In this article we will discuss about Rotifers:- 1. Habit and Habitat of Rotifers 2. External Characters of Rotifers 3. Corona 4. Body Wall and Associated Glands 5. Muscular System 6. Digestive System 7. Nervous System 8. Sensory Structure 9. Excretory System 10. Reproductive System 11. Affinities.

Contents:

- Habit and Habitat of Rotifers

- External Characters of Rotifers

- Corona of Rotifers

- Body Wall and Associated Glands of Rotifers

- Muscular System of Rotifers

- Digestive System of Rotifers

- Nervous System of Rotifers

- Sensory Structure of Rotifers

- Excretory System of Rotifers

- Reproductive System of Rotifers

- Affinities of Rotifers

Contents

- 1. Habit and Habitat of Rotifers:

- 2. External Characters of Rotifers:

- 3. Corona of Rotifera:

- 4. Body Wall and Associated Glands of Rotifers:

- 5. Muscular System of Rotifers:

- 6. Digestive System of Rotifers:

- 7. Nervous System of Rotifers:

- 8. Sensory Structures of Rotifers:

- 9. Excretory System of Rotifers:

- 10. Reproductive System of Rotifers:

- 11. Affinities of Rotifers:

1. Habit and Habitat of Rotifers:

The rotifers are among the most common inhabitants of freshwaters everywhere.

Some also live in brackish water and a few in the ocean or on land in damp sites. They have adopted a variety of habitats and ways of life. Thus, there are creeping, swimming, pelagic and sessile types, as well as carnivores and bacteria feeders. Although the rotifers are generally solitary, some of the sessile species form spherical swimming colonies in which, however, the individuals have no organic continuity.

2. External Characters of Rotifers:

Rotifers or wheel animalcules are minute animals ranging from 0.04 to 2 mm in length and most of them do not exceed 0.5 mm. The rotifer body is generally of elongated form and is divisible into the broad or narrowed or lobed anterior end, usually provided with a ciliary apparatus, an elongated trunk, often enlarged and a slender terminal-region, the tail or foot.

The body is covered with an evident yellowish cuticle that is often ringed throughout or in certain regions. The cuticle may be thickened, chiefly on the trunk to form a hard encasement, the lorica, of one to several plates, that may be variously ornamented.

The anterior end bearing the mouth corona and various projections is not definitely delimited as a head but may be called so for convenience. It is typically broad and truncate or slightly convex, presenting an un-ciliated region, the apical field, encircled by a ciliated zone, the corona.

The head may also bear a pair of prominent lateral ciliated projections, known as auricles. Eyes (pigment spot ocelli) appearing as red flecks, occur singly or paired in the brain, as lateral paired eyes in or near the corona and as paired frontal eyes on the apical field or on the rostrum. The mouth is located in the corona in the mid-ventral line of the head and often coronal protrusion serves as lower lip.

The trunk may be cylindrical or variously flattened and broadened and is frequently enclosed in a lorica, often ornamented or spiny.

Characteristic trunk structures of rotifers are the dorsal and lateral antennae or palps. The dorsal antenna, usually single, sometimes and probably originally paired, is commonly situated in the mid-dorsal line of the anterior end of the trunk and when well-developed is a finger-like projection tipped with sensory hairs. The anus is found in the mid-dorsal line at or near the boundary of trunk and foot.

The body may taper gradually into the foot or the foot may be sharply set off from the stout trunk as a short or long cylindrical tail-like region.

Its cuticle is commonly ringed into a few to many joints. It serves for clinging to objects in creeping types or acts as a rudder in swimming types. In sessile forms, the foot is modified to a long stalk. The foot is reduced or absent in a number of forms, specially those that have adapted to a wholly pelagic life.

The foot is commonly provided at or near its end with one to four movable projections known as toes, used in holding the substratum while creeping. The toes may be short and conical or slender and spine- like. The pedal glands commonly open at the tips of the toes.

In addition to the toes, the foot may bear either similar projections known as styles, spurs, etc. The rotifers are dioecious. In the majority of rotifers, the males are greatly reduced in size and morphology.

3. Corona of Rotifera:

The corona or “wheel organ” is the most striking feature of the rotifers. The ground plan of the corona comprises a large oval ventral field, the buccal field evenly ciliated with short cilia and surrounding the mouth, and a circumapical band extending from this to encircle the margin of the head. The centre of the anterior surface is, thus, left as an un-ciliated area, the apical field.

The circumapical band alters mostly in the direction of enlargement of its marginal cilia with loss of the interior cilia. This tendency is first seen in rotifers with an otherwise primitive corona; as many notammatids, with formation of auricles, a pair of lateral coronal projections provided with long cilia. They assist in swimming and are retracted during creeping.

Further change in this direction leads in some groups of rotifers to the enlargement of the cilia along both margins of the apical band, so that there result two circles of cilia or rather membranelles, an inner or anterior circlet, the trochus and an outer or posterior one the cingulum.

The reduced buccal field becomes incorporated into these circlets and, hence, the corona comes to consist essentially of two circlets of membranelles, with the mouth between them ventrally.

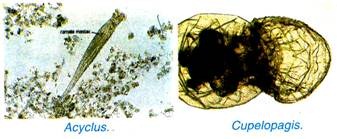

A corona is absent in the adult females of the genera Atrochus, Cupelopagis and Acyclus but is present in normal form in the males and young females of these genera. The corona of male rotifers usually differs from that of females of the same species, being usually less modified.

4. Body Wall and Associated Glands of Rotifers:

The body wall consists of cuticle, epidermis and sub-epidermal muscles. The cuticle, secreted by the epidermis, is not chitinous and presumably consists of scleroproteins. It is frequently divided into rings or segments that lend flexibility permitting a variety of body movements. In many rotifers the trunk cuticle is thickened and hardened into a lorica that, however, is slightly flexible.

The lorica may consist of several pieces or two dorsal or two ventral plates or two dorsal and one ventral or of single dorsal and ventral plates or of one piece with or without a longitudinal suture.

Loricate forms are often dorso-ventrally or laterally flattened; the margins of the lorica may project as teeth or spines and these are subject to much variation within a single species. The part of the lorica covering the neck region may be marked off from the general trunk lorica by a groove which is known as head shield.

The epidermis is a thin syncytium containing scattered nuclei bilaterally arranged and constant in position and number for each species. Around each nucleus or group of nuclei the cytoplasm is heaped up into an elevation projecting into the pseudocoel.

The principal glands attached to the epidermis are the retro-cerebral organ and the pedal glands.

The retro-cerebral organ is situated above and behind the brain and consists typically of a median retro-cerebral sac and a pair of lateral sub-cerebral glands. The duct of the sac forks along with the outlets of the glands open on the apical field, often on a single or paired papilla. Sac and gland vary much in relative and absolute size in different rotifers.

There may be a single sub-cerebral gland or the sac may occur without glands or the glands without the sac. Sac and glands consist of a syncytium and secrete droplets give them a vacuolated appearance. The sac and sometimes also the glands contain strongly diffractive granules, red pigment grains may be present. The function of the retro-cerebral organ is uncertain.

The pedal glands are unicellular glands or multinucleate syncytia located in the foot.

They are numerous, less numerous and reduced to a single pair and often rudimentary or absent in the adults of the sessile orders. They open by ducts on the tips of toes or at sides or base of the toes or on the spurs or at the foot end. The pedal glands secrete an adhesive material used for permanent attachment or in creeping and also in the construction of tubes and cases.

5. Muscular System of Rotifers:

In rotifers, the sub-epidermal muscles consist of a number of muscles found in different parts of the body. In typical cases they are circular and longitudinal muscles. In addition to these body wall muscles there are cutaneovisceral muscles that extend to the viscera, especially the digestive tract, from the body wall, and visceral muscles in the walls of the viscera themselves.

The circular musculature of the body wall consists of a single muscle band, mostly three to seven, widely spaced running close to the underside of the epidermis in a circular direction.

These bands form complete rings but are often very incomplete ventrally, frequently also dorsally, so that they may consist chiefly of short lateral arcs. They occur in neck and trunk, generally absent from the foot and reduced in forms with a well-developed lorica.

The circular bands contain no nuclei, hence, are really part of the epidermal syncytium.

The contraction of the circular muscles serves to extend the body. The circular musculature is specially developed in the head directly behind the corona where it forms the coronal sphincter composed of one to several broad bands and serves to close the neck over the retracted corona. A similar pedal sphincter may occur at the junction of trunk and foot.

The longitudinal body wall muscles consisted originally of bands running the body length directly under the circular bands and attached at frequent intervals to the epidermis. By loss of many of these insertions the longitudinal bands come to run more directly through the pseudocoel and to act primarily on head and foot as retractors.

The principal head retractors are the central, dorsal, lateral and ventral pairs. The lateral is commonly subdivided into three bands, superior, median and inferior. The longitudinal retractors serve to retract the head and corona and foot into the trunk region. The longitudinal retractors have one or more nuclei.

6. Digestive System of Rotifers:

The mouth is rounded, slit-like or triangular, situated ventrally on the head, Beneath the mouth the cingulum may form a definite lower tip. In forms with a large buccal field, the posterior end of the field may project as the so-called chin. The mouth may open directly into the pharynx or may lead to the latter by way of ciliated tube, the buccal tube.

The pharynx or mastax is characteristic and peculiar to rotifers. It is a highly muscular, rounded, trilobed or elongated organ of complicated form and structure, whose inner wall bears the masticatory apparatus composed of hard cuticularised pieces, the trophi. The trophi consist of seven main pieces the unpaired fulcrum and the paired rami, unci and manubria.

The trophi occur in several different types that are correlated with different modes of life. The trophi are of the following types malleate type, virgate type, cardate type, forcipate type, incudate type, ramate type, uncinate type, fulcrate type. The salivary glands are two to seven in number, occur in the mastax wall in many rotifers as uninucleate or syncytial masses with granular or vacuolated cytoplasm.

The function of the salivary glands is uncertain but presumably concerns ingestion or digestion. The mastax is followed by a short or long tube, the oesophagus. The oesophagus is lined with cuticle or ciliated throughout or at the posterior end only. The oesophagus is devoid of glands. The oesophagus is followed by the stomach. It is an enlarged thick-walled sac or tube.

The stomach is provided with muscular layer consisting of muscle cells or if the stomach wall is syncytial there are syncytial muscle fibres. At the junction of oesophagus and stomach occurs a pair of gastric glands, composed of a syncytium having a constant number of nuclei and opening into the stomach by a simple pore on each side.

The secretion comprises droplets or granules aggregated around the pore and presumably enzymatic. The stomach is followed by the intestine. In one case the intestine is tubular and in other bladder-like. The stomach and intestine are attached to the body wall by the usual cutaneovisceral muscles.

7. Nervous System of Rotifers:

The nervous system consists of a main bilobed mass, the brain or cerebral ganglia, sensory and motor nerves from this to adjacent parts, some additional ganglionic masses and two main ventral nerve cords. The brain is a rounded, triangular or quadrangular body lying dorsal to the mastax.

A number of paired sensory nerves extend to the brain from the various sense organs of the head, the eyes, the sensory bristles and pits on apical field, the rostrum and the dorsal antenna. The brain also sends motor nerves to the anterior parts of the various muscles, as the dorsal, lateral and central retractors and to the salivary glands.

The main ventral nerves are ganglionated cords that spring from the sides of the brain and proceed backward in latero-ventral position into the foot. Near the brain they bear an anterior ganglion and farther posteriorly a geniculate ganglion. Posteriorly the ventral cords terminate in ganglia serving the urinary bladder and foot. These ganglia may be fused in one mass, the caudovascular ganglion.

8. Sensory Structures of Rotifers:

The rotifers are richly supplied with sensory cells and sense organs. These occur abundantly on the anterior end in the form of sensory membranelles and styles, ciliated pits, sensory papillae, etc. The sensory membranelles or styles are single stiff bristles situated near the inner edge of the circumapical band and named from their position dorsolateral, lateral and ventrolateral styles.

Similar apical styles occur on the apical field and oral styles may be present near the mouth.

These styles seem to be tactile organs and each is underlined by one or two sensory nerve cells from which fibres go to brain. Paired ciliated pits, apparently chemo-receptors, may occur on the apical field. Conical or finger-like palps tipped with sensory hairs or without hairs may also be present on the apical field. Ocelli, seen as red pigment spots, are of common occurrence.

Usually there is a single, less often paired, cerebral eye, embedded in the dorsal and ventral surface of the brain. Cerebral and apical or cerebral and lateral eyes may be present simultaneously. A sensory organ constantly present in rotifers is the dorsal antenna or tentacle. This is typically a movable papillae or finger-like projection provided at its tip with one or more tufts of sensory hairs.

9. Excretory System of Rotifers:

The excretory system consists of a pair of typical protonephridial tubules provided with flame-bulbs and opening posteriorly into a common urinary bladder. The main tubules extend lengthwise the animal, one on each side, commonly in coils and loops and often fork into an anterior and a posterior branch.

The flame bulbs, usually two to eight on each side, open into a ciliated capillary that enters the end of the main tubule or its branches and may run alongside the main tubule for some distance.

A similar capillary, known as Huxley’s anastomosis may run transversely between the anterior terminations of the main tubules and may receive additional flame bulbs. The flame bulbs vary from a tubular to a flattened triangular form and contain a slender to triangular membranelle of fused, kept in constant motion.

The thickened cap-like end frequently bears one to several protoplasmic filaments that anchor the bulb mostly to the body wall. The flame bulbs are not cells and usually contain no nucleus but are part of the general nephridial syncytium. Posteriorly the tubules open separately into a urinary bladder situated ventral to the cloaca or they unite to a common stem that enters the ventral wall of the cloaca.

10. Reproductive System of Rotifers:

The rotifers are exclusively dioecious. In rotifers, there exists a marked sexual dimorphism. The greatest sexual dimorphism is seen in the order Flosculariacea and Collothecacea where the free swimming males are one-tenth or less the size of the females and have a simple ciliated anterior end in place of the elaborate coronal lobes of the female.

The reduction of males is most pronounced in pelagic and sessile rotifers and appears to be adaptation to ensure fertilisation under these conditions of life. The minute size of males results from the facts that they come from smaller eggs and do not grow after hatching.

In the majority of rotifers, the female reproductive system consists of a single syncytial ovary and syncytial vitellarium bound together in a common membrane that continues to the cloaca as a simple tubular oviduct. The male reproductive system consists of a single large sacciform testis from which a ciliated sperm duct receiving a pair, sometimes more, of prostatic glands proceeds to the genital pore.

The posterior end of the sperm duct is eversible as a cirrus and is lined with hardened cuticle; or it may bear a cuticular tube protrusible as a penis; or the body wall around the gonopore can assume a tubular form and so act as copulatory organ.

11. Affinities of Rotifers:

The rotifers have been allied in turn to almost every invertebrate group, specially the arthropods and annelids.

The idea of arthropod affinity, was based on certain resemblances such as:

(i) Cuticularised surface,

(ii) Apparent segmentation and

(iii) The appearance of jaws and at the same time was strengthened by the discovery of Pedalia whose movable bristle bearing arms suggest the appendages of a crustacean larva.

Hatschek propounded his trochophore theory which maintains that the living rotifers are closely related to the ancestral Mollusca, Annelida and certain other groups. This theory compares rotifers with the trochophore larva and concludes that rotifers are simple -annelids that have remained in a larval state.

At present this hypothesis is based chiefly on the rotifier Trochosphaera whose ciliary girdle, bent intestine and excretory organs resemble topographically the similar parts of the trochophore. But Trochosphaera is merely a peculiar rotifer with a modified girdle type corona only superficially resembling the prototroch of the trochophore is a highly modified corona.

On the other hand the primitive corona was a large ventral ciliated field in no way resembling the ciliary circlets of the trochophore. The annelid theory must, therefore, be regarded as without foundation, as concerns the trochophore resemblance.

The embryology of rotifers suggests that these animals are primitive, not derived by the retrogression on higher forms.

No trace is seen in the development of a coelom or an entero-mesoderm. The anatomy and embryology both incline to the origin of the rotifers from some low- grade creeping bilateral type such as a primitive flatworm. The primitive type of corona may be the remnant of a former complete or ventral ciliation such as found in the Turbellaria.

The formation of cuticularised parts as the trophi is comon among the Turbellaria.

The strongest point of resemblance between rotifers and turbellarians is, however, the protonephridial system which is practically identical with that of the rhabdocoels. The presence of this type of excretory system practically precludes the derivation of the rotifers from any higher group since none of the higher groups have protonephridia with flame-bulbs.

The retro-cerebral organ is probably homologous with the frontal organ of Turbellaria. The division of the female gonad into ovary and vitellarium is another resemblance to flatworms. On the other hand the rotifers differ from flatworms in the presence of anus and the lack of a sub-epidermal muscle sheath and of the sub-epidermal nerve plexus so characteristic of the Turbellaria.

Their small size, however, probably makes such an accessory nerve plexus unnecessary and the nervous system in general bears some similarity to that of flatworms.

On the whole the rotifera show a great resemblance to the Turbellaria than to any other invertebrate group and may be considered as relating the Aschelminthes to the Platyhelminthes. The rotifers display an amazing variety in structure and do not resemble any one group of animals. Hence, the status of an independent phylum to rotifers appears to be justified.