In this article we will discuss about the anatomy of human heart with the help of suitable diagrams.

The human heart is roughly heart-shaped structure and rests obliquely in the thoracic cavity (Fig. 7.3). The anterior surface of the human heart faces the sternum, the posterior surface—the base of the cone faces the vertebral column and the inferior or diaphragmatic surface rests on the diaphragm.

The human heart has got four chambers (Fig. 7.4); two ventricles and two atria—both right and left. The two left chambers are separated from the two right ones, by a continuous partition, the artial portion of which is called the interatrial septum (fibrous) while the ventricular part is known as the interventricular septum (upper one-fourth fibrous, lower three-fourths muscular). From the left ventricle arises the aorta, carrying oxygenated blood to the tissues.

From the right ventricle, which is less muscular than the left, arises the pulmonary trunk, carrying reduced blood to the lungs. The right atrium receives all the venous blood from the body through three veins; the inferior and the superior venae cavae, and the coronary sinus. The left atrium receives all the oxygenated blood from the lungs through pulmonary veins.

Thus the four chambers of human heart perform four different functions. The course of circulation is as follows (Figs 7.1 & 7.2). The left ventricle propels oxygenated blood to the tissues. Here, it gives up oxygen and becomes reduced. The reduced blood comes back to the heart through the veins and is received by the right atrium. From the right atrium it passes into the right ventricle, which then propels it into the lungs.

Here, it becomes re-oxygenated, and is returned to the left atrium through the pulmonary veins. From here it enters the left ventricle and is pumped out into the greater circulation again. In this way circulation goes on. The systemic circulation, therefore, begins in the left ventricle and ends in the right atrium.

The pulmonary circulation starts in the right ventricle and ends in the left atrium (Fig. 7.2). The right half of the heart is concerned with reduced blood, while the left half with oxygenated blood. Two technical terms are used in connection with heart, e.g., systole and diastole. The term systole means contraction and diastole means relaxation.

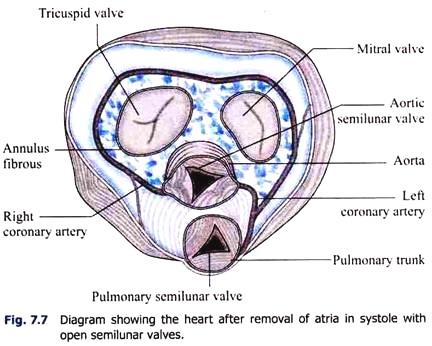

Valves of the Heart (Figs 7.4 & 7.5):

There should not be any admixture between arterial and venous blood. In other words, circulation must be strictly one way. This is done by the action of valves. There are four sets of valves in the heart.

The right atrioventricular opening is guarded by tricuspid valve [anterior (infundibular), posterior (marginal) and medial (septal) cusps], the left opening by the mitral (due to its resemblance to a bishop’s mitre) or bicuspid valve [anterior (aortic) and posterior cusps]. The openings of the aorta and pulmonary artery are guarded by semilunar valves (three cusps).

The cusps of tricuspid valve and mitral valve are triangular in shape and are attached at their bases to margins of fibrous connective tissue encircling the atrio-ventricular orifices. These valves open when the blood passes from the atria to the ventricles. The apices of the valves are projected within the ventricles during flowing of blood into ventricles. But the apices are restricted to bulge within the atrium during ventricular contraction by the presence of chordae tendineae which attach the apical end of the valve and the papillary muscle in the ventricular wall at the other (Fig. 7.6).

During ventricular contraction the pressure of blood forces the cusps into apposition and closes the orifice and the chrodae tendineae prevent the cusp to go inside the atria or allowing blood to be ejected back into the atria. During the contraction of ventricular walls, the papillary muscles contract simultaneously and do not assist to close the valves.

These muscles also pull vanes of the valves inwards towards the ventricles to prevent excessive backward bulging of the valves towards the atria. If one of the papillary muscles is paralysed or if a chorda tendinea is ruptured under certain abnormal conditions (i.e., ischaemia), the valves bulge far backwards.

The larger and stronger aortic semilunar valve [right (anterior), left and posterior (right) cusps] guards the orifice between the left ventricle and the systemic aorta, whereas the pulmonary (pulmonic) semilunar valve [anterior (left), right and left (posterior) cusps] guards the opening between the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk.

Thicker nodules or corpora Arantii are attached at the centre of free margin of each semilunar pocket. Sinuses of Valsalva or aortic sinuses are present between aortic wall and cusps of the valve (Fig. 7.5). During ventricular contraction the intraventricular pressure rises and the push opens the valves. During ventricular relaxation the blood begins to flow back and the cusps are thus kept in apposition and the orifice is closed (Fig. 7.7).

Action of the Valves:

The atrioventricular (A.V.) valves open towards the ventricles and close towards the atria. The semilunar (S.L.) valves open away from the ventricles and close towards the ventricles. So that when atria contract, atrioventricular valves open and blood passes into the ventricles (Fig. 7.8).

When ventricles contract, atrioventricular valves close, but semilunar valves open. This prevents regurgitation of blood into the atria but allows it to flow out of the ventricles (Fig. 7.9). In this way circulation becomes one way.

Heart is a miracle of constants. The two ventricles contract simultaneously, as also the two atria. The same amount of blood passes out of the ventricles at the same time during systole. The same amount of blood enters the heart at the same time during diastole. Any discrepancy in the time or in the quantitative relations may ultimately cause heart failure.