An Overview of Secretory Tissues (With Diagram)!

The cells directly concerned with secretions like resins, essential oils, mucilage, latex and similar substances together constitute secretory or special tissues.

These cells have neither common origin nor morphological continuity. They may occur as isolated patches in any part of the plant, or may form well-organized structures.

Two types of cells are usually found in this tissue. In some of them the materials formed are exuded from the cells. Nectaries (Fig. 547A) exuding sugary fluids are the examples. These are also called excretory cells. In others the materials formed remain stored up in the cells to be released only after the breakdown of the cells.

The cells belonging to the first type have rich cytoplasm and prominent nuclei, whereas those of the second type are large cells with well-developed cavity where the secretion remains stored up. The ducts containing essential oils and mucilage are the examples.

Glands:

Glands are well-organized secretory structures, composed of diverse types of cells. The secretory materials are produced and liberated by the protoplasts of the cells. The substances may be at once exuded from the seats of formation as in nectaries, or they may remain stored in some cavity inside.

The glands may be external or superficial, naturally formed on the epidermis; or they may be internal where the cavities correspond to the intercellular spaces formed either schizogenously or lysigenously.

Glandular hairs and trichomes, common in many plants are superficial in origin. The common glands are those which secrete digestive enzymes, known as digestive glands, nectar-secreting ones or nectaries, and, similarly, resin ducts, oil ducts, latex-secreting glands called laticiferous ducts, and water- secreting ones called hydathodes.

Digestive Glands:

It is an established fact that plants in general have intracellular digestion. Here the living cells secrete enzymes, no specialised structure being present for the purpose. The insectivorous plants possess special digestive glands which secrete proteolytic (protein-digesting) enzymes and thus part of the nitrogen requirement is obtained from the bodies of the insects they catch. So it is a case of extracellular digestion.

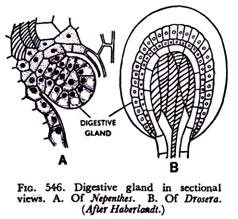

In Drosera or sundew the gland (Fig. 546B) is located at the tip of the tentacle; in Nepenthes, the pitcher plant, glands (Fig. 546A) occur along the wall of the pitcher and secrete enzyme in the liquid present inside the pitcher. In Dionoea (Fig. 23) the glands are normally inactive, but contact with the insect-body stimulates them.

Nectaries:

These are special glands usually located on the floral parts. They secrete the sugary substance, nectar or honey, and thus attract the pollinating insects. These glands are superficial, usually consisting of epidermal cells.

In some cases the cells forming the glands are columnar or papillose ones (Fig. 547A), with dense protoplast, whereas in others the secretory cells may be more or less like normal epidermal cells, but without cuticle.

Nectar is exuded through the walls and exposed on the outer surface of the gland. Nectaries may also occur on purely vegetative parts, in that case they are called extra-floral nectaries.

Those present on the rim of the pitcher of Nepenthes which really lure the poor insects, and those occurring on the stipules of Vicia spp. (Fig. 547B) of family Leguminosae, are nice examples of extra- floral nectaries.

Resin Ducts and Oil Ducts:

Substances like resins, oils, gums are copiously secreted in gymnosperms in general and also in many angiosperms. The materials are secreted and conducted through special glands, which are also called ducts.

In gymnosperms like pine these ducts form extensive canals occurring in vertical and horizontal position. But ducts present in the fruits of umbellifers are localised in certain regions. The resin ducts are formed schizogenously and appear as tube-like bodies having a lining of small parenchyma cells with dense protoplast (Fig. 518A). The latter are called epithelial cells which excrete resin.

The oil ducts of umbellifers, though localised and limited in extent, are also formed in the same manner. The characteristic oil glands present on the rinds of citrus fruits like lemons and oranges are formed lysigenously. The cavities remain filled tip with essential oils and other substances due to disorganization of tissues (Fig. 518B).

Laticiferous Ducts:

Long tube-like bodies containing the viscous fluid, latex, occur in a large number of angiospermic families. These are called laticiferous ducts or tubes. Latex is usually a milky, often yellowish or watery fluid, which is readily exuded when the plants containing it are injured.

It is an emulsion of various substances like proteins, sugars, enzymes, rubber, etc., in a watery matrix. Latex is secreted by the cells and conducted through them often forming extensive system inside the plant body. The commercial value of latex has already been reported. Latex of Hevea of family Euphorbiaceae and some other allied plants is the chief commercial source of rubber, and that of papaw contains the very useful enzyme papain, and Papaver, a useful alkaloid.

From ontogenetic point of view laticiferous ducts are of two types, viz., non-articulate latex ducts or latex cells and articulate latex ducts or latex vessels. They are also called simple and compound laticifers respectively. There is no difference between the two, so far as the contents are concerned.

Non-articulate latex ducts or latex cells (Fig. 548A), are single cells. They arise as small meristematic cells at the very embryonic stage. With the growth of the plants these cells also elongate and make their way through other tissues.

The growth of the tip is mainly apical and often branches are given out. Thus as much elongate tube-like bodies growing continuously they penetrate into all the tissues of the plant, even invading the newly-formed organs like leaves, buds and lateral roots.

The latex cells are coenocytic (multinucleate) bodies with scanty cytoplasm. They do not form a network. This type of latex duct is common in members of families” Asclepiada- ceae, Apocynaceae, Euphorbiaceae, etc.

In some plants like Vinca of family Apocynaceae and some members of Urticaceae the latex cells remain unbranched. The cells here originate not in the embryo, but in meristem of developing shoot. But instead of extending like ones previously discussed, these cells remain restricted to one internode and to the attached leaf and branch.

Articulate latex ducts or latex vessels (Fig. 548B) originate from a row of cells in continuous series by partial or total dissolution of the end-walls. So from ontogenetic point of view it is a compound structure resembling a Xylem vessel.

But the latex vessel is living and coenocytic. The rows of cells may be even irregular. The ducts send out branches frequently, which extensively penetrate through other tissues and eventually form a complex system of network. Like non-articulate ones this type also originates in the early embryonic stage where fusion of cells has been observed.

Latex vessels occur in poppy of family Papaveraceae, papaw of Caricaceae, banana of Musaceae and the rubber-yielding plant Hevea of family Euphorbiaceae. It is interesting to note that the nature of duct does not bear any relation with the systematic position of plants. Most of the plants of family Euphorbiaceae possess latex cells, but Hevea, the most important rubber-yielding plant of the same family has latex vessels.

Hydathodes:

These are specialised structures present in many angiosperms, through which exudation of water takes place. So they are also called water-stomata or water- pores. Exudation or guttation is the process of escape of water in liquid form.

It occurs in humid climates when there is rapid absorption of water by roots, but transpiration rates are reduced. On cool nights following sultry days water is found at the tips and margins of leaves of many plants in form of dew-drops. Every drop marks the location of a hydathode through which water has come out.

In many plants like Tropaeolum (garden nasturtium), tomato, hydathode is not a simple pore. Here the ends of vascular elements, the tracheids, are in contact with some loosely arranged cells, called epithem, which possess scanty chlorophyll. External to epithem there is a cavity and, finally, the pore.

The whole structure is referred to as hydathode (Figs. 549 & 550). These pores or stomata differ from ordinary stomata of the leaves in a number of points, viz., they are larger in size, are located at the vein-endings, and particularly in the fact that they always remain

open, the characteristic mechanism of opening and closing of ordinary stomata being absent.

In some plants the epithem may be lacking, where water moves to the pore through the mesophyll cells, Morphologically hydathodes may be compared to the stomata. These are the passages for exudation of water, often with some dissolved salts, particularly occurring in the plants of humid climate.