Do you want to create an amazing science fair project on horses. you are in the right place. Read the below given article to get a complete idea on horses:- 1. Introduction to Origin of Horses 2. Biological Organisation of Modern Horses 3. Ancestry 4. Biological Trends 5. Palaeontological Procession 6. Triumph 7. Phylogeny 8. Study of Allometry.

Contents:

- Science Fair Project on Introduction to Origin of Horses

- Science Fair Project on the Biological Organisation of Modern Horses

- Science Fair Project on the Ancestry of Horses

- Science Fair Project on the Biological Trends of Horse Evolution

- Science Fair Project on the Palaeontological Procession of Horses

- Science Fair Project on the Triumph of Modern Horses

- Science Fair Project on the Phylogeny of Horses

- Science Fair Project on Study of Allometry in the Evolution of Horses

Science Fair Project # 1. Introduction to Origin of Horses:

The origin and evolution of horses signify the most speculative success of a race in course of its phylogenetic development. Evidences advanced by the fossils in the pages of the earth’s history give a complete and convincing documentary record of the evolution of horses.

The records of the horses go back all the way with successive links from Eocene to the recent time and afford a sound basis of descend with modifications of the train of life.

For better, understanding of the evolution of horses, a brief review of the biological organisation of the modern horses, and their diversifications will be discussed first, then we will analyse the fossil records to ascertain what can be demonstrated about evolution.

Science Fair Project # 2. Biological Organisation of Modern Horses:

Modern horses have reached the highest grade of cursorial adaptation. The whole of structural organisation of horses is due to the perfection of food-getting mechanism and the attainment of speed. The modern horses show considerable genetical diversity.

To offer least possible resistance, the body, neck and head are smoothly rounded and stream-lined. There is no extra projection which can obstruct the attainment of speed.

The limbs exhibit adaptation for speed. Only the third digit of the limb is developed and covered with hoof. The metapodials of second and fourth digits are present as small splint- bones. The distal segment of the limb becomes lengthened by the elongation of the bones. Presence of a cannon bone is a characteristic feature.

The limb joints are of the tongue and groove variety and the movement is restricted to the force-and- aft plane. With the lengthening of limbs, the neck and skull have become very much elongated. The skull has a spacious and well-developed brain-case.

The facial portion is elongated. The orbits are completely surrounded by bone. There is a general tendency towards reduction of teeth. The canines are rarely developed in females. The premolars are becoming molarised. The molars are deep-crowned.

Science Fair Project # 3. Ancestry of Horses:

Piercing the gloomy curtain of geological history many Eocene horses have been recorded which show the dawn of equine evolution.

Eohippus stamps the most primitive horse-like form:

In the lower Eocene bed of North America, Eohippus was the first recorded fossil form which showed equine adaptation. It was a four-toed form. The forelimb had four complete toes and each terminates in a hoof-like nail. There was no trace of pollex. But the hind-limb had three digits with vestigial remnants of the first and fifth digits.

The ulna and fibula were slender bones. The size was smaller and attained about twelve inches in height, but several species may exceed the limit. The premolars were becoming molarised. Modern researches tried to establish the fact that the Eohippus is the direct source from which different forms of horses evolved in time and space.

Science Fair Project # 4. Biological Trends of Horse Evolution:

Starting from the lower Eocene Eohippus upto the modern horses, a great number of fossil stages have been recorded.

A survey of the paleontological record shows the following changes that may be listed as:

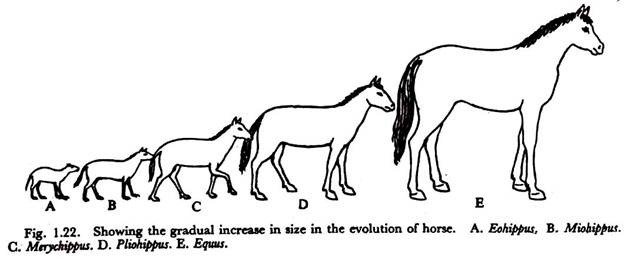

(a) Gradual increase in size from catlike Eohippus to modern horses (Fig. 1.22).

(b) Concurrently with the lengthening of limbs, the neck and the skull become elongated.

(c) Conversion of foot posture from semi-plantigrade to unguligrade.

(d) Gradual loss of digits from five to one.

(e) Attainment and perfection of hoof.

(f) Gradual reduction of ulna and fibula, formation of cannon bone.

(g) Limitation of movement of limbs.

(h) The teeth become elongated and attain complexifies. Gradual loss in the number of teeth.

(i) Pre-molars are gradually becoming molari-form.

Science Fair Project # 5. Palaeontological Procession of Horses:

The fossil remains of horses have been recorded with considerable accuracy and the series can be constructed with completeness from Eohippus to Equus (Fig. 1.23). The pathway of evolution sometimes becomes confusing due to the presence of certain divergent lines. The side-lines are so numerous that they cast doubt on the concept of single and uniform trends in equine evolution.

The evolutionary sequence of equine evolution becomes further complicated by the migratory power of the race. It is believed that the main course of the evolution of horses occurred in North America with migration at various times to the Old world and South America.

Eocene—The epoch of four-toed horse:

Several forms of horses have been recorded in Eocene period. Amongst the Eocene horses Eohippus is regarded as the dawn horse.

Eohippus—the lower Eocene form:

The equine characters of the Eohippus have been discussed previously and this form represents a typical Eocene form. The other forms of the horses recorded in the Eocene period are the Orohippus and the Epihippus. These two forms show little difference from the Eohippus excepting certain features in the nature of dentition.

Orohippus—the middle Eocene form:

The next stage of the equine evolution beyond the Eohippus is the Orohippus. This form showed some advancement over the Eohippus as indicated by the loss of the splint of the fifth digit in the foot. The middle finger of the forelimb becomes slightly increased in size and the outer fingers become much shortened. The third and fourth premolars are becoming molariform.

Epihippus—the upper Eocene form:

This form is further developed than the previous forms where the third and the fourth premolars become completely molariform. According to many, Epihippus may not stand as the direct ancestor of Oligocene horses.

The outermost digits in the forelimb become much diminished and in the hindlimb the middle digit becomes dominant. The Eocene horses are small in size but they show a gradual increase in size. Distribution of Eocene horses from Europe to New Mexico reveals their power of migration.

Oligocene—the epoch of three-toed horses:

Beyond the Eocene forms, the Oligocene horses show further advancement towards equine evolution. The Oligocene horses had to confront many adverse conditions and they have given origin to some divergent forms. Two distinct forms are recognised.

Mesohippus—the lower and middle Oligocene form:

This form attains a size of about 24 inches in height and possesses three functional digits both in the fore- and hindlimbs. The middle digit becomes much elongated. The ulna and fibula are slender bones. All the premolars excepting the first one become molariform.

Miohippus—the upper Oligocene form:

This form basically resembles the Mesohippus in all respects except that the size is larger.

Miocene—the epoch of diversification:

With the advent of Miocene period there was extensive branching out of horses towards several lines. Miocene horses were of several forms and exhibit at least three adaptive lines. Of the three evolutionary lines, two overcome the evolutionary hurdles and the other line became extinct.

Parahippus—the lower Miocene horse:

This form represents the transitional stage. In this stage the valleys between the crests in the teeth started to become filled up with cement. The lateral toes are much reduced.

Merychippus—the middle Miocene horse:

This form holds the key of the direct line of equine evolution. The teeth showed a transition from the uncemented short- crowned forms to the fully cemented long- crowned forms.

Though this form is morphologically three-toed, but functionally they are one-toed. The orbit, for the first time, was almost complete. In Merychippus the milk set was uncemented and short- crowned but the permanent set was long- crowned and cemented.

Protohippus—the upper Miocene form:

This form evolved from the Merychippus but showed certain advancement in that both the milk set as well as the permanent set were long-crowned and cemented. The limbs were still three- toed. Evolutionary sidelines.

During Miocene there were two evolutionary sidelines. Hypohippus. This form had low-crowned teeth suited for browsing on succulent herbs. They were called as the browsing horses. Like all other Miocene horses the limbs were three-toed.

They attained the size of pony and were doomed to racial extinction. Hipparion. They showed certain progressive features than the previous forms. Perfection of teeth and development of special features in the skull were progressive in nature.

But they were conservative in retaining three toes in the limbs. They continued up to the Pliocene time when they became all extinct excepting few forms who struggled upto the early Pliestocene period.

Pliocene—witnessed the rise of one-toed true horses:

Pliocene period was geologically of great unrest. Pliohippus originated from the Protohippus in the upper Miocene period. They were very progressive forms. The development of the skull characteristics and the perfection of the teeth were like modern horses.

They were single toed forms and there was almost no trace of the lateral toes. Plesippus. This form arose in the late Pliocene period and attained the size of the Arab horse but the limbs were much smaller. They were one-toed forms with no trace of lateral digits. The skull was Equine-like. The dental pattern was more advanced than that of Pliohippus and the teeth were as in Equus.

During the Pliocene period another notable form was the South American form— the Hippidion, a derivative of the Protohippus. The limbs were one-Toed, but were very stout rather than slender. The Hippidion continued in the Pleistocene period and transformed into the Orohippidium.

Science Fair Project # 6. Triumph of Modern Horses:

The modern horses belong to the genus Equus. Both in North and South America a large number of extinct species of Equus belonging to Pleistocene period were recorded. Several forms of horse-like animals are still surviving to-day in Africa and Asia. The forms present in Europe and America are either feral or domesticated. The modern forms of horses belonging to the genus Equus are the descendant from the Plesippus.

The original site of the origin and evolution of the horses is North America, where they were plenty but became extinct in Pleistocene time. At the beginning of Pleistocene time, Equus had migrated from the original North American home to the other continents to become world-wide. In the modern time a number of forms commonly designated as the horses, Zebras and asses are present in the old world.

Science Fair Project # 7. Phylogeny of Horses:

The phylogenetic sequences of horses are mostly uni-directional with few side-lines. Fig. 1.24 shows the phylogenetic tree of horses.

Science Fair Project # 8. Study of Allometry in the Evolution of Horses:

Serious attempts have recently been made to estimate the rate of evolutionary changes occurred in the phylogenetic history of an animal. Many of the evolutionary changes encountered in an animal are measurable changes in proportions. This phenomenon is vividly observed in the evolution of horses. The present-day horse, Equus is certainly a different creature from Eohippus.

Despite this fact, the differences observed in the evolutionary steps from Eohippus to Equus are the consequences of the increase in size. So if a particular structure or organ grows relatively slower or faster than the body as a whole, it is expected that the proportion will differ in animals differing in adult size. If a particular organ becomes larger in larger animals this is said to be positively allometric.

Increase in the length of the facial portion of the skull furnishes an instance of positive allometry. It has also been advocated that the increase in the length of facial portion between embryos to adult bears a close parallelism of the changes occurred from Eohippus to Equus. If an organ or structure becomes smaller in larger animals, this is called as the negatively allometric.

Reduction of lateral toes in the limbs in the evolution of horses shows the example of negative allometry, because the lateral toes are relatively smaller in larger animals. Although the underlying principles on such laws have been questioned by many, this demonstration showed that growth actually follows certain laws; especially in the evolution of horses it is true.

Place of origin:

The earliest known fossil horse, Eohippus, has been recorded in North America. Fossil horses have been recorded scatteredly in Europe and Asia, but the sequences are not so complete as we see in North American fossils. From the completeness of the fossil records, North America is regarded as the place of equine origin and the Old world forms were the representatives of the genera migrated from North America.

General considerations:

The study of fossil records of horses makes it convincing that evolution has progressed by gradual change. The evolutionary line is more or less complete, but the lack of intermediate forms in regions other than North America makes many European Palaeontologists to think that the evolution has occurred by jumps and saltation.

It is the general belief that the evolution of horse has been directed along a single direction and shows an instance of Orthogenesis’. But such assumption leads to much confusion in explaining the side-lines of evolution. It is to be remembered that not all the evolutionary lines progressed in the same direction. It is a fact that some of the evolutionary lines progressed in one direction for a long time.

This is probably possible through ‘Orthoselection’ which select all those genetic factors that cause the success in one particular environment by a particular make-up and thus produce evolutionary changes in one direction.

The course of equine evolution reveals a unique example of the evolutionary train of species from Eocene to the recent time. Of all the evolutionary histories of animals, none is so vividly known as that of the horses. The excellent array of fossils gives a remarkable progressive record in time and space.