In this article we will discuss about the meaning and composition of nucleoid.

Meaning of Nucleoid:

The genetic material of prokaryotic (bacterial) and eukaryotic cells differ variously and, probably, the most striking difference between them is the manner in which the genetic material is packaged. Eukaryotic cells possess two or more chromosomes contained within the ‘nucleus’ whereas the prokaryotic cells lack the nucleus and have a large, free-lying, double-stranded DNA molecule in their cytoplasm.

This DNA molecule is called bacterial chromosome, which aggregates to form a visible mass called the nucleoid (nuclear body, chromatin body, nuclear region are the other names used) (Fig. 5.33).

Although the occurrence of single, naked, and circular bacterial chromosome has been considered to be the most common features since long but, as the recent studies reveal, it is not a rule because exceptions to these prevail in bacterial cells.

Recently, it has been discovered that some bacteria such as Vibrio cholerae and Rhodobacter sphaeroides have more than one chromosome, and membrane-bound DNA containing regions have been found in two bacterial genera, namely, Pirellula and Gemmata. Pirellula has a single membrane that surrounds a region called pirellulosome, which contains a fibrillar nucleoid and ribosome-like particles.

The nuclear body of Gemmata obscuriglobus is delimited by two membranes. The chromosome of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, is linear. Although uncommon, linear chromosomes are now known to be present in some other bacteria including Streptomyces, an important antibiotic-producing filamentous bacterium (actinomycete).

The nucleoid becomes visible in the light microscope after staining with the feulgen stain, a stain that specifically reacts with DNA. Electron microscopic photographs of actively growing bacteria show that the nucleoid has projections that extend into the cytoplasmic matrix (Fig. 5.34).

It is presumed that these projections contain DNA that is being actively transcribed to produce mRNA. Electron microscopic studies of nucleoids often show that they remain in contact with either mesosomes or the plasma membrane.

Pieces of membrane also are found attached to isolated nucleoids. These evidences suggest that the bacterial chromosome remains attached to membrane of the cell, and the membrane may play significant role in the separation of DNA into daughter cells during cell-division.

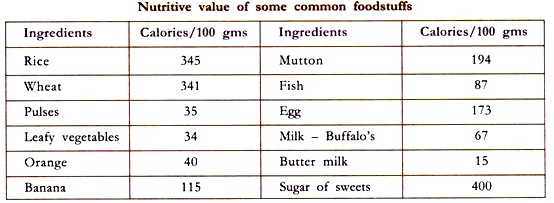

In Table 5.3 the number, size and configuration of those prokaryotic (bacterial and archaebacterial) chromosomes are given which have been completely sequenced.

Composition of Nucleoid:

Nucleoids have been isolated intact and free from membranes. When chemically analysed, they are found composed of about 60% DNA, 30% RNA, and 10% protein (mostly RNA polymerase) by weight.

The DNA is looped and coiled extensively with the aid of RNA and nucleoid proteins which are different from the histone proteins occurring in eukaryotic nuclei and are recognised by different names such as HU, NS and DNA- binding protein-II.

However, following two features of bacterial DNA are particularly distinctive:

(i) Lack of histone proteins:

Contrary to the eukaryotic organisms in which the DNA is packaged by wrapping of around special beads of protein called histones to form structure called ‘nucleosome’, the monerans (prokaryotes) have no histone proteins and no nucleosome.

(ii) Lack of introns:

Eukaryotic DNA, which codes for protein is interrupted by noncoding sequences (introns). The latter are absent in bacteria.