and domestic are the main source of CO2 emission in the city’s atmosphere (Kumar and Singh, 2003).

The major gaseous pollutants include sulphur dioxide (SO2), oxides of nitrogen (NOx), and carbon dioxide (CO2). The suspended particulate matter (SPM) levels were observed to be much above the permissible levels at all the monitoring stations. The vehicular and industrial sectors are the major sources of oxides of nitrogen.

The major anthropogenic sources of SO2 in the atmosphere are burning of fossil fuels for industrial and domestic purposes. For CO2, emissions taken into account for the release are 15.9 million tonnes. These emissions can rise to 32.6 million tonnes if the present state of development continues without any major emission mitigation efforts.

Sources of Pollution:

Delhi faces air pollution problems due to three major sources: transport, domestic, and industrial sectors. Vehicle population has increased from 2.4 million in 1993-94 to 4.2 million in 2003-04. Thus, an increase of about 87 per cent has been registered in a period of 10 years (Government of NCT of Delhi).

Delhi has experienced an exponential growth in the number of personalized vehicles over the last two decades. Petrol driven vehicles account for more than 81 per cent of the pollution, whereas diesel vehicles account for only 19 per cent of the total pollution of the city.

The other two major sources of Delhi’s air pollution loads are fuel combustion in industrial activities and domestic stoves. Among the large-scale industries, thermal power plants are the most prominent contributors to air pollution. Alone they are responsible for the release of about 302 tonnes of pollutants per day.

They were responsible for as much as 10 per cent (approx.) of the air pollution load in 2001. Although the concentration of carbon monoxide had a gradual decline from 4,183 mg/m3 in 2,001 to 3,258 mg/m3 in 2002, still it continues to be above the danger mark of 2,000 mg/m3.

According to Figure 2, emissions from the industrial sector have gone down from 56 per cent in 1970-71 to 40 per cent in 1980-81 and 29 per cent in 1990-91. It has been projected to further decrease to 20 per cent in 2000-01. The emission load from vehicular sources also shows a clear increase.

Presently 1, 68,000 metric tonnes of pollutants are being emitted. This is about 50 per cent more than 87,000 metric tonnes emitted in 1987. In the last eight years, emission of carbon monoxide has gone up by 120 times, hydrocarbons by 204 times, sulphur dioxide by 5.8 per cent, oxides of nitrogen by 45 times and lead particles by 100 times (Malik, 1997). Every day 1,220 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide, 570 tonnes of hydrocarbons, 330 metric tonnes of nitrogen oxide and 253 metric tonnes of sulphur dioxide are released in Delhi’s air.

Though every Delhite breathes nearly 16.5 kg of air loaded with vehicular emissions, the auto, bus and truck drivers get maximum exposure to the vehicular pollution due to their long hours (14-18 hours) of driving (ibid.).

Suspended particulate matter at all stations is far higher than the annual average concentration (Central Pollution Control Board standard for residential and industrial areas is 140 mg/m3). The annual NOx concentrations at all the stations are within Central Pollution Control Board standards. The standard for residential areas is 60 mg/m2. The annual concentration of SO2 at all stations is well within the Central Pollution Control Board standard for residential and industrial areas (60 mg/m3) (Figure 3).

As such SO2 level has decreased by 53.39 per cent in 2003 as compared to 1998 (i.e., year of CNG initiative). This shows tremendous achievement after conversion of all buses/taxis/autos in CNG mode. Annual average value of NO2 has decreased significantly (4.82 per cent) in 2003 as compared to previous year. It was 45mg/m3 in 2003 as against 47.28 mg/m3 2002.

Thus ambient air quality has improved significantly which can be gauged from the fact that as compared to 1997 the concentration of carbon monoxide has fallen by 41.14 per cent. Sulphur dioxide level has reduced by 49.20 per cent. However, not much change was observed in case of NO2. There was tremendous improvement in concentration of particulate matters (SPM and RSPM) in the ambient air in 2003 as compared to 2002 (Table 1).

Major Driving Forces Population Growth:

Promoted to capital of British India in 1911, Delhi became the capital of independent India in 1947. After 1947, Delhi had to accommodate 4, 70,000 refugees from west Punjab and Sindh, while 3, 20,000 Muslims left the city for Pakistan (Guilmoto and Vaguet, 2000). Delhi has experienced the highest demographic growth in the last few decades. Being the administrative capital, it attracts people from all over India for political, economic, social reasons.

According to Guilmoto and Vaguet, since 1961, Delhi has been the third largest Indian metropolis, behind Mumbai and Kolkata. Delhi has experienced the highest demographic growth of the last decades: 5.1 per cent annually from 1951 to 1961, 4.5 to 4.6 from 1961 to 1981, and 3.9 per cent annually from 1981 to 1991. Its population increased from 1.4 million in 1951 to 8.4 million in 1991, and 13.78 million inhabitants in 2001 (Figure 4).

Industrialization in Delhi:

Out of a total of 1, 26,000 industries, there are 98,000 industries in non-conforming areas as per the Master Plan of Delhi, 2001 (Figure 5). The Supreme Court has directed a number of polluting industries in Delhi to close down and ordered certain categories of industries to shift from non-conforming to conforming areas. In July 1996, closure and shifting of 168 industrial units took place in Delhi. In September 2000, 27 ‘polluting’ types of industries were shut down. Industries were shifted to outskirt villages of Narela and Bawana.

Developmental Activities:

The Metro Rail Transit System has been a very well planned network from Rithala to Shahdara. The trees cut and transplanted for the construction of the metro corridor at the various locations in the north and central Delhi has tremendously changed the scenario of Delhi. Total, 3,548 trees were cut and against these only 1,749 trees were planted.

Thereby making a total deficit of 1,799 (Delhi Metro Rail Corporation, 2003). More trees have been cut than the trees planted. The plantations have been done in areas where it is not required. It should have been planted at the locations of the construction of the Metro and Rail corridors where it is urgently required as the existing trees have been cut leading to the locations becoming prone to the environmental degradation in form of pollution etc. This is a case of faulty implementation.

Forest as an Instrument of Carbon Sequestration:

The Ridge forest in Delhi is one of the world’s largest city forests and this natural vegetation of Delhi is botanically described as a ‘Scrub forest’ (Singh, 2002). In 2003, Delhi’s total forest and tree cover constituted about 268 sq km, which is about 18.07 per cent of the state’s geographic area (Forest Survey of India, 2003) (Table 2). This is a remarkable increase in the forest cover from 15 sq. km in 1987 to 170 sq. km in 2003.

Role of Vegetation:

Plants have been seen to play an important role in both reducing the environmental pollution load as well as serve as pollution indicators without sustaining damage or retardation. It acts as an effective carbon sink and natural air conditioner lowering temperatures. Trees reduce thermal pollution by checking heat buildup in the atmosphere by preventing the radiation of heat from base surfaces.

Vegetation cover acts as a pollution scavenger or pollution sink, as it absorbs gases and gathers particulate matter through leaves having large surface areas. The green and leafy portion of the trees and plants has the capacity to filter dust, smoke and other pollutants in the air. Some species like Ficus, Mangifera, etc., also act as good dust collectors.

One hectare of woodland (1,000 trees) absorbs as much as 3.7 tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere and gives out 2.5 tonnes of life sustaining oxygen. Studies show over a distance of 200 sq m or less, a green cover can reduce the concentration of pollutants by 120gm/cubic metre. A full-grown Peepal (Ficus religiosa) tree is, for instance, estimated to give out 600 kg of oxygen in 24 hours. Herein lies the importance of the 151 sq. km of forest and tree cover in Delhi, though this constitutes 10.2 per cent of the Delhi’s geographical area of 1,483 sq. km.

According to the Vatavaran report, when a patch of wilderness is converted to a park the following changes are noticed:

i. Temperature goes by 2-4°C.

ii. Noise level goes up by 40-50 decibels.

iii. 1 sq km of forest releases 3 tonnes of oxygen whereas a park of same size releases one tonne of oxygen. Oxygen generation goes down.

iv. 1 sq km of forest absorbs 4.2 tonnes of carbon dioxide whereas a park absorbs 1.7 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Absorption of carbon dioxide goes down.

v. Dust absorption capacity goes down. A 10 sq m forest area can absorb 11 gms of dust in 24 hours whereas a park of same size at the same time absorbs 6 gms of dust.

There is a great need to identify tree and plant species that can withstand and combat the pollution of the city effectively. For instance, it was found that Jamun (Eugenia jamboland), was the most suitable to plant along roadsides as it was the least affected by lead exhaust.

Tall plants are less susceptible to pollutants as revealed from more than the 90 per cent survival percentage of plantation along Shahdara Link drain running parallel to a road from Delhi-Uttar Pradesh border (Report, TCPO, 2003). Along the air pollution tolerant tree species, those suitable for Delhi are Peepal (Ficus religiosa), Siris (Albizzia lebbek), Amaltas (Cassia Fistula), Ber (Zizyphus jujuba), Neem (Azadirachta indica), Imli (Tamarindus indica), Shisham (Dalbergia sisso), Dhak (Butea monospermd), Gular (Ficus glomerata), Pilkhan (Ficus infectoria), Sataun (Alstonia Scholaris), Desi kikar (Acacia nilotica).

Species suitable for area where gaseous pollutants are dominant are—Desi Kikar (Acacia nilotica), Bel (Aegle marmelos), Ulloo Neem (Ailanthus excelsa), Siris (Albizzia lebbek), Sataun (Alstonia Scholaris), Neem (Azadirachta indica), hisham (Dalbergia sisso), Peepal (Ficus religiosa), Pilkhan (Ficus infectoria), Lagerstromia flosreginae, Maulsiri (Mimusops elengi), Kaner (Nerium indicuni) (Greening Delhi Action Plan, 2001).

Species suitable for abatement of noise and dust pollution are—Neem (Azadirachta indica), Amaltas (Cassia Fistula), Peepal (Ficus religiosa), Pilkhan (Ficus infectoria), Maulsiri (Mimusops elengi}, Gular (Ficus glomerata), Arjun (jerminalia arjuna), Kigelia pinnata, Jamun (syzygium cumini), Bauhinia variegata, Semul (Bombax ceibd). Cassia nodusa, Cassia javanica, facaranda mimosaefolia.

Afforestation as Carbon Mitigation Measures:

The forestry sector provides a number of carbon sequestration options such as increasing number of ‘green belts’ of pollutant resistant trees and shrubs. One hectare of woodland absorbs 3.7 tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and gives out 2.5 tonnes of oxygen.

Herein lies the importance of the 151 sq km of forest and tree cover in Delhi, though this constitutes 10.2 per cent of the total geographical area of 1,483 sq km. The current rate of afforestation in Delhi is about 1.1 per cent, which has only marginal carbon sequestration potential. In Delhi, various afforestation programmes has been started by different governmental and non-governmental organizations along with the efforts taken by its citizens.

According to one such programme started by the Government of India in 2003-04, the various Residents Welfare Associations, particularly those who are associated with the Bhagidari Programme (a programme started by the state government in 1999 to involve people of Delhi in improving the social and environmental situation of Delhi) will act as the basic co-coordinating unit in the programme.

Their work will include—informing the residents about the programme, gathering volunteers for planting, identifying places for planting, assessing seedling requirement, identify types of species desired, identify nursery from where desired seedling will be procured, planning labour input for digging the pits, coordinating with the non-government organization and government agencies and chalking out programme of plantation in their respective colonies so that planting can be done by government agencies in association with Resident Welfare Association (Greening Delhi Action Plan, 2003).

Several organizations such as environmental groups, educational groups. Rotary Clubs, Lions Club, governmental organizations like Municipal Corporation of Delhi, Central Public Works Department, Department of Horticulture, Government of Delhi, Public Works Department (Horticulture), New Delhi Municipal Committee, Delhi Development Authority etc., will be identified and involved closely in the programme as motivators and for conducting nodal activities. Their work will include: coordination with Resident Welfare Associations and other bodies like market associations for plantation activities, guiding people to plant trees properly.

The corporate sector can play decisive role in the programme by sponsoring and arranging logistic and other requirements. This can include sponsorship of advertisements for awareness; provide vehicles for transportation of seedling; provide tree guards for the plants. Besides, various corporate bodies can adopt schools for planting and other environment improvement programmes.

The forest department would coordinate the programme at various levels. It will decide upon distribution points for free distribution of saplings as also the species to be distributed for planting. The involved stakeholders have already started contributing towards the goals of the programme by distributing more than 3 lakh saplings free of cost.