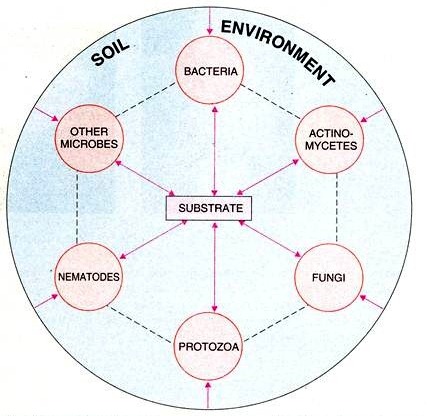

Microorganisms which live in soil are algae, bacteria, actinomycetes, bacteriophages, protozoa, nematodes and fungi (Fig. 30.2).

A brief description of soil microorganisms has been given below:

1. Soil Algae:

Soil algae (both prokaryotes and eukaryotes) luxuriantly grow where adequate amount of moisture and light are present. They play a variety of roles in soil. One of the important role of blue-green algae is that it has revolutionised the field of agriculture microbiology due to use of cyanobacterial biofertilizer.

On the other hand they can also be used in reclamation of sodic soil i.e. alkaline soil, sewage treatment, etc. The prominent genera are Anabaena, Calothrix, Oscillatoria, Aulosira, Nostoc, Scytonema, Tolypothrix, etc.

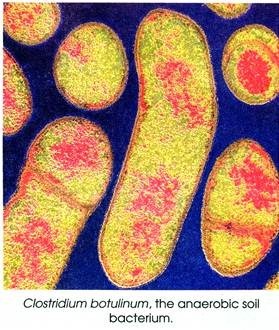

2. Bacteria:

Bacteria are the smallest unicellular prokaryotes (0.5 – 1 × 1.0 – 2.0 µm), the most abundant group and usually more numerous than others, the number of which varies between 108 and 1010 cells per gram soil. However, in an agriculture field their number goes to about 3×109/g soil which accounts for about 3 tonnes wet weight per acre.

Based on regular presence, bacteria are divided into two groups:

(a) Soil indigenous (i.e. true resident) or autochthonous, and

(b) Soil invader or allochthonous.

Moreover, the number and types of bacteria are influenced by soil types and their microenvironment, organic matter, cultivation practices, etc. They are found in high number in cultivated than virgin land, maximum in rhizosphere and less in non-rhizosphere soil possibly due to aeration and nutrient availability.

The inner region of soil aggregates contained higher level of Gram-negative bacteria, while the outer region contained higher level of Gram-positive bacteria. This may be due to polymer formation, motility, surface changes, and life cycle of bacteria involved.

Bacteria do not occur freely in the soil solution but are closely attached to soil particles or embedded in organic matter; even after adding the dispersing agents bacteria are not completely dislodged from the soil particles and distributed in suspension as individual cell.

Moreover, they play a major role in organic matter decomposition, bio-trans- formation, biogas production, nitrogen fixation, etc. Example of some of soil bacteria is Agrobacterium, Arthrobacter, Bacillus, Alcaligens, Clostridium, Corynebacterium, Erwinia, Nitrosomonas, Nitrobacter, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Thiobacillus, etc.

3. Actinomycetes:

Actinomycetes share the characters of both bacteria and fungi, and they are commonly known as “ray-fungi” because of their close affinity with fungi. They are Gram-positive and release antibiotic substances. However, the earthy odour of newly wetted soils has been found to be a volatile growth product of actinomycetes.

Population of actinomycetes in soil remains greater in grass land and pasteur soil than in the cultivated land. In temperate zones the number of actinomycetes ranges from 105 to 108 per gram soil.

The most limiting factor is the pH which governs their abundance in soil. Its luxurient growth is favoured by neutral or alkaline pH (6.0 to 8.0). The important members of actinomycetes are: Actinomyces, Actinoplanes, Micromonospora, Microbispora, Nocardia, Streptomyces, Thermoactinomyces, etc.

4. Bacteriophages:

Bacteriophages as well as plant and animal viruses have been observed in the soil. However, there role has not been clearly understood.

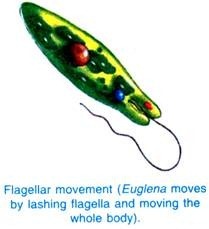

5. Protozoa:

In moist soil most of the members of microfauna remain in encysted form. The population of each group is 103 per gram wet soil. The role of soil protozoa is predatory, as these eat upon bacteria and thereby regulate their population.

However, the number of protozoa can be correlated with plant root growth and indirectly with status of soil nutrients. Interaction of soil-amoebae with fungal hyphae has been discussed in section Microbial Interactions.

Fig. 30.2 : Microbial world of soil environment showing possible interactions between microbes and energy substrate, microbes and physical factors and between the microbes themselves (energy substrates include inorganic chemicals, dead organics and living plant root and soil fauna)

Fig. 30.2 : Microbial world of soil environment showing possible interactions between microbes and energy substrate, microbes and physical factors and between the microbes themselves (energy substrates include inorganic chemicals, dead organics and living plant root and soil fauna)

6. Nematodes:

Until the role of nematodes in soil was understood nematology was in infancy stage. In recent years the ecology of nematodes has been greatly advanced. Nematodes derive nutrients for their growth and reproduction from the cell contents and cytoplasm of protozoa, bacteria, fungi, etc. Some common example of protozoa is Colpoda, Pleurotricha, Heteromita, Cercomonas, Oikomonas, Phalansterium, etc.

7. Fungi:

In most of aerated or cultivated soils fungi share a major part of the total microbial biomass because of their large diameter and extensive net work of mycelium. However, population of soil fungi ranges from 2 × 104 to 1 × 106 propagules per gram dry soil and its number differs according to isolation procedure and composition of media.

Fungi derive nutrients for their growth from organic matters, living animals (including protozoa, arthropods, nematodes, etc.) and/or living plants establishing different types of relationships. Garrett (1950) classified the soil fungi on the basis of substrate-specialization (i. e. fundamental niche) and duration of parasitism as given in Fig 30.3.

The root inhabiting fungi are characterized by an expanding parasitic phase on the living host with a little declining saprophytic phase after the death of the invaded host. But the soil inhabiting fungi are characterized by the ability to survive indefinitely as soil saprophyte.

Success in competitive colonization of substrate by any particular soil fungus depends directly on its competitive saprophytic ability (CSA), inoculum potential at the surface of the substrate, and inversely as the aggregate inoculum potential of the competing fungi.

Many unspecialized root infecting fungi can probably exist as competitive soil saprophytes in the absence of living host, they have characteristics that confer a high degree of competitive saprophytic ability such as:

(a) a high mycelial growth rate allied to rapid germination of resting propagules when stimulated by nutrient diffusion from a potential substrate,

(b) a sufficient arrangement of tissue-degrading enzymes,

(c) production of fungistatic growth products including antibiotics,

(d) tolerance of those produced by other microorganisms.

However, most specialized parasites have evolved in such a way as to cause minimum possible damages to the host plant functioning as a piece of biological machinery existing for support and protection of parasite.

The distribution of specialized parasite is determined by its host species. Some of the soil saprophytes are: Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Dematium, Gliocladium, Helminthosporium, Humicola, Metarrhizium, etc., and fungi associated with plant disease are: Armillaria, Fusarium, Helminthosporium, Ophiobolus, Phytophthora, Plasmodiophora, Pythium, Rhizoctonia, Sclerotium, Thielaviopsis, Verticillium, etc.