It has been mentioned earlier that there have been significant changes in various elements of environment, i.e., biotic and abiotic in the last century, which are usually attributed to anthropogenic activities.

Some of the changes such as biodiversity loss, land use/cover changes and forest loss have been largely due to human activities.

However, the underlying causes for climatic changes are still not clearly understood. Scientists, generally, describe many anthropogenic activities such as forest loss and emission of carbon gases as basic causes of climatic change.

Nevertheless, these changes cannot be and should not be directly attributed to anthropogenic activities, in view of the fact that climate has ever been changing since the earth originated.

Climate change was in process even when human was in primitive stage. Thus, it can be said that climate change is a natural process and is not derived by anthropogenic activities solely. However, anthropogenic activities, certainly, have given pace to climate change. Some of the vital examples of environmental changes, which are human-induced and human-accelerated in recent past, can be traced in India. Introduction of railways during pre-independence period was probably the first major assault on India’s forests and biodiversity.

Establishment of railway tracks claimed huge amount of wood, which resulted in huge loss of forests and biodiversity in Himalayan region during pre-independence period. It resulted in the forest and biodiversity loss largely in Shivalik Himalayan region, Central Indian upland and South India. A few species, which were suitable for construction of railway tracks, were lopped.

It changed the composition of tree species in many regions and eventually the quality of habitat due to which many faunal species were threatened. Shivalik region of Himalaya has been conducive for the reptiles and insect species due to its climatic conditions. Many reptile species became extinct in the region due to deforestation during the same period.

Indo-China war of 1962 can be traced as another bench-mark in the history of environmental changes in the whole of Himalayan region. India’s defeat in war led to the introduction of gigantic network of roads deep into the hills of Himalaya, which claimed huge deforestation and biodiversity loss in almost every corner of Himalaya.

Introduction of a large number of hydroelectricity projects in recent past have also been responsible for environmental change or the so-called degradation in Himalayan region. Uttarakhand state, which lies in the Himalaya, is no exception in this context. Uttarakhand has also experienced similar changes in recent past.

Loss of natural forests and biodiversity has become common phenomena in state. Plantation of non-native species can be seen very often, which change the specie composition in the region. Non-native species compete for the space and replace native species. Thus, it is also a grave environmental problem in Uttarakhand.

Wildlife has experienced severe modifications. Some of the wild and traditional domestic species, due to changes in socio-economic life of people and resulted land use/cover changes, have reduced significantly. Tiger, leopard, snow leopard, black bear, brown bear and musk deer, etc., have undergone significant reductions in the state (Jhala et al., 2008 and Jhonsingh and Negi, 2003).

Similarly, many traditional domestic species such as sheep, goat, cow, etc., are now considered endangered in Uttarakhand. Yak has reached the stage of complete extinction. Agricultural land has increased, pastures have degraded (Rao, 2001), increasing extreme events have led to increased waste land and almost all the glaciers have been retreating.

All kind of extreme events have been reported to increase in Uttarakhand. Summer season has become even warmer. Temperature of summer and winters has increased marginally. High altitude regions, e.g., Joshimath (Chamoli) and Gangotri (Uttarkashi), which never had fans and refrigerators, are now having such machines.

This is a clear indicator of climatic change (Suraj Mai, 2006). Duration of winter season has reduced significantly. Average temperature of February has increased (Singh and Yadav, 2000). Duration of monsoon season has reduced significantly.

However, the amount of precipitation has been observed to increase slightly. Regions are now receiving precipitation in very short durations that has resulted in extreme precipitation. Altitudinal shift of snowfall and rainfall can also be observed in high altitude regions.

The areas of snowfall and rainfall have shifted upward. In almost all the regions, the rainfall has taken over the regions of snowfall. The intensity of landslides, avalanches and rock fall; all have increased in Uttarakhand due to combination of anthropogenic and natural factors.

Status of Forests and Biodiversity in Uttarakhand:

Uttarakhand is a hill state. Thus, about 66 per cent of the total geographical area of the state is required to be under forest cover to keep the ecosystem functioning properly. FSI (2005) reveals that forest cover accounts for about 24,442 sq km, which is 45.70 per cent of total geographical area of Uttarakhand.

Thus, it can be said Uttarakhand is far from healthy ecosystem and forest cover. Improvement of forest cover on additional 20 per cent geographical area is needed to achieve the threshold of healthy ecosystem, i.e., 66 per cent forest cover in a hill state. Although, it seems far from reach in the near future, since forest cover shows a stagnant improvement in Uttarakhand in the recent past.

In 1997, an area of 23,243 sq km was under forest cover, which was 43.46 per cent of total geographical area of Uttarakhand. It marginally increased to 24,460 sq km (45.73%) during 1997-2003 and it declined marginally (18 sq km) during 2003-05 (FSI, 2005). Loss of forest cover during the said, period can be attributed to rehabilitation of Gujjars, Tehri dam oustees and rotational felling of eucalyptus in Haridwar districts.

Nainital and Udhamsingh Nagar are also facing the similar trend. Forest cover of Uttarakhand, when compared with India showed similar trend. Forest cover of India in 1997 was about 6, 33,397 sq km (19.27%), which increased up to 6, 77,816 sq km (20.62%) during 1997-2003. Subsequently, it showed a marginal decline of about 728 sq km (0.02%) during 2003-05 (Figure 2.1). The study reveals that about 7.5 per cent of the geographical area of Uttarakhand is under Very Dense Forests (VDF), 27 per cent under Moderate Dense Forests (MDF) and 11.3 per cent is under Open Forests (OF), which are about 16 per cent, 59 per cent and 25 per cent of total forest cover of Uttarakhand respectively (Table 2.1).

The study reveals that about 7.5 per cent of the geographical area of Uttarakhand is under Very Dense Forests (VDF), 27 per cent under Moderate Dense Forests (MDF) and 11.3 per cent is under Open Forests (OF), which are about 16 per cent, 59 per cent and 25 per cent of total forest cover of Uttarakhand respectively (Table 2.1). Also, tree cover mapping has been done in previous two reports, i.e., 2003 and 2005, which is the endowment of technical advancement of satellite images. Tree cover accounts for about 2 per cent of total geographical area of the state, bringing forests and tree cover to a total of 46.93 per cent.

Also, tree cover mapping has been done in previous two reports, i.e., 2003 and 2005, which is the endowment of technical advancement of satellite images. Tree cover accounts for about 2 per cent of total geographical area of the state, bringing forests and tree cover to a total of 46.93 per cent.

There has been no change in VDF during 2003-05, while MDF decreased by about 13 sq km and OF by 5 sq km While, VDF in India account for 1.67 per cent, MDF for 10.12 per cent, OF for 8.8 per cent and tree cover 2.8 per cent. Thus, Uttarakhand has more area under forests when compared with national average.

Analysis of the present forest cover of Uttarakhand at district level reveals that all the districts have more proportion of forest cover with respect to their geographical area than national average (20.6%). Proportion of forest cover in different districts can be well explained and associated with degree of exposure of districts to human activities and environmental conditions.

Districts, which are located in Shivalik Himalaya and at the junction of Shivalik and middle Himalaya; such as Haridwar, Udhamsingh Nagar and Dehradun have fewer forests as 26.7 per cent, 22.2 per cent and 51.6 per cent respectively when compared with other districts. These districts are densely populated and have been facing intense pressure from anthropogenic activities.

Therefore, forest cover of these districts has been reduced significantly. While, on the other end, a large area of districts of Uttarkashi, Chamoli and Pithoragarh is well above the tree-line and do not support growth of trees and forests. A large area of these districts is under glaciers. Thus, environmental conditions are little harsh for the forest growth. Also, these districts are in the great Himalaya, therefore only little human population and resulted pressure is there. Altogether, little proportion of forests in relation to other districts can be directly attributed to harsh physiographic conditions and partly to human activities. Uttarkashi accounts for about 39 per cent, Chamoli for 33.6 per cent and Pithoragarh for 29.3 per cent forest cover, which are well below the state average (45.7%).

Altogether, little proportion of forests in relation to other districts can be directly attributed to harsh physiographic conditions and partly to human activities. Uttarkashi accounts for about 39 per cent, Chamoli for 33.6 per cent and Pithoragarh for 29.3 per cent forest cover, which are well below the state average (45.7%).

All other districts such as Tehri Garhwal, Pauri Garhwal, Almora, Nainital, Champawat and Bageshwar have their forest cover above the state average. Only Nainital and Champawat are close to ecological threshold of mountain areas of 66 per cent forest cover (Table 2.2). It can be generalized that Shivalik region of the state has less forests due to anthropogenic pressure. Middle Himalayan region has a large area under forest cover due to limited anthropogenic pressure and favourable environmental conditions for forest growth, whereas high Himalayan regions, though have limited anthropogenic pressure, have less forests due to very low temperature being the limiting factor for forest growth (Figure 2.2).

Middle Himalayan region has a large area under forest cover due to limited anthropogenic pressure and favourable environmental conditions for forest growth, whereas high Himalayan regions, though have limited anthropogenic pressure, have less forests due to very low temperature being the limiting factor for forest growth (Figure 2.2).

Change of forest cover at district level in Uttarakhand during 2001-2005 is depicted in Figure 2.3. It is depicted from the figure that forest cover has declined in Nainital (20 sq km), Rudraprayag (33 sq km) and Udhamsingh Nagar (205 sq km). The districts of Chamoli, Dehradun, Pauri Garhwal show substantial improvement in forest cover as 115 sq km, 107 sq km and 129 sq km respectively. While the districts of Almora, Bageshwar, Tehri Garhwal and Uttarkashi show a marginal improvement in forest cover as 82 sq km, 83 sq km, 74 sq km and 73 sq km respectively. Singh and Mishra (2005) also studied the forests of Uttarakhand region for about previous three decades and reveals that forest cover has declined in almost all the districts except Dehradun and Tehri Garhwal.

The districts of Chamoli, Dehradun, Pauri Garhwal show substantial improvement in forest cover as 115 sq km, 107 sq km and 129 sq km respectively. While the districts of Almora, Bageshwar, Tehri Garhwal and Uttarkashi show a marginal improvement in forest cover as 82 sq km, 83 sq km, 74 sq km and 73 sq km respectively. Singh and Mishra (2005) also studied the forests of Uttarakhand region for about previous three decades and reveals that forest cover has declined in almost all the districts except Dehradun and Tehri Garhwal.

Wildlife of Uttarakhand:

Uttarakhand is a rich state in terms of wildlife. It is habitat of a few species, which are considered globally threatened, such as tiger, leopard, elephant, black bear, brown bear, etc. Wildlife of Uttarakhand has undergone significant changes in recent past (Jhala et al., 2008) musk deer, leopard, tiger, bear elephant, which were once found in abundance, are now found in some forest pockets only.

However, conservation efforts have been helpful upto some extent in improving and conserving these animals in recent past. Elephants are restricted to the Rajaji National Park and Jim Corbett National Park only (Jhonsingh and Negi, 2003).

While, tiger and leopard are found in Rajaji and Jim Corbett and in some forest pockets of Chamoli, Rudraprayag, Tehri and Pauri Garhwal. Black bear has reduced significantly in Shivalik region of Uttarakhand. It has improved in the district of Chamoli. Presently, the total number of tigers, leopard, elephant, chital, black bear and musk deer has been estimated as 245, 2,090, 1582, 35,000, 375 and 160 respectively (Table 2.3). Climate Change in Uttarakhand:

Climate Change in Uttarakhand:

Climate change refers to the long-term fluctuations in temperature, precipitation, wind and other elements of earth’s climate (CPCB, 2002). It has always been the nature’s part of evolution, which has been changing constantly in every geological era.

It is a natural phenomenon, rate of which has been accelerated by anthropogenic activities such as land use/cover change, greenhouse gas emission, deforestation, overexploitation of natural resources after industrial revolution (1870) in general and in later half of 20th century in particular.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that the global average surface temperature has increased by 0.6° ± 0.3° C over the 20th century and is projected to further increase from 1.4° to 5.8° C by the end of 21st century relative to 1990. Altogether temperature is expected to increase about 2° C till 2030 and about 4° C till 2090 relative to pre-industrial levels (IPCC, 2001).

Climate change has become a matter of grave concern after Rio Declaration-1992 due to its potential impacts on earth’s ecosystem. Natural systems are vulnerable to climate change because of their limited adaptive capacity.

The natural systems which are vulnerable include glaciers, tropical forests, mangrove, alpine ecosystem, etc. Some of the systems may undergo significant and irreversible damage. In fact, the natural system operates in such a way that any change in any part of the environment at any place in a specific time period is counterbalanced by inbuilt self-regulating mechanism of environment, thus the equilibrium is restored.

However, man has modified and altered the natural system to such an extent that the equilibrium cannot be restored by inbuilt self-regulatory system (Singh, 2004). Consequently, the modified environmental conditions adversely affect the functioning of sub-systems. Presently, the adverse effects of modified environmental system are so rapid that biological communities and other physical processes are not able to keep pace with these modifications.

Climate of Uttarakhand has changed over the years. Studies done on various elements of climate, i.e., rainfall and temperature using instrumental records and proxy records of palaeo-botany and palaeo-ecology, etc., by various researchers in various parts of Uttarakhand confirm the climate change.

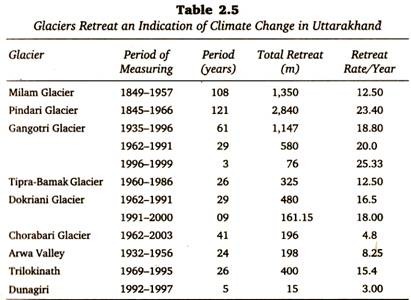

Glaciological studies are also a good source to study the climate of any region, since glaciers quickly and sharply respond to changing climate. Rising temperature results in shrinkages of glaciers, while on the other end, falling temperature indicates glacial advancement (Kumar, 2005; Mishra, 2007).

Thus, long-term study of glaciers in absence of instrumental records of temperature is a handy source of information for climate change. Such studies become even more vital in higher Himalayan region, where long-term and even short-term climatic data are not available. Instruments have yet not been installed in many high altitude districts of Uttarakhand.

Therefore, studies on glaciers are handy for climate change in such region. Analysis of tree rings (Palaeo-botany and Palaeo-ecology) also provides useful information about the climate change. Few Palaeo-botanical and Palaeo-ecological studies even have questioned some of the well-established facts of climate change, such as Little Ice Age (LIA) and its impacts in western Himalayan regions. In this book, climate change is to be analyzed on the basis of physiography of the state. Firstly, the climate change will be analyzed in Shivalik region of Uttarakhand, subsequently in middle and high Himalayan region.

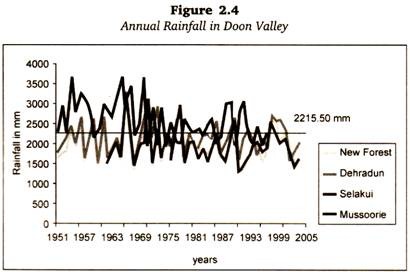

Thakur (2007) studied the climate change of Doon valley, which is the part of Shivalik region of Uttarakhand state. He mentioned declining trend of annual rainfall in later half of last century (Figure 2.4). Range of rainfall has declined during 1970s and 80s, which increased marginally in subsequent years. While frequency of rainy days shows a reverse trend. In all four meteorological stations, i.e., Dehradun, Mussoorie, Selakui and New Forests area, frequency of rainy days increased marginally during 1970-80-90s, while it declined marginally in subsequent years (Table 2.4). As far as rainfall variability is concerned, it has increased over the later half of last century in all the four observation centres.

In all four meteorological stations, i.e., Dehradun, Mussoorie, Selakui and New Forests area, frequency of rainy days increased marginally during 1970-80-90s, while it declined marginally in subsequent years (Table 2.4). As far as rainfall variability is concerned, it has increased over the later half of last century in all the four observation centres.  Rainfall variability, which was nearly 39 per cent during 1950-60 at New Forests area and Dehradun in Doon valley, increased up to nearly 42-43 per cent during the last decade of the last century, i.e., 1990-2000. With regard to temperature in Doon valley, researcher concludes that valley is experiencing an increase in average maximum temperature and decrease in average minimum temperature. The diurnal temperature range has increased.

Rainfall variability, which was nearly 39 per cent during 1950-60 at New Forests area and Dehradun in Doon valley, increased up to nearly 42-43 per cent during the last decade of the last century, i.e., 1990-2000. With regard to temperature in Doon valley, researcher concludes that valley is experiencing an increase in average maximum temperature and decrease in average minimum temperature. The diurnal temperature range has increased.

Palaeo-botanical and Palaeo-ecological studies (tree rings analysis) near Gangotri group of glaciers also confirm the climate change in the region. In such studies, growth of trees is analyzed using tree rings. Eventually, it is correlated with rise or fall of temperature. High growth of trees is said to be associated with rising temperature and vice-versa.

Bhattacharya et al. (2006) and Singh and Yadav (2000) did such studies near Gangotri glacier system to study the climate change and responses of glaciers. They constructed the climatic history of about 425 years (Figure 2.5). Studies reveal that tree growth has increased after 1950 and it was highest in the decades of 1990s. Similarly, climatic records of northern hemisphere show that 1990 was the warmest decade in last millennium with 1998 being the warmest year. Glaciological studies also reveal that retreat rate of Gangotri glaciers has increased. Thus, it can be safely generalized that average temperature has increased in the Uttarakhand region over the last century.

Similarly, climatic records of northern hemisphere show that 1990 was the warmest decade in last millennium with 1998 being the warmest year. Glaciological studies also reveal that retreat rate of Gangotri glaciers has increased. Thus, it can be safely generalized that average temperature has increased in the Uttarakhand region over the last century.

Also average temperature of winters has increased in the region. Bhattacharya et al. (2006) also questioned the presence of LIA and its impact in this part of Himalaya. Study eventually indicates that impact of LIA was not severe in this part of Himalaya. Climatic study done by Lui and Chen (2000) in Tibetan plateau also supports above facts.

It has been reported that last few decades have been characterized by constant rise in global average temperature (Roy and Singh, 2002). Studies show that if climate change continues with present pace, ecosystem in some cases will run out of space (CPCB, 2002) and in near future additional environmental stress will be mounted on the already fragile ecosystem (Halpin, 1994).

Mountains are particularly vulnerable and sensitive to climate change. Impact of climate change is clearly visible in mountain regions in the form of glaciers shrinkages (Mishra, 2007), changes in species composition, invasion of non-native species and altitudinal movement of ecosystem (IPCC, 2002; Halpin, 1994; CPCB, 2002). As stated above that glacial fluctuations are closely associated with fluctuation in climate, thus shifting of glacier’s snout is the best indicator of study climate change over a period of time (Dobhal et al., 2004). Historical account of glaciers retreat in Uttarakhand region has been given in Table 2.5. It can be depicted from the table that Pindari, Gangotri and Dokriani glaciers are retreating rapidly and others are retreating slowly. This clearly indicates changing climate in Uttarakhand.

As stated above that glacial fluctuations are closely associated with fluctuation in climate, thus shifting of glacier’s snout is the best indicator of study climate change over a period of time (Dobhal et al., 2004). Historical account of glaciers retreat in Uttarakhand region has been given in Table 2.5. It can be depicted from the table that Pindari, Gangotri and Dokriani glaciers are retreating rapidly and others are retreating slowly. This clearly indicates changing climate in Uttarakhand.