The below mentioned article provides an overview on Evolution of Classification of Flowering Plants in India. After reading this article you will learn about: 1. Introduction to Evolution of Classification 2. Types of Systems of Classification.

Introduction to Evolution of Classification:

In India, botanical science had its origin in a very remote age with the development of agriculture, when Indians of the Vedic Period (2000 B.C. – 800 B.C.) cultivated various food crops. In the Vedic literature several technical terms are used in the description of plants and plant parts. Both the external features and the anatomy were studied.

One of the most ancient works dealing with plant life in scientific manner is the Vrikshayurveda (science of plants and plant life), compiled by Parasara even before the beginning of the Christian era, and which formed the basis of botanical teaching and the medical studies in ancient India.

This ancient work deals with the morphology and anatomy of the plant organs, nature and properties of soil, description and distribution of forests in the country, etc.

According to Parasara there are innumerable cells (rasakosa) which serve as storehouse of sap derived from the soil, through the roots by transporting system (syandani) and that the sap is digested with the help of chlorophyll (ranjakena pacyamanat) into nutritive substances and by-products.

A system of classification was formulated, and the plants were divided into eight groups:

1. Vriksha;

2. Vanaspati;

3. Guccha;

4. Gulma;

5. Trina;

6. Aushadhi;

7. Valli and

8. Kashtha Charaka was devoted for medicinal plants, and he wrote the famous work Charaka Samhita.

The ancient system of classification was formulated based on the study of the comparative morphology of plants, which according to Majumdar was more advanced than any system developed in Europe before the eighteenth century. Many families (ganas) were clearly distinguished as to be recognizable today.

The present day family Cruciferae was called Swastikaganiyam because the calyx resembles a Swastika, and was characterized by having superior ovary, four free sepals, four free petals, six stamens two of which are shorter and two carpels fused and forming a two-locular fruit.

The present day Cucurbitaceae was known as Tripusaganiyam and was characterized by having flowers which were epigynous, sometimes bisexual with five sepals, five fused petals, three stamens and a trilocular ovary with three rows of ovules.

In middle ages there was an extraordinary rise of Islam among the Arabians who spread their culture from Spain to Bokhara. Islamic scholars contributed a lot to the botanical science. A Persian writer Abu Mansur wrote a book on medicinal plants, also referred Indian plants.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna) (980 – 1037A.D.) also a Persian, compiled a book Canon of Medicine containing numerous medicinal plants, which was much valued and had more than twenty editions in the sixteenth century.

The problem of classifying the heterogenous groups of angiosperms is very interesting and as well as too tough for taxonomists. The angiosperms are widely distributed with so many variations that sometimes it seems almost impossible to arrange them in systematic order.

Since the prehistoric times the people were interested in the solution of the problem, and for the first time a few plants were classified according to their medicinal and food value and thus the taxonomy of flowering plants originated. After the discovery of some useful plants, the mind of the people of the past diverted towards the cultivation of food producing and other beneficial plants.

They prepared fields, sown the seeds and harvested the crops which were assumed to be God given gifts.

There can be three different possible types of systems of classification, the artificial, the natural and the phylogenetic classifications:

1. Artificial System:

In artificial system of classification only a few characters of the plants are being considered, for example, the grouping of plants into herbs, shrubs and trees or the sexual system of Linnaeus based on number of stamens and styles.

There are so many drawbacks in this system the most important one is that the plants closely resembling each other are very often placed in widely separated groups, while those quite different from each other are being placed in the same group.

This system can be compared to the alphabetical arrangement of words in a dictionary, where two words arranged one after the other have nothing to do with each other. The artificial systems are not commonly in current use. The best known artificial system is of Linnaeus published in 1735.

2. Natural System:

In the natural system all the important characters of the plant are being considered, and the plants are classified according to their related affinities. This system reflects the situation as it is thought to exist under natural conditions, e.g., Bentham and Hooker’s system (1862-83).

3. Phylogenetic System:

In phylogenetic system, the plants are classified according to their evolutionary and genetic affinities. But it seems a bit difficult to classify the plants perfectly on the basis of evolutionary tendencies due to imperfection of fossil records, and therefore, at present the plants are classified partly according to natural and partly according to phylogenetic basis.

The systems of classification proposed by Engler in 1886, by Hutchinson in 1926, and by Tippo in 1942 are phylogenetic. The plant taxonomy begins with the Greeks.

Types of Systems of Classification:

Ancient Systems of Classification:

From Theophrastus to Linnaeus:

Theophrastus (370-285 B.C.), the father of Botany, was a pupil of Plato (426-347 B.C.) and friend of Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) classified plants on the basis of form and texture. In his Historia Plant-arum he had classified and described about 450 cultivated plants. He had classified them as herbs, under-shrubs, shrubs and trees.

Theophrastus considered the trees to be highest evolved while herbs very primitive. He also distinguished between annual, biennial and perennial plants. He also noted the difference between centripetal and centrifugal inflorescences. His classification was strictly artificial.

Dioscorides (64 A.D.) of Christian era prepared a ‘Materia Medica’ and described many plants of medicinal value, but his descriptions were imperfect and classification of little importance.

Pliny (23-79 A.D) also a botanist of Christian era had written seventeen volumes on the subject and gave many details of the cultivation of gum and spices yielding plants. He had described medicinal plants in three volumes of his great work, ‘Historia Naturalis’ (77 A.D.), largely compiled from Greek authors.

Albertus Magnus (1193-1280), for the first time distinguished between monocotyledons and dicotyledons on the anatomical basis with the help of crude lenses available at that time. In his De vegetalis he had described many plants and methods of gardening and orcharding.

Otto Brunfels (1464-1534), could recognise for the first time between perfecti and imperfecti groups of plant kingdom on the basis of the presence and absence of flowers. Sometimes it is also said that modern study of systematic botany has started from the time of Brunfels.

Jerome Bock (1498-1554), classified the plants as trees, shrubs, and herbs but he tried to follow the natural system of classification and brought many plants close to each other according to their related affinities.

William Turner (1512), is the acknowledged ‘Father of English Botany’ and was the author of several botanical works. He wrote the first English Herbal. In this work the arrangement is alphabetical and the woodcuts are inferior to those of Brunfels. The work was published in three parts.

The Herbal of Valerius Cordus (1561) of Wittenberg showed a great advance and is a landmark in descriptive botany.

Andrea Caesalpino (1519-1603), an Italian botanist and physician, wrote a set of sixteen volumes on plants. The first volume was philosophical describing some minor differences of cultivated and wild plants, trees and shrubs, shrubs and herbs and some medicinal plants. In the other fifteen volumes he divided the plant kingdom into fifteen heterogeneous groups.

In his work De plants published in 1583, he classified about 1500 plants chiefly on the basis of the characters of the seed and embryo. He classified the plants first on the basis of their habit (trees and herbs) and then subdivided them on the basis of their characters of the seed and embryo.

He classified the plants first on the basis of their habit (trees and herbs) and then subdivided them on the basis of their characters of the seeds and fruits. He also used the characters like the presence or absence of bulbs, presence of latex and number of locules, etc.

He prepared a herbarium of 768 plants which still exists as one of the oldest herbaria. Caesalpiono’s work was remarkable in that time to classify the whole plant kingdom but it also lacked in many ways.

The most important of the British herbals was written by John Gerard (1545-1612) entitled Herbal or General Historie of Plante. This was published in London in 1597. The groups of plants recognised are based on well marked characters of general form, manner of growth and economic uses.

They started with supposed simpler forms, grass-like plants with narrow leaves, and advanced through the broader-leaved bulbous and rhizomatous monocotyledons to dicotyledonous herbs, culminating in shrubs and trees, the latter being regarded as the most perfect.

Jean Bauhin (1541-1613), a Swiss physician, wrote an illustrated Historla Plantarum Universalis which was published after his death in 1650-51 in three volumes, which contained the descriptions of about 5,000 plants with 3,500 illustrations.

G. Bauhin (1560-1624), a Swiss botanist and brother of Jean Bauhin wrote “An Introduction to Botany” in which he described about 6,000 species of plants. He also made considerable advance in the frequent use of binomial nomenclature.

He described many plants with generic and specific names. His great work ‘Phytopinax’ of 1596 is great contribution of Botany. Many of the plant descriptions of Bauhin’s work are very much alike modem description of species.

M. de Lobelius (1538-1616), he differentiated between monocotyledons and dicotyledons chiefly on the basis of leaves. He clearly recognized certain natural affinities in plants. His great work ‘Kruydtboeck’ was published in 1581, which contains many excellent illustrations.

Robert Morison (1620-1683), published his Plantarum Historia Universalis at Oxford in 1680. His system much resembles that of Caesalpino. Woody plants are kept distinct from herbaceous, and the latter are divided into fifteen sections based partly on habit and partly on characters derived from the fruit and seed.

Morison had the distinction of publishing the first systematic monograph of a limited group. This was his Plantarum Umbelliferarum Distribution Nova, issued in Oxford in 1672. The arrangement is based on the form of the fruit, which is still employed for the classification of Umbelliferae.

John Ray (1628-1705), an English botanist contributed much and the foundation of modern Botany was laid. His most important work was the ‘Historia Plantarum’ which was published in three volumes between 1686 and 1704. He clearly showed the importance of the monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous nature of the embryo from the point of view of related affinities and classification.

He divided the plant kingdom in two main groups:

A. Herbae, and

B. Arbores.

For the first time he used the terms Dicotyledons and Monocotyledons. In descriptions he used many binomial names.

His classification was as follows:

Herbae:

(i) Imperfecti (flowerless)

(ii) Perfecti (flowering)

(a) Dicotyledons (with two cotyledons),

(b) Monocotyledons (with one cotyledon).

Arbores:

(i) Dicotyledons (with two cotyledons).

(ii) Monocotyledons (with one cotyledon).

J.P. de Tournefort (1656-1708), is said to be the founder of the concept of modem genera. Though generic names were used before, yet Tournefort was the first to provide genera with descriptions and placed them definitely apart from species. His classification was inferior in many ways to John Ray’s classification. He never distinguished between Cryptogams and Phanerogams whereas monocots and dicots.

He classified the plants on the basis of presence and absence of petals. He called the plants with petals as Petalodes and without petals as Apetali. His famous work Elements de Botanique was published in 1684 which was later translated into Latin.

Camerarius (1665-1721), a German botanist could demonstrate for the first time the sexuality in the flowering plants on the experimental basis. He proved experimentally that pollen is absolutely necessary for fertilization and seed formation in the life history of plants.

Modern Systems of Classification:

From Linnaeus to Hutchinson:

Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778), a great Swedish botanist and said to be the father of modem botany was born in 1707. Only due to this great man, botany and other sciences got inspiration and expanded day by day. From the time of Linnaeus actually the concept of modern botany began. He followed the binomial system of nomenclature and described hundreds of plants from different parts of the world.

He also revised many older genera and gave great stability to species. He published a number of important works, e.g.. Genera Plantarum, Species Plantarum, Flora Lapponica, etc., in which he described hundreds of plants known in that time. Linnaeus proposed an artificial sexual system of classification containing twenty-four classes.

The plants were classified on the basis of number, cohesion, length and certain other characters of stamens. The outline of the classes of his system was published in his Systema Naturae in 1735, and again in General Plantarum in 1737 along with all the known plants of that time arranged systematically.

The outline of the classification followed by him is as follows:

Though system was artificial, yet due to its simplicity and easy way of identification of plants, the system continued for more than one hundred years after the death of Linnaeus. He recognised the weakness of his system and was fully aware of the shortcomings.

He attempted once again a more natural system but anyhow he could not complete it. On the whole, whatever Linnaeus presented to the scientific world is undoubtedly remarkable and of great value.

B.de Jussieu (1699-1777) and A.L.de Jussieu (1748-1836). The two French botanists Bernard de Jussieu and his nephew A.L. de Jussieu at the end of eighteenth century proposed a scheme of classification which was based upon the sexual system of Linnaeus but in an improved form B. de Jussieu made many changes in the classification of Linnaeus and more or less gave a new form to it, but this was never published. His nephew, A.L. de Jussieu modified his uncle’s plan with many changes and published it in his own way, in his famous work ”Genera Plantarum” in 1789.

He included fifteen classes and more than one hundred orders (now known as families) in his system. His system was chiefly based on the number and position of cotyledons and adhesion of petals. His system of classification can be claimed to be a natural one.

The outline of his plan is as follows:

Michel Adanson (1727-1806), published his Families des plantes in Paris in 1763. This contains an exhaustive account of previous systems, and an arrangement of genera in fifty-eight families, which are named and characterized.

A.P. de Candolle (1778-1841), a great French botanist proposed a very reasonable natural system of classification. In his younger days, he spent much of his time at Paris but after 1816 he shifted to Geneva, Switzerland, where he carried out several researches and made the city centre of botanical research. He wrote many monographs concerning classification and plant families, he was also interested in Physiology and Plant Geography.

His famous work “Theorie elementaire de la botanique” was published in 1813, in which he proposed a classification completely based on natural system. He declared certain principles which later provided the base of origin of Bentham and Hooker’s classification.

His system contains 161 orders or families. The last edition of his “Theorie elementaire” was published in 1844 by his son Alphonse de Candolle in which he gave 213 orders or families.

The outline of de Candollean classification is as follows:

Vasculares:

Plants with vascular bundles or plants with cotyledons.

Class 1. Exogenae:

Dicotyledoneae, embryo with two cotyledons and vascular bundles arranged in a ring.

A. Diplochlamydeae:

Flowers with two whorls of perianth, i.e., calyx and corolla both present.

(a) Thalamiflorae:

Flowers polypetalous and hypogynous.

Cohort 1:

Carpels many and stamens opposite the petals, orders 1-8 Ranunculaceae, Berberidaceae, etc.

Cohort 2:

Carpels solitary or joined; placenta parietal, order 9-20. Cruciferae, Violaceae, etc.

Cohort 3:

Ovary solitary; placenta central, orders 21-44. Caryophyllaceae, Malvaceae, etc.

Cohort 4:

Fruit gynobasic, orders 45-46.

(b) Calyciflorae:

Flowers perigynous or epigynous, stamens inserted on the calyx tube, orders 47-84.

(c) Corolliflorae:

Flowers gamopetalous and hypogynous, stamens epipetalous, orders 85-108.

B. Monochiamydeae:

Flowers with single whorl of perianth, orders 109-128.

Class 2: Endogenae:

Monocotyledoneae, embryo with single cotyledon; vascular bundles scattered.

A. Phanerogamae:

Flowers present, i.e., visible and regular, orders 129-150.

B. Cryptogamae:

Flowers absent, orders 151-155.

Cellulares:

Plants without vascular bundles and cots.

Class 1:

Foliaceae – Leafy; sexuality known, orders 156-157 (mosses and liverworts).

Class 2:

Aphyllae – Not leafy; sexuality unknown, orders 158-161 (algae, fungi, lichens).

A.P. de Candolle’s system was definitely superior to Jussieu’s system of classification including about 161 orders (families) of plants as compared with 167 families of Jussieu and Linnaeus respectively. The last edition of de Candolle’s “Theorie elementaire” was published by his son Alphonse de Candolle in 1844, which contained 213 orders or families.

Robert Brown (1773-1858), The name of Robert Brown seems fairly large in the chronicles of systematic botany, because he has often been referred to as botanicorum facile princeps. Brown was the first keeper of the Botanical Department of the British Museum.

In 1810 Brown published his Prodromus Florae Noval Hollandiae, containing descriptions of Australian plants collected by Banks and Solander. In 1827 Brown published a paper entitled, ‘The female flower in Cycadaceae’ and Coniferae, and in this he announced the important discovery of the distinction between Angiosperms and Gymnosperms.

John Lindley (1799-1865), an English botanist, who was Professor of Botany at the University College, proposed a system of classification and published “Introduction to the Natural order of Plants”. His system was based on de-Candollean system with few remarkable improvements.

Stephen Endlicher (1804-1849), was a prominent systematist of the first half of the nineteenth century. His scheme of classification was published in “Genera Plantarum Secundum Ordines Disposita” in 1836-40 which was widely used in the continental countries.

He divided the plant kingdom into two main groups:

1. Thallophyta,

2. Cormophyta.

In Thallophyta he included algae, fungi and lichens while in Cormophyta mosses, ferns and seed plants were included. In his published work “Genera plantarum” he described 6,235 vascular plants.

Henri Baillon (1827-1895), Henri Baillons’ Histoire des plantes (1867-1895), a work of thirteen volumes, contains useful descriptions of the families and genera of flowering plants. Its chief merits, however, are the splendid illustrations with accurate dissections. He also published monographs on Euphorbiaceae and Buxaceae, etc. accompanied by beautifully reproduced plates.

In 1851, Hofmeister carried out many brilliant researches and established the existence of alternation of generations in lower as well as in higher plants. Following the researches of Hofmeister in 1859, Charles Darwin published his famous doctrine of evolution “Origin of Species”.

The doctrine of evolution was known to every educated man in the world, which brought revolutionary changes in solving the problem of classification of plants and animals.

Bentham and Hooker, the well known English systematists, established an important system of classification which appeared in the last half of the nineteenth century. George Bentham (1800-1884) and Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911), two English botanists, whose researches were carried over at the great herbarium of the Royal botanical garden at Kew.

After the death of his father Sir W.J. Hooker, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker was director of the Kew gardens for twenty years.

Bentham and Hooker published a joint system of classification, containing 202 orders (families) in a monumental work “Genera Plantarum” (1862-1883) which became most popular classification in European countries except France for many years.

The system of classification by Bentham and Hooker is based on that of De Candolle’s and Jussieu’s systems, but it is a great improvement over those and other previous schemes.

An outline of Bentham and Hooker’s classification is given below:

Merits and Demerits of Bentham and Hooker’s System of Classification:

Merits:

Though this system is not very natural, yet it is very easily workable, and is important from the point of view of its field applications. The system has been worked out as a result of very careful comparative examination of all the known genera of phanerogams.

There are 202 orders (now known as families) beginning with Ranunculaceae and ending in Gramineae. This system was accepted by entire British Empire, U.S.A. and other European countries. Even today many botanists follow this classification because of its simplicity. This classification makes the basis for the arrangement of plants in Kew Herbarium and other important herbaria of Commonwealth Countries.

A special feature of this system is the addition of the Disciflorae and a curious arrangement of dividing certain groups on the basis of aquatic or terrestrial characteristics.

In this system, the greater emphasis has been given on the contrast between free and fused petals, e.g., the Dicots are divided into the three groups Polypetalae, Gamopetalae and Monochlamydeae.

In Monocots, the stress is being given to the relative position of ovary and perianth characteristics.

Demerits:

The greatest disadvantage of this system is the retention in the group Monochlamydeae, a number of orders which show affinities with those in which a biseriate perianth is the rule.

The position of Gymnosperms between Dicots and Monocots is only for convenience rather than an indication of affinities.

This system of classification is based mainly on single and mostly artificial characters, with the result the closely related families are widely separated from each other.

The extreme simple nature of the parts of certain orders such as Salicineae, Cupuliferae, etc. indicates an affinity with an early group or groups which are now extinct. Such orders would therefore have no near allies in existing orders with an elaborate arrangement of the flower parts.

In Polypetalae, the orders (families) with inferior ovary are placed afterwards, whereas in Gamopetalae they are treated before than those with superior ovary.

In Monocots, much stress is being given to the relative position of the ovary and the perianth characters in determining the affinities, than seems justified by the comparative study of the orders. For example, the families Iridaceae and Amaryllidaceae exhibit greater affinities to Liliaceae than to Scitamineae and Bromeliaceae with which they are allied in this system because of common characters of epigyny.

Thus the treatment of Monocots in general, except for position of Glumaceae is not proper.

Eichier’s System of Classification:

In 1883, a system of classifying the flowering plants was proposed by A.W. Eichler (1839- 1887) is also remarkable because of its resemblance with widely accepted Englerian system.

An outline of Eichier’s system is given below:

A. Cryptogamae:

B. Phanerogamae:

1. Gymnospermae:

2. Angiospermae:

1. Class: Monocotyleae

Series 1. Liliflorae

Series 2. Enantioblastae

Series 3. Spadiciflorae

Series 4. Glumiflorae

Series 5. Scitamineae

Series 6. Gynandrae

Series 7. Helobiae

2. Class: Dicotyleae

Sub-class : Choripetalae

Series 1. Amentaceae

Series 2. Urticineae

Series 3. Polygoninae

Series 4. Centrospermae

Series 5. Polycarpicae

Series 6. Rhoeadinae

Series 7. Cistiflorae

Series 8. Columniferae

Series 9. Gminales

Series 10. Terebinthinae

Series 11. Aesculinae

Series 12. Frangulinae

Series 13. Tricoccae

Series 14. Umbelliflorae

Series 15. Saxifraginae

Series 16. Opuntinae

Series 17. Passiflorinae

Series 18. Myrtiflorae

Series 19. Thymelaeinae

Series 20. Rosiflorae

Series 21. Leguminosae

Anhang : Hysterophyta

Sub-class: Sympetalae

Series 1. Bicomes

Series 2. Primulinae

Series 3. Diospyrinae

Series 4. Contortae

Series 5. Tubiflorae

Series 6. Labiatiflorae

Series 7. Campanulinae

Series 8. Rubiinae

Series 9. Aggregatae

The “series” in Eichler’s system can easily be compared with modem ‘order’ and whereas the ‘orders’ of Eichler’s system may be referred to modem families. The inclusion of the Hysterophyta as an “anhang” in the sub-class Choripetalae is the indication that in those days the position of angiospermic parasites was not at all clear. This group includes Loranthaceae, Rafflesiaceae and the Balanophoraceae.

Eichler also included one non-parasitic family Aristolochiaceae in this group. Eichler’s system also separates the Gymnosperms from their usual position between the Dicotyledons and Monocotyledons (as proposed by Bentham and Hooker) and raised the group to equivalent group with the angiosperms and lower than the monocotyledons.

Engler and Prantl’s System of Classification:

Adolf Engler (1844-1938), a German botanist who served as Professor of botany in the University of Berlin for thirty years and director of Botanical Gardens from 1889 to 1921. His phylogenetic system of classification was first published as a guide to the botanical garden of Breslau in 1892.

Later on the system expanded in a monumental work called “Die Naturlichen Pflanzebfamilien” with means for the identification of the genera of whole plant kingdom.

This publication continued with numerous volumes, many supplements, syllabi and revisions from 1895 to the present day. This system has been the dominant one of the plant classification in most of the scientific world since 1900. Most of the prominent herbaria of the world are arranged according to this system. This great work was completed in the collaboration of his associate worker Eugen Prantl (1849-1893).

According to this system the families were arranged in accord to the increasing complexity of the flower, fruit and seed development.

The general outline of the system proposed by Engler and Prantl is given below:

Merits and Demerits of Engler and Prantl’s System of Classification:

Merits:

According to this system, the large artificial group of Bentham and Hooker’s system, the Monochlamydeae has been completely abolished, and its families have been distributed among the related forms with free petals in the large series of this (Engler’s) system, the Archichlamydeae.

The Sympetalae of this system corresponds to the Gamopetalae of Bentham and Hooker’s system.

In this system the Gymnosperms are treated separately.

The families with inferior ovary have been treated in the last, both in Archichlamydeae and Sympetalae. The advancement is marked from the hypogyny to complete epigyny. Engler considered the orchids to be more highly evolved than the grasses.

Demerits:

In this system the Amentiferae or catkin bearers, (e.g., Salicaceae, Juglandaceae, Betulaceae, etc.) have been regarded as most primitive and precede petaliferous families, (e.g. Ranunculaceae and Magnoliaceae). The Amentiferae are a reduced rather than a primitive group. According to Bessey and others the polypetaly was earlier, and apetaly was derived from it through modification.

The acceptance of the derivation of dichlamydeous flowers (perianth in two series) from monochlamydeous ones (perianth in single series) is objectionable.

The other demerits of this system (Engler’s) are:

Derivation of parietal placentation from axile placentation.

Derivation of free-central placentation from parietal placentation.

Derivation of bisexual flowers from unisexual flowers.

Derivation of entomophily from anemophily.

In this system Monocots have been considered to be more primitive than Dicots, which does not correspond to the present day knowledge.

C.E. Bessey, an American botanist (1845-1915) proposed a system of classification based on Bentham and Hooker’s system. According to Bessey the Ranales were the primitive angiosperms from which two branches were given out which gave birth to Monocots and Dicots. The system proposed by C.E. Bessey has never been accepted and adopted to any great degree in the world.

Richard von Vettstein (1862-1931), an Austrian botanist also proposed a system of classification parallel to Engler and Prantl’s system with minute differences. In this system the unisexual and naked flowers are considered more primitive than bisexual and flowers with perianth. He considered dicots to be more primitive than monocots.

Hans Hallier (1868-1932), a German botanist proposed a system based on phylogenetic relationships parallel to Besseyan system with minor alternations. He considers dicots to be older and more primitive than monocots.

A.B.Rendle (1865-1938), an English botanist has also classified the flowering plants in his two-volumes “The classification of flowering plants”. Vol. I contains Monocots and Vol. 11 contains Dicots. His system resembles Englerian system with very minor differences.

According to him the Dicots are arranged in three grades:

1. Monochlamydeae,

2. Dialypetalae, and

3. Sympetalae.

He considers the family Compositae (Dicot) to be highest evolved.

Oswald Tippo, of the University of Illinois published an outline (1942).of a projected phylogenetic classification. This system, however, was not his original, but was a compilation, a synthesis of several principles of Smith and Eames. The classification of non-vascular plants was that followed by G.M. Smith (1938) and the basic arrangement of vascular plants was that proposed by A.J. Eames (1936).

Tippo studied and synthesised the palaeobotanical data and compared these data with the data obtained through the study of living plants.

He emphasized the dependence on the vegatative characters such as plant form, branching and vascular anatomy in arriving at the natural grouping of major groups. This system emphasises that the Pteridophyta is not a homogeneous group and that there is no distinct line of differentiation between Pteridophyta and Spermatophyta.

The outline of this classification is as follows:

Kingdom: Plantae

Sub-kingdom: Thallophyta hyla.

1. Cyanophyta; 2. Chlorophyta; 3. Chrysophyta; 4. Pyrrophyta; 5. Phaeophyta: 6.Rhodophyta; 7. Schizomycophyta; 8. Myxomycophyta; 9. Eumycophyta.

Sub-kingdom: Embryophyta

Phylum: Bryophyta

Class. 1. Musci; 2. Hepaticae; 3. Anthocerotae

Phylum: Tracheophyta

Sub-phylum: Lycopsida

Class: Lycopodineae

Orders: 1. Lycopodiales; 2. Selaginellales; 3. Lepidodendrales; 4. Pleuromeiales; 5. Isoetales.

Sub-phylum: Sphenopsida.

Class: Equisetineae

Orders: 1. Hyeniales; 2. Sphenophyllales; 3. Equisetales.

Sub-phylum: Pteropsida

Class: Filicineae

Orders: 1. Coenopteridales; 2. Ophioglossales; 3. Marattiales; 4. Filicales

Class: Gymnospermae

Sub-class: Cycadophytae

Orders: 1. Cycadofilicales; 2. Bennettitales; 3. Cycadales.

Sub-class: Coniferophyta

Orders: 1. Cordaitales; 2. Ginkgoales; 3. Coniferales; 4. Gnetales.

Class: Angiospermae

Sub-class: 1. Dicotyledoneae; 2. Monocotyledoneae

John Hutchinson (1884-1972) an English botanist has given the latest information about the phylogenetic classification of angiosperms which has been published in his famous work, “Families of Flowering Plants” recently in 1959.

Formerly this work was published twice in 1926 and 1934. Hutchinson’s classification is more closely related to that of Bentham and Hooker’s and Bessey’s systems of classification than that of Engler and Prantl’s system.

According to Hutchinson, the primitive polypetalous forms have been diverged from the very beginning along two separate lines. One of the lines still retains the arboreal habit whereas the other one has adopted the herbaceous habit. The first order of his arboreal line is Magnoliales and the first order of herbaceous line is Ranales. Hutchinson has divided the angiosperms into two large groups 1. Herbaceae and 2. Lignosae.

The group Herbaceae contains the herbaceous representatives and the group Lignosae contains the woody representatives. He has proposed that the families having apetalous flowers have been derived partly through the Magnoliales and partly through the Ranales.

Hutchinson has divided the seed plants into two phyla:

1. Gymnospermae and 2. Angiospermae. The phylum Angiospermae has been further divided into two sub-phyla-1. Dicotyledones and 2. Monocotyledones.

The sub-phylum Dicotyledones has been divided into two divisions:

1. Lignosae and 2. Herbaceae. The Lignosae, a woody group and Herbaceae, a herbaceous group. The sub-phylum Monocotyledones has been divided into three groups-1. Calyciferae, 2. Corolliferae and 3. Glumiflorae.

The flowers of group Calyciferae possess distinct calyx and corolla; the flowers of group Corolliferae possess more or less similar calyx and corolla; the flowers of group Glumiflorae possess much reduced perianth or lodicules.

Phylum Angiospermae:

Ovules enclosed in an ovary usually crowned by a style and stigma, the latter receiving the pollen grains mainly through the agency of insects becoming wind- pollinated when much reduced. Wood when present consisting of true vessels.

A more recently evolved phylum than the Gymnospermae, and constituting the bulk of the present world vegetation, yielding valuable timbers and practically all food, forage and medicinal plants.

Sub-Phylum I. Dicotyledones-Embryonic plant with two cotyledons. Vascular bundles of the stem usually arranged in a circle (except in a few genera of the lower herbaceous families which have scattered bundles). Leaves typically net veined, opposite or alternate. Flowers usually pentamerous or tetramerous.

Division I. Lignosae-Trees and shrubs and some herbs clearly derived from and related to other woody plants-a fundamentally woody group.

Division II. Herbaceae-Herbs, or rarely shrubby plants related to and derived from herbaceous stocks—a fundamentally herbaceous group.

Sub-Phylum II. Monocotyledones-Embryonic plant with only one cotyledon; vascular bundles of the stem closed and scattered. Leaves typically parallel nerved, alternate, often sheathing at the base. Flowers usually trimerous.

Primitive and advanced characters which formed the basis of his classification are:

Polypetalous condition is more primitive than gamopetalous condition; unisexual flowers are more advanced than bisexual flowers; apetalous forms have originated from petaliferous stock, and represent reduction and advance; free parts on the whole are considered more primitive than connate or adnate parts; thus numerous free stamens are earlier than few or connate stamens; similarly apocarpous pistil is more primitive than syncarpous pistil; spiral arrangement of parts is more primitive than cyclic.

The outline of Hutchinson’s system of classification is as follows:

Merits and Demerits of Hutchinson’s System:

Merits:

1. Most taxonomists are of opinion that this system has given a much better idea of phylogenetic conception and has stimulated phyletic rethinking to a greater extent;

2. Primitive or basic orders are Magnoliales representing arbore-scent families, and Ranales representing herbaceous families, giving rise to woody and herbaceous forms respectively on parallel lines;

3. Bisexual and polypetalous flowers precede unisexual and gamopetalous flowers;

4. Amentiferae(catkin-bearing families with unisexual, apetalous flowers), e.g., Fagaceae-oak, Betulaceae birch, Juglandaceae-walnut, Salicaceae-willow and poplar, etc., is regarded as advanced (and not primitive as considered by Engler) and thus transferred (including Urticales) to a new phyletic position close to Rosales and Leguminales; their apparent simplicity represents reduction and specialization (and not primitiveness);

5. Casuarinaceae has been assigned an advanced position and placed at the top of the Amentiferae;

6. Several big orders have been split up into distinct small families, thus simplifying matters, e.g., Rosales, Parietales, Malvales, etc.;

7. Many families have been raised to the rank of orders, e.g., Leguminosae to Leguminales, Saxifragaceae to Saxifragales, Podostemaceae to Podostemales, etc.;

8. Reshuffling of several orders and families, e.g., Cactales (Opuntiales of Engler) placed close to Cucurbitales and Passiflorales;

9. Origin of monocotyledons from dicotyledons at an early stage of evolution, the point of origin being the Ranales;

10. Splitting up of Helobiae (of Engler) into separate orders and considering the order Butomales (Butomaceae and Hydrocharitaceae) as the starting point of monocotyledons;

11 .Reshuffling of genera of Liliaceae and Amaryllidaceae on the basis of inflorescence characters;

12.Rearrangement of several orders, finally ending in Cyperales and Graminales.

Demerits:

1. Many taxonomists do not agree with his rigid bifurcation of dicotyledons into Lignosae (woody plants) and Herbaceae (herbaceous types);

2. Many taxonomists hold different views regarding the relationship between various orders and families;

3. Monophyletic view regarding the origin of angiosperms is not universally accepted;

4. Monophyletic origin of Monocotyledons from the Ranales, as against the polyphyletic (diphyletic) views of Lotsty (1911) and Hallier (1912);

5. Urticales, Umbellales, Euphorbiales, etc., as originating from different ancestors.

List of Families of Dicotyledones in the Present Text with certain more or less constant characters.

Leaves: Opposite (or verticillate) leaves constant:

Families with constantly opposite (or verticillate) leaves.

Caryophyllaceae; Casuarinaceae; Rubiaceae.

Leaves: Opposite (or verticillate) leaves predominant:

Families in which opposite (or verticillate) leaves are predominant.

Acanthaceae; Apocynaceae; Asclepiadaceae; Loranthaceae; Myrtaceae; Nyctaginaceae; Pedaliaceae; Rutaceae; Scrophulariaceae.

Leaves: Compound: leaves predominant:

Families in which compound leaves are predominant.

Umbelliferae (Apiaceae); Caesalpiniaceae; Papilionaceae (Fabaceae); Mimosaceae; Rosaceae; Rutaceae.

Leaves: Sometimes Compound:

Families in which compound leaves sometimes occur. Convolvulaceae; Cucurbitaceae; Euphorbiaceae; Ranunculaceae; Sterculiaceae; Verbenaceae.

Stipules: Leaves always stipulate:

Stipules are constant in the following families.

Caesalpiniaceae; Papilionaceae (Fabaceae); Magnoliaceae; Malvaceae; Mimosaceae; Polygonaceae; Rubiaceae.

Stipules: Leaves mostly stipulate:

Families in which the leaves are mostly stipulate. Linaceae; Rosaceae; Sterculiaceae.

Glandular Leaves:

Families in which glandular or pellicid dots occur or sometimes occur in the leaves. Acanthaceae; Anacardiaceae; Annonaceae; Asteraceae (Compositae); Combretaceae; Euphorbiaceae; Magnoliaceae; Meliaceae; Myrtaceae; Nymphaeaceae; Piperaceae; Polygonaceae; Rubiaceae; Rutaceae; Urticaceae; Verbenaceae; Violaceae.

Another opening by terminal pores:

Loranthaceae (some); Malvaceae; Solanaceae.

Inferior Ovary:

Apiaceae (Umbelliferae); Asteraceae (Compositae); Cactaceae; Combretaceae; Cucurbitaceae; Loranthaceae; Myrtaceae; Nymphaeaceae (some); Rosaceae (some); Rubiaceae; Saxifragaceae (some).

Current Systems of Classification:

Cronquist’s System:

Arthur Cronquist (1919) of U.S.A. presented a comprehensive system of classification in 1968 and thereafter its revised version in 1981. His system is parallel to that of Takhtajan’s system in so many respects.

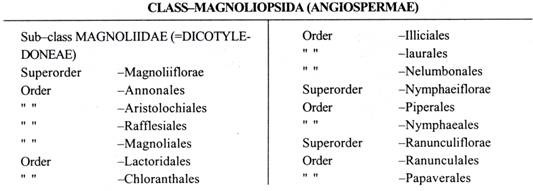

He divided the angiosperms in two classes-Magnoliopsida (=Dicotyledons) and Liliopsida (=Monocotyledons). Magnoliopsida is further divided into six sub-classes, viz., Magnoliidae, Hamamelidae, Caryophyllidae, Dilleniidae, Rosidae and Asteridae; Liliopsida has five subclasses, viz., Alismatidae, Arecidae, Commelinidae, Zingiberidae and Liliidae.

The division Magnoliophyta has two classes, viz., Magnoliopsida (= Dicotyledons) and Liliopsida (= Monocotyledons). There are six sub-classes, sixty four orders, 318 families, and about 165,000 species in Magnoliopsida (=Dicotyledons) whereas in Liliopsida (= Monocotyledons) there are five sub-classes, nineteen orders, 65 families and about 50,000 species.

The outline of Cronquist’s (1981) system of classification is as follows:

Takhtajan’s System:

Armen Takhtajan, an academician of Leningrad, Russia, presented a system of classification of angiosperms for the first time in 1942, and thereafter its revised versions in 1954, 1966, 1969 and 1980 respectively. Takhtajan’s approach is quite similar to that of Cronquist. According to him the angiosperms are of monophyletic origin and evolved from some ancient group of gymnosperms.

The evolutionary tendencies followed by Takhtajan are as follows:

Woody plants precede herbaceous plants.

Sparingly branched trees gave rise to the trees with numerous slender branches.

Evergreen trees precede deciduous woody plants.

Simple pinnately-nerved leaves precede pinnately lobed, pinnatifid and pinnatisect leaves with pinnate venation.

Simple leaves precede compound leaves and vice versa.

Pinnate venation precedes palmate venation. Reticulate venation precedes parallel venation.

Alternate leaf arrangement precedes opposite and verticillaster arrangements.

Stomata with subsidiary cells are primitive and without subsidiary cells are advanced.

Tripentalacunar type of nodal structure is primitive, and unilacunar type is advanced.

The vessel members with scalariform perforations precede the vessel members with simple perforations.

Tracheids gave rise to fibre tracheids, and then to libriform fibres.

Cymose inflorescence is primitive, and racemose is derived one.

Primitive flowers are spiral whereas advanced are cyclic in arrangement of their floral organs.

The primitive stamens were leaf-like, and with marginally situated microsporangia.

The pollen is derived from monocolpate to tricolpate and from tricolpate to triporate. The exine of primitive pollen was without external sculpturing whereas in advanced pollen there was sculpturing of various types.

Apocarpy precedes syncarpy.

Bitegmic ovules are primitive, whereas unitegmic are advanced.

Crassinucellate ovules precede tenuinucellate ovules. Anatropous ovule is primitive; the other types are derived from it.

Entomophily gave rise to anemophily and vice versa.

Polygonum-type of embryo sac is primitive, the other types are derived from it.

Endospermic seeds are primitive, whereas non-endospermic seeds are advanced. The monocot embryo is evolved from dicot embryo.

Many seeded follicle is most primitive type of fruit, from this other types are evolved.

Takhtajan has divided his Division-Magnoliophyta (=Angiospermae) into two classes- Magnoliopsida (= Dicotyledones) and Liliopsida (=Monocotyledones). He has further

divided-Class Magnoliopsida into seven sub-classes and twenty superorders, and Liliopsida into three sub-classes and eight superorders.

According to him the order Magnoliales is most primitive among the flowering plants. All other angiosperms have been derived from the Magnoliales.

The order Alismatales has been supposed to be most primitive among monocotyledons and the members of the other monocotyledonous orders have been derived from them.

According to him the highest evolved order among dicotyledons is Asterales; and Arales among monocotyledons.

The outline of Takhtajan’s (1980) system is as follows:

Dahlgren’s System:

Rolf Dahlgren, a botanist of Copenhagen, Denmark published a system of classification of angiosperms in 1975, and thereafter a revised and improved version in 1980, 1981 and 1983 respectively. He has taken into consideration the utmost possible information.

He has taken into consideration the following:

apocarpy, syncarpy, and monocarpy; choripetaly and sympetaly; monoaperturate pollen grains; sclereid idioblasts; microsporogenesis types; bi-and unitegmic ovules, tenuinucellate, pseudocrassinucellate and crassinucellate ovules; bi-and trinucleate pollens; oxalate raphides, silica bodies; iridoid compounds; ellagic acid and ellagitannins; benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, tropane alkaloids, pyrrolizidine alkaloids; polyacetylene and several flavonoids.

This shows that Dahlgren has used chemical characters extensively in his system of classification.

According to him the angiosperms have evolved in one particular line of gymnosperms and thus treated of monophyletic origin. He is not of opinion that Alimatiflorae are closely connected with the monocotyledonous ancestors.

According to him “the appearance of the monocotyledons may have its counterpart in the evolution of the mainly herbaceous Aristolochiaceae, which also evolved out of early Magnoliales with trimerous flowers and two perianth whorls Aristolochiaceae share with the monocotyledons in possession of cuneate crystalloids in the sieve element plastids.”

According to him the “Amentiferae” have been interpreted as derived from trimerous ancestral type.

Dahlgren is in agreement that the discontinuity between monocotyledons and dicotyledons is not particularly marked. He is of opinion that the monocotyledons can be clearly circumscribed on the combination of a single-cotyledoned embryo and sieve element plastids. This system has also been advocated by serological studies. In Dahlgren’s classification the angiosperms are made up of a class, Magnoliopsida.

It is as follows:

The superorder’s end with the suffix-florae.

According to Dahlgren the superorder magnoliiflorae have been treated to be most primitive among dicotyledons.

They possess the following characters woody habit, primitive wood; P-type plastids in the sieve elements; alternate, exstipulate leaves, cells with essential oils in leaves; benzylisoquinoline alkaloid present, trimerous tepals; flat and leaf-like stamens with sporangia below the apex, pollengrains sulcate, 2-nucleate; gynoecium apocarpous, or monocarpellary; endosperm formation cellular.

The order Nelumbonales is included in superorder Magnoliiflorae and not in Ranunculiflorae.

The superorder Alismatiflorae has the following characteristics which are generally unusual for monocotyledons:

Intervaginal squamules present; vessels absent in the stem and often in the roots; root hairs attached to short epidermal hairs, amoeboid tapetum; 3-nucleate pollen grains; apocarpous or monocarpellary condition of gynoecia; embryo formation of caryophyllad type; oxalate raphides and silica crystals absent.

The outline classification is as follows:

Thome’s System:

Robert F. Thome of California U.S.A., published a system of classification in 1968. Thereafter a revised outline of this system was published in 1981 and 1983 respectively. This system has been used to express the phylogenetic relationships among the higher taxa of flowering plants. The modem trends of taxonomy have been taken into consideration in the depiction of more accurate relationships of different taxa.

He has laid much emphasis on phytochemical approach. The other modern approaches such as palynology, seed morphology, anatomy, embryology, host-parasite relationships, plant geography, paleobotany, microstructure and cytology have been utilized in the differentiation of taxa. According to Thome the Angiospermae are monophyletic in origin.

He has divided the flowering plants into two sub-classes (1) Dicotyledoneae (Annonidae) and (2) Monocotyledoneae (Liliidae). There are 19 superorders in Dicotyledoneae and 9 superorders in Monocotyledoneae.

The outline of Thome’s system is as follows: