In this article we will discuss about the History and Rules of International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN).

History of ICBN:

Before the middle of the 18th century, plant names were usually polynomials i.e. made up of several words in a series. It was superseded by the binomial system, which was first applied for the plant kingdom by Linnaeus in his Species Planetarium. It was Linnaeus who proposed the elementary rules of naming plants first in 1737 in his Critica botanica and then in 1751 in Philosophia Botanica.

Elementary rules were framed to serve as a guide to botanists. Later in 1813, A.P. de Candolle in his Theories elementary de la botanique gave a detailed set of rules regarding plant nomenclature.

However discovery of new plants from later explorations caused concern over procedures for naming these species. Thus, with the passage of time, the need for an international system and rule for naming plants became increasing apparent.

It was then that Alphonse de Candolle, son of A.P. de Candolle convened an assembly of botanists of several countries to present a new set of rules. Candolle convened the First International Botanical Congress held at Paris in 1867.

Subsequent meetings of the International Botanical Congress were held in 1892 (Rochester Code), 1905 (Vienna Code), 1907 (American Code) and 1910, but a general agreement regarding the internationally acceptable rules of plant nomenclature was reached in 1930 at the IBC meeting at Cambridge where for the first time in botanical history, a code of nomenclature came into being that was international in function as well as in name.

This code is called the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN). The modifications or amendments as suggested by the International Botanical Congress at the subsequent meetings have been incorporated in the ICBN on a regular basis.

(i) Paris Code (1867):

The First International Botanical Congress was held at Paris in August, 1867, and was aimed at the standardization and legislation of proper nomenclature practices. About 150 American and European botanists were invited to attend the congress.

It was resolved that the Laws, as adopted by the Assembly, shall be recommended as the best Guide for Nomenclature in the Vegetable Kingdom. These Laws were called the Paris Code, as they were adopted at the French capital, or de Candolle rules, as they were prepared by Alphonse de Candolle. According to the Paris Code, the starting-point for all nomenclature was fixed with Linnaeus.

However no date or any work was specified. The rule of priority was considered as basic with no provisions for exceptions. It was very important that the publication be valid and attention was given to author citation and terms applied to categories of plants. Although the Paris Code guided taxonomic activity in most countries to a considerable degree, but their application showed many inherent defects.

As time went on, American and British botanists deviated from the rules and they started practicing the unwritten law named Kew Rule according to which if a species was transferred to another genus, the specific epithet need not be transferred to the new genus but the author was free to use a new epithet in the new combination.

(ii) Rochester Code (1892):

In 1892 a batch of botanists headed by N.L. Britton met at Rochester, New York, in the United States and developed a set of rules to govern nomenclature.

These rules, which are based, on modifications of the Paris Code, are commonly known as the Rochester Code and include some new recommendations which are as follows:

(a) Establishment of the type concept to ascertain the correct application of names;

(b) Strict adherence to the principles of priority;

(c) Acceptance of alternate binomials resulting from employment of the principles of priority, even if the specific epithet repeats the generic name, and

(d) Interpretation of priority to apply to the precedence of a name in a publication in addition to the date of publication.

(iii) Vienna Code (1905):

The third International Botanical Congress was held at Vienna in June, 1905.

The new changes included the:

(a) Establishment of Linnaeus Species Plantarum (1753) as the starting-point for naming vascular plants.

(b) Nomina generica conservanda by which generic names having a wide use would be conserved over earlier but less well-known names.

(c) Banning of tautonyms, and

(d) Requirement that names of new taxa be accompanied by a Latin diagnosis.

(iv) American Code (1907):

Being dissatisfied with the results of the Vienna Congress, most proponents of the Rochester Code refused to accept the new rules and in 1907, they put forth a slight modification of the Rochester Code under the heading of the American Code. The first provision was that they would not subscribe to the principle of Nomina generica conservanda or of the requirement of Latin diagnosis, but they accepted the type concept.

Another provision of the revised code was that ‘a binomial may not be used again for a plant in any way if it has been employed previously for another plant, even though the previous use may have been illegitimate’.

Thus the Rochester Code and American Code created two opposing schools of thought in the United States. One was under the leadership of Britton and his students, who followed the provisions of the American Code and the other was under the direction of Asa Gray’s pupils who followed the international rules.

(v) Brussels Code (1912):

The Fourth International Botanical Congress was held at Brussels, 1910. The most significant decision made at this Congress was the establishment of different starting points for priority of names of non vascular plants, the recognition of value of type concept and classification of phraseology of the Vienna rules.

(vi) Cambridge Code (1935):

The basic differences between the Vienna Code and American Code was finally reconciled at the Fifth International Botanical Congress held in 1930 at Cambridge, England and it brought about harmony among the major botanical factions. The new rules legislated at Cambridge constituted the code of nomenclature that was truly international in name and function.

The approved provisions were the following:

(a) The type concept should be pursued;

(b) There should be a list of Nomina generica conservanda;

(c) Tautonyms are not admissible, and

(d) Latin diagnosis is required after January 1, 1932.

(vii) Amsterdam Code (1947):

At the Sixth International Botanical Congress, Amsterdam (1935), a few major changes in the rules was made. It was resolved that “from January 1, 1935, names of new groups of recent plants, except the Bacteria, are considered, as validly published only when they are accompanied by a Latin diagnosis”. An attempt to select a list of nomina specified conservanda was thwarted by an overwhelming vote.

(viii) Stockholm Code (1952):

The Seventh International Botanical Congress met at Stockholm in 1950. It introduced certain number of definitions on types. The word taxon was introduced for the first time to designate any taxonomic group or entity.

(ix) Paris Code (1956):

The Eighth International Botanical Congress was held in Paris in July, 1954 in which great emphasis was laid on types, but the rule of Latin came under fire. It decided that the code should be published in English, French and German languages.

The separation of the Preamble and Principles from the Rules and Recommendations was the major feature of this code. Appendix II (nomina generica conservanda et rejicienda) was amended and supplemented.

(x) Montreal Code (1961):

The Ninth International Botanical Congress held at Montreal in August, 1959 appointed a special committee to study the question of conservation of family names (nomina familiarum conservanda for Angiospermae as Appendix II was introduced). In this code, it was specified that the naming of fossil plants should follow the same lines as that of recent ones.

(xi) Edinburgh Code (1966):

The report of the special committee appointed during the ninth Congress was submitted at the Tenth International Botanical Congress held at Edinburgh in August, 1964.

Some of the important points in the report are as follows:

(a) A.L. de Jussieu’s Genera Plantarum (1789) is the starting-point for family names. Many of the names included in the list are not a matter of dispute, but their inclusion in the list forms a ready reference providing correct names of families together with a type genus for each family.

(b) In the list of nomina familiarum conservanda, a few names are found with a spelling somewhat different from the long-established names, e.g. Cannabaceae for Cannabinaceae, Capparaceae for Capparidaceae, Haloragaceae for Haloragidaceae, Melastomataceae for Melastomaceae, etc.

(c) The rule of Latin for new diagnoses was finally settled and no amendments were proposed at this congress.

At this congress, a committee was set up to prepare a glossary of the main technical terms occurring in the code which resulted in An annotated glossary of botanical nomenclature.

(xii) Seattle Code (1972):

The Eleventh International Botanical Congress was held at Seattle in August, 1969 which proposed the Seattle Code which was edited by F.A. Stafleu and published in 1972. Most of the proposals submitted to the Eleventh Congress were concerned with refinements and increased precision.

The chief issues in Seattle Code include the tautonymous designations of taxa between genus and species and below species, the perennial question of superfluous names and a reorganization of the rules for hybrids. The word autonym (automatically established names) was introduced in this code.

(xiii) Leningrad Code (1978):

The Twelfth International Botanical Congress was held in July, 1975 at Leningrad, Russia and its recommendations came out in 1978.

This Code indicates only small differences from the Seattle Code and includes the following changes:

(a) The concept of organ genera is eliminated for fossil plants.

(b) The Code does not apply to names of organisms treated as bacteria and does apply to all other organisms treated as plants.

(c) The principle of automatic typification is extended to those names of taxa above the family rank that are ultimately based on generic names and the application of the priority principle is recommended while selecting among names thus typified.

(d) A name or combination published before 1953 without indicating the rank is considered validly published but imperative in questions of priority except for homonymy and certain names to be accepted at the varietal rank.

(e) Art. 69 of the previous Code is modified on the basis of type method and Art. 70-71 dealing with discordant elements and monstrosities were deleted, but the Art numbers are retained to facilitate the use of the Code.

(f) The section on orthography is thoroughly rewritten.

(g) Individual paragraphs on all Articles and Recommendations are numbered in a decimal-like system, some being rearranged.

(xiv) Sydney Code (1983):

The Thirteenth International Botanical Congress was held in August, 1981 at Sydney, Australia.

(xv) Berlin Code (1988):

This includes the proposals made at the Fourteenth International Botanical Congress at Berlin, Germany in 1986. Nomina specifica conservanda was for the first time introduced at this Congress.

Two species names, Lycopersicon esculentum P. Miller and Triticum aestivum Linn., have been conserved against the rule of priority, as these names are widely used and any change may create confusion. Articles 66 and 67 were removed.

(xvi) Tokyo Code (1994):

The Fifteenth International Botanical Congress met at Yokohama, Tokyo in 1993. It has been translated into Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian and Slovak. In this code, extensive renumbering had taken place and therefore its preface included a tabulation comparing the placement of its provisions with those of the Berlin code.

(xvii) St. Louis Code (1999):

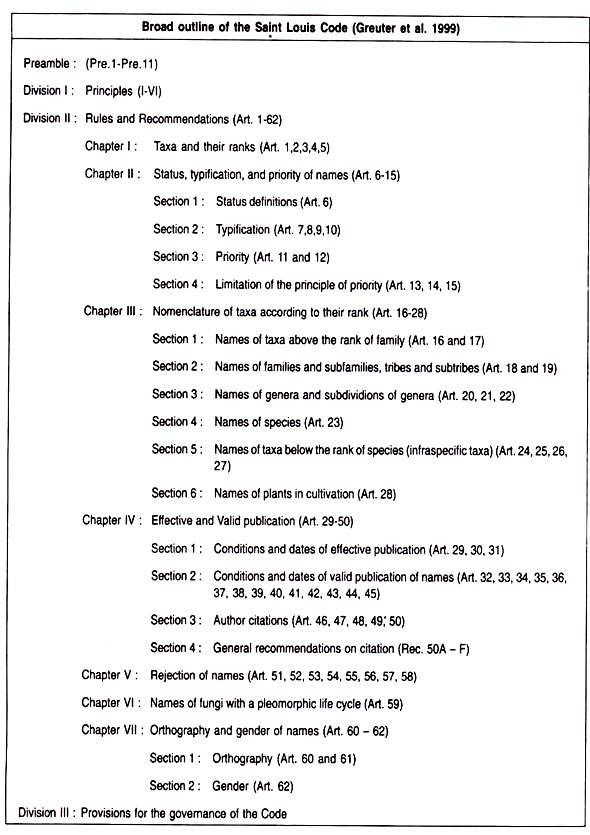

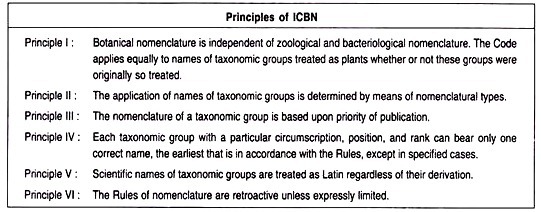

This includes the proceedings of the Sixteenth International Botanical Congress, which was held at St. Louis, Missouri in July-August, 1999 and supersedes the Tokyo Code. Like the Tokyo Code, it is anticipated that the St Louis Code, too, will become available in several languages in due course. The detailed provision of the Code is divided into Rules, set out in Articles, and Recommendations.

The object of the “Rules” is to put the nomenclature of the past into order and to provide for that of the future. Names contrary to a rule cannot be maintained. The Recommendations deal with subsidiary points, their object being to bring about great uniformity and clearness, especially in future nomenclature.

Names contrary to a recommendation cannot, on that account, be rejected, but they are not examples to be followed. The Rules and Recommendations apply to all organisms whether fossil or non-fossil, including fungi but excluding bacteria. A separate code called International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (ICNB) governs the nomenclature of bacteria.

The Seventeenth International Botanical Congress is scheduled to meet at Vienna in 2005.

Rules of ICBN:

(a) Rule of Priority:

It has been found that the number of published names for the various plants exceeds the actual number of taxa. This is because several names have frequently been attributed to the same taxon. Hence, it is very essential to have a way to decide which of the several names should be selected for a particular taxon.

This is where the Principle of Priority comes into play, which insists that each family or taxon of lower rank with particular circumscription, position and rank can bear only one correct name and each taxon is to be known by the earliest name validly published for the taxon, special exceptions being made for nine families for which alternative names are permitted.

Exceptions are also permitted at the family and genus levels, where names are conserved. The correct name for a taxon below the rank of genus, should be a combination of the earliest available legitimate epithet in the same rank with the correct name of the genus or species to which it is assigned, except in certain specified cases.

Although the code recommends that while selecting from among the typified names above the rank of family, the rules of priority should be followed by the taxonomist, it is not mandatory and will not affect the legitimacy of names selected otherwise.

An example of the nomenclatural history of a genus is given below:

Poli/gala L. (1753), Poligala Neck. (1768), Polygaloides Agosti (1770). According to the principle of priority the earliest name, Polygala L., is the correct name for the genus.

(b) Ranks of Taxa:

A taxon is referred to as a taxonomic group of any rank. The early part of the code deals with the ranks of taxa. Every individual plant is treated as belonging to a number of successively higher ranks with the species as the basic unit.

The principal ranks of taxa in ascending sequence are:

Species, genus, family, order, class, division and kingdom. If a greater number of ranks of taxa is required, the terms for these are made either by adding the prefix sub (sub-) to the terms denoting the ranks or by the introduction of supplementary terms.

(c) Typification:

The code has greatly emphasized on typification of taxa in order to bring about stabilization of names. The naming of taxonomic groups is determined by means of nomenclatural types where a nomenclatural type is that element, to which the name of a taxon is permanently attached, either as a correct name or as a synonym. It is not necessarily the most typical or representative element of the taxon.

Following are some of the important nomenclatural types:

(i) Holotype:

It is the one specimen or other element used by the author or designated by him as the nomenclatural type. The holotype is chosen by the original author from a single gathering made by a collector at one time, and expressed definitely at the time of original publication.

(ii) Iso-type:

An iso-type is any duplicate (part of a single gathering made by a collector at a time) of the holotype. For example, if a new species is based on a single gathering that consist of four specimens of the same plant with the same field number placed on four separate herbarium sheets, the original author will designate one of them as a holotype and the remaining three as isotypes.

(iii) Para-type:

A para-type is a specimen cited with the original description other than the holotype or iso-type. For example, if a new taxon is collected in one season without flowers and fruits and the same taxon is collected in a different season with flowers and fruits, then the two collections will be given different field numbers.

Out of these two collections, the author will select one collection as the holotype and the iso-type, while the next gathering cited in the protologues will form the para-type.

(iv) Syntype:

A syntype is one of the two or more specimens cited by an author of a species when no holotype was designated, or it is any one of the two or more specimens originally designated as types (Art. 7.7).

(v) Lectotype:

It is a specimen or other element selected from the original material to serve as a nomenclatural type when no holotype was designated at the time of publication or as long as it is missing (Art. 7.5). If the holotype is lost or destroyed, the lectotype is selected from the isotypes, or, when, two or more specimens have been designated as types by the author of a species, the lectotype must be chosen from among these types.

(vi) Neo-type:

It is a specimen or other element selected to serve as nomenclatural type as long as all of the material on which the name of the taxon was based is missing (Art. 7.8).

(vii) Topotype:

It refers to the specimen collected from the same locality from where the holotype was collected.

(d) Effective and valid publication:

The new name of a taxon is considered valid or effective for publication, only when it is distributed in a printed form to the general public, or at least to ten well established botanical institutions with libraries accessible to botanists generally.

The new name is not considered valid if communicated at a public meeting or by placing of names in collections or gardens open to public or by the issue of microfilm made from manuscripts, typescripts or other unpublished material.

Further, the name of a taxon when published has to fulfil certain conditions for validity. Those that have been published on or after 1.1.1935 must be accompanied by a Latin description or diagnosis or by a reference to a previously and effectively published Latin description or diagnosis of the taxon.

The name of a new taxon of the rank of family or below that has been published on or after 1.1.1958, is valid only when its nomenclatural type is mentioned along with the name of the place where the type specimen is permanently conserved.

Those, that have been published on or after 1.1.1953, are valid only if there is a clear indication of the rank of the taxon and whether it is a new genus, new species or a new combination etc..

(e) Author Citation:

The name of a taxon (unitary, binary or ternary) is incomplete unless the name of the author or authors who first validly published the name, is cited along with it. This helps in verifying the dates of publication and in imparting precision in biological nomenclature.

There are several rules for author citation:

(i) Usually the names are cited in abbreviated forms but never underlined or typed in Italics, e.g.

(1) Vitex Linn.,

(2) V. trifolia Linn.,

(3) V. trifolia, var. simplicifolia Cham.

(ii) These citations can indicate bibliographic references, which are especially helpful in the recognition of homonyms. For e.g. Utricularia caerulea Linn., and Utricularia caerulea Clarice are two names referring to two different taxa, but it would have been impossible for us to recognize this, if the citation of author’s names appended to the respective plant names were not given.

(iii) If the name of the plant is jointly published by two authors, their names should be linked by means of et al or an ampersand (&)

(iv) When more than three authors are involved, citation is normally restricted to the first author and is followed by et al.

(v) If an author validly publishes a name but ascribes it to another person, for example to the author who suggested the name but failed to publish it validly, or to an author who published the name before the starting point of the group, then the name of the latter should be connected to the name of the person who validly publishes the name by an ex as for e.g. Acalypha racemosa Wall, ex Baill.

(vi) If a genus or taxon of lower rank is altered in rank or position, but retains its name or epithet, the name of the author who first published the name or epithet (basionym) must be cited in parenthesis followed by the name of the author who effected the change. This is called double citation, e.g Leucaena latisiliqua (Linn.) Gillis (1974).Basionym: Mimosa latisiliqua Linn.

(vii) If a taxon is of garden origin, then while citing the name it should be ascribed to hort. (hortulanorum) and connected to the name of the author who published it by an ex, e.g. Geaneria dwklarii hort. ex Hook.

(f) Choice of Names:

Following are some of the important criteria for choice of name of a taxon:

(i) When the taxon rank is changed, for e.g., a species becomes a genus, the earliest legitimate name in its new rank is its correct name.

(ii) When two or more taxa of the same rank are united into one, e.g. two or more genera are united, the oldest legitimate name of these taxa should be retained as the name of the united taxon.

(iii)When a genus or a species is divided into two or more genera or species, the original name of the genus or species must be retained.

(iv) When a species is transferred to another genus without the change of rank, the original name must be retained.

(g) Rejection of Names:

A legitimate name or epithet must not be rejected merely because it is inappropriate or disagreeable, or because another is preferable or better known, or because it has lost its original meaning.

However, a name must be rejected if it was nomenclatural superfluous when published. Similarly, a name or epithet rejected is replaced by the oldest legitimate name or in a combination by the oldest available epithet in the rank concerned.

The following types of name can be considered to be illegitimate and unusable:

i. Synonyms:

They are the different names used for the same taxonomic group or taxon.

ii. Tautonyms:

These are names where the specific epithet exactly repeats the generic name with or without transcribed symbol.

iii. Typonyms:

A name is rejected if there is an older valid name based on the same type.

iv. Metanyms:

A name is rejected when there is an older valid name based on another member of the same group.

v. Homonyms:

A name is rejected when preoccupied i.e. identical names cannot be applied to two different taxa.

vi. Hyponyms:

A name is rejected when the natural group to which it applies is undetermined.