In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Definition of Adventitious Root System 2. Typical Adventitious Roots 3. Modification.

Definition of Adventitious Root System:

Roots that grow from any part of plant other than the radicle or its branches are called adventitious roots (L. adventitious— extraordinary). They branch like the tap root. A mass of adventitious roots along with their branches constitute an adventitious root system. Adventitious root system may be underground or aerial. They generally develop from stem nodes, intermodals, leaves, etc.

Horizontal stem of creepers often develop adventitious roots from the nodes (e.g., Grass, Wood Sorrel). Branch cuttings and leaf cuttings (e.g., Rose, Sugarcane, Tapicca, Sansiviena) develop adventitious roots when placed in soil. In Coleus, the cuttings develop adventitious roots on being partially immersed in water. Hormones also induce development of adventitious roots.

Typical Adventitious Roots:

Fibrous Roots:

They are underground roots which arise in groups from the nodes of an horizontal stem (e.g., Grass, Fig. 5.10). The main roots are of equal length. They give off small branches. Both the main root and their branches are thin and thread-like. Therefore, they are called fibrous roots. The fibrous roots do not penetrate deep in the soil. They remain near the soil surface and are called surface feeders.

Modifications of Adventitious Roots:

Storage of Food:

1. Fleshy Adventitious Roots:

The adventitious roots become thick and fleshy due to the storage of food.

They are of several types depending upon the shape and place of the swollen part:

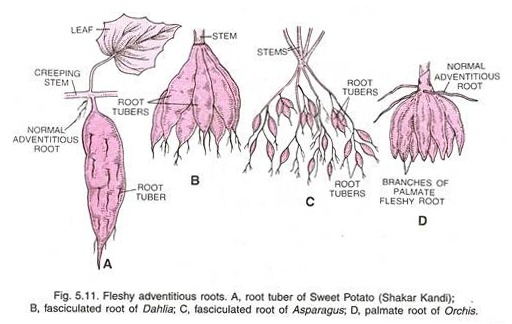

(i) Tuberous Root or Single Root Tubers:

The swollen roots do not assume a definite shape. They occur singly, e.g., Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas, vern. Shakar Kandi, Fig. 5.11 A).

(ii) Fasciculated Fleshy Roots:

The swollen roots or root tubers occur in clusters. In Dahlia they lie at the base of the stem (Fig. 5.11 B) while in Asparagus the fasciculated fleshy roots occur at intervals on the normal roots (Fig. 5.11 C).

(iii) Palmate Roots:

The fleshy roots are thickened like the palm of human hand. They similarly possess finger-like outgrowths, e.g., Orchis (Fig. 5.11 D).

(iv) Nodulose Roots:

In nodulose roots the swellings occur only near the tips, e.g., Curcuma amada (Mango Ginger, Fig. 5.12 A), Maranta (Arrow-root), Turmeric.

(v) Moniliform or Beaded Roots:

The roots are swollen at regular intervals like beads of a necklace, e.g., Basella (Portulaca) rubra (Indian Spinach, vern. Kulfa), Momordica (Fig. 5.12 B), some grasses (Fig. 5.12 C).

(vi) Annulated Roots:

These thickened roots possess a series of ring-like outgrowths or swellings, e.g., Cephaelis or Psychotria (Ipecac, Fig. 5.12 D).

Mechanical Support:

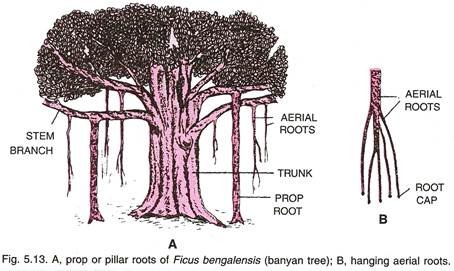

2. Prop or pillar (Fig. 5.13):

They are thick pillar-like adventitious roots which grow from and support heavy horizontal branches of Banyan tree. Initially the roots are aerial and hygroscopic. They become red in the moistened state. Root caps are present at their tips.

As the roots reach the soil, they become thick and pillar-like. The main trunk of the tree often becomes indistinguishable. Its death will not affect the growth of the tree because the crown is supported and nourished by prop roots.

A Banyan tree (Great Banyan Tree) growing in Indian Botanic Gardens, Howrah (Indian Botanical Gardens, Kolkata) has 1775 prop roots. Its main trunk has decayed. The crown of the tree has a circumference of 404 m.

The tree is over 200 years old. The largest Banyan tree grows in Thimmamma Marrimanu village of Anantapur district in Andhra Pradesh. It is spread over an area of 5.2 acres. Two other famous trees are at Adayer (=Adiyar) in Chennai and Ketohalli village near Bangalore. Rhizophora a mangrove plant also possesses prop roots on which lenticels occur.

3. Stilt Roots (Brace Roots):

They are short but thick supporting roots which develop obliquely from the basal nodes of the stem. In Sugarcane, Maize, Pennisetum and Sorghum the stilt roots grow in whorls. After penetrating the soil, they develop fibrous roots which hold the soil firmly to provide support to the long and narrow jointed and unbranched stems (culms) like the ropes of pole or tent (Fig. 5.14).

Additionally they allow for better absorption of water and mineral salts. In Screwpine or Pandanus odoratissimus the stilt roots develop only from the lower surface of the oblique stem to provide support. Being one sided, they are also called prop roots. The supporting roots of Pandanus bear much folded multiple root caps (Fig. 5.15).

4. Clinging or Climbing Roots:

These are non-absorptive adventitious roots which are found in climbers. They may arise from the nodes (e.g., Tecoma, Betel), intemodes (Ficus pumila) or both (e.g., Ivy). The clinging roots penetrate the cracks or fissures of the support.

They hold the support firmly by forming claws (e.g., Tecoma), swollen discs or secreting a sticky juice at their tips (e.g., Ivy). Examples are found in juvenile stage of Ivy (Hedera nepalensis, Fig. 5.16A), Pothos (Money Plant, Fig. 5.16 C), and Betel (vern. Paan, Piper. Floating betle, Fig. 5.16 B), Black Pepper (Piper nigrum), Tecoma (Fig. 5.16 D).

Vital Functions

5. Assimilatory Roots:

They are green roots which are capable of photosynthesis. In Trapa (Water Chestnut, vern. Sanghara, Fig. 5.17) the green assimilatory roots are submerged like other roots.

They develop from the stem nodes and are highly branched to increase photosynthetic area. Photosynthetic roots are also found in Tinospora (vern. Gilo, Gillow, Gurcha, Fig. 5.18). They are like green hanging threads which arise from the stem nodes during the rainy seasons and shrivel during drought.

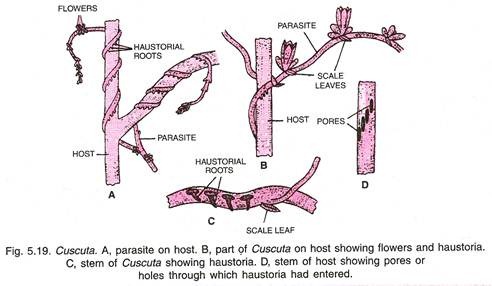

6. Haustorial or Parasitic Roots:

The roots occur in parasites for absorbing nourishment from the host. Hence, they are also called sucking roots or suckers. Cuscuta (Dodder, vem. Amarbel or Akashbel, Fig. 5.19) has nongreen stems and scale leaves. It does not have any connection with the soil. The parasite sends haustorial roots into the host (e.g., Duranta, Zizyphus, Citrus, Acacia, Clerodendrum).

They make connections with both xylem (water channel) and phloem (food channel) of the host absorbing both water and food (Fig. 5.20). The partial parasite of Viscum (Mistletoe) is green. It sends a primary haustorium into the host from which secondary haustoria arise making connections with the xylem channels of the host for absorbing water and mineral salts only.

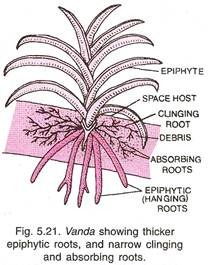

7. Epiphytic or Aerial Roots (Hygroscopic Roots, Fig. 5.21):

The roots occur in epiphytes (plants living on the surface of other plants for shelter and space only; hence also called space parasites). Epiphytes bear three types of roots — clinging (for fixation), absorbing (for absorbing mineral salts and moisture from dust collected on bark) and hygroscopic aerial or epiphytic.

The aerial or epiphytic roots are thick, irregular and hang down in the air. They do not have root caps and root hair. Instead they possess a covering of dead spongy tissue known as velamen. With the help of velamen, the epiphytic roots are able to absorb water from moist atmosphere, dew and rain, e.g., Vanda, Dendrobium.

8. Floating Roots (Root Floats, Fig. 5.22):

They occur in Jussiaea (= Ludwigia). Here a number of adventitious roots arise from each node. Some of them store air, become inflated, project out of water, make the plant light and function as floats. The root floats help the plant in floating on the surface of water. They also help in gaseous exchange (hence also respiratory roots).

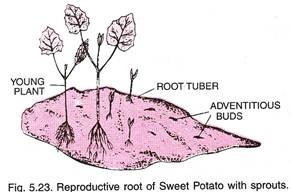

9. Reproductive Roots:

These adventitious roots are generally fleshy and develop adventitious buds. The adventitious buds can grow into new plants under favourable conditions. Such roots are called reproductive roots, e.g., Sweet Potato (vern. Shakar Kandi, Fig. 5.23), Dahlia.