This article provides study notes on conservation of biodiversity.

Meeting Basic Human Needs:

The living world harbours numerous life-forms in all possible natural habitats.

Each of the major ecosystems—viz. Mountains, Forests, Desert, Freshwater, Marine Water, Islands etc.—provided a set-up for evolutionary panorama.

From one-celled organisms to the highest form of animals, from fungus to the large banyan tree, each one possesses unique genetic characters. Human society learnt how to utilize such resources. From the days of hunter-gatherer to the era of Nuke, the range of exploitation of natural resources changed drastically.

But Even Today, the Human Society depends on Biological Diversity for:

The list above may prove the point beyond doubt about the very essentiality of biodiversity. Raw materials have given way to huge varieties of value added products. International trade and commerce, especially from the biodiversity rich countries in the South, depend largely on living natural resource base.

The traditional uses of biological material, as a ten year study on ethno-biology in India carried out between 1982-1992 shows, far out-stretch the modern uses. Indian tribal communities use at least 600 animal species for food and medicine, which are never used by modern biosphere-people (as opposed to the ecosystem people).

The science of agriculture and animal husbandry intelligently utilized the wild plants and animals through a process of domestication, hybridization and breeding. The advent of settled agriculture and animal husbandry secured the food need of the human society.

The varieties of plants—cereals and grain, vegetables, fruits, fibres spices, medicinal and aromatics—provided the vast gene-pool for improvement through selective breeding. Advent of high-yielding varieties of crops and better breeds of cattle and poultry owe much to nature, manipulated with ingenuity of human being.

The need for conservation of biological diversity is, therefore, well-established. Out of 0.13 million species of plants, animals and microorganisms in India, only a handful—not even 200—have been used to feed one billion and meet most of the basic requirements of medicine, fuel, fodder, textiles and housing materials. But the vast genetic resources in the wild store the potential raw material for the future. Prospecting biodiversity has become a part of documentation and inventorisation (Ghosh 2000).

Politics of Biodiversity:

The Convention on Biological Diversity (UN 1992) was signed by 141 countries including India. Later, the number of contracting parties increased to 171. In this Convention, biodiversity of a country has been declared as its ‘Sovereign Rights’ (Article 3) and a mechanism of access and transfer of resources (Articles 15 & 16) with ‘Prior Informed Consent’ and ‘Mutually Agreeable Terms’ (Article 15) has been suggested; it has also been mentioned such a system of ‘Benefit sharing’ (Article 15) between the providers of biodiversity and the users (commercial) should be established.

The application of biotechnology has been advocated but with emphasis on sharing results and benefits arising out of such application with the developing countries (Article 19). The largest economic power, USA, did not sign CBD during 1992 and even when signed later by the then President Bill Clinton, it has never been ratified by USA. Till 2006, as many as 188 parties have joined the Convention.

One may wonder why such an event occurred. It is alleged that the USA, with billions of dollar investment in Biotechnology, (more than 178 billion in one year) did not take chance to commit itself to the regulatory principle of CBD. Later contradiction between the provision of Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) of WTO, supported by the USA, makes it more explicit.

Even the current controversy of Genetically Modified (GM) product and need for precautionary approach was not accepted by USA as it declined to be party to “Bio-safety Protocol”. The power of private monopolies in free market economy can, therefore, make its presence felt strongly.

Politics in biodiversity can be traced back to the very fact of transfer of genetic material from countries in the south to the powerful economies in the north, during the period of colonial rules in South America, Africa, South and South East Asia. One has to remember 12 countries of the world now recognized as “Countries of Mega diversity” have all been under colonial rule (these are countries in Asia, Africa, South America, Meso America and Australia) (Table 2).

One may also recall the controversy over transfer of rice germplasm from the first ever Rice Research Institute set-up in Cuttack, India in the 1960s. When requested by the International Rice Research Institute, Manila, Philippines, to share duplicate rice germplasm, the then Director of Central Rice Research Institute at Cuttack declined; the international pressure supported by powerful Indian lobby saw to it that invaluable germplasm are sent to IRRI without any strings attached. India, like all countries in the south, did not get any benefit for the genetic resources it parted with.

Such outflow of material has now been advocated in the name of cooperation. While materials are being shifted from eco-rich countries, technologies are never transferred from the recipient North to the donor countries in the South.

Politics in Biodiversity appears too deep-rooted. What has been considered to be a purely scientific cooperation for fundamental research without any commercial value turned out to be in the ‘patented product’ regime. The story of Basmati, for which the germplasm was taken from the Indian sub-continent through Rice Research Institute, Cuttack, to IRRI, Manila, is now well-known.

The politics in Biodiversity perhaps reached its peak in the 1990s, when more than hundred patents were issued by the us Patent Office to multinational companies; what was traditional knowledge in India was deemed “New Innovation” in the USA; the list include use of Basmati, Neem, Haldi, Karela, Kali Mirch etc. Fighting a case against such blatant bio-piracy costs money.

As R. A. Mashelkar, Director General of CSIR, says, India (for that matter, any developing country) cannot afford that. It is better to store all traditional knowledge in computer hard disk and made available through web page; this only can prevent bio-piracy trends. All the countries in the tropical South identified as “Mega diversity Country” or with “Hot Spot” areas for crop evolution can do the same (Tables 1 and 2).

However, recent efforts to protect biodiversity based resource and knowledge are noteworthy. India, as a signatory to the CBD, has enacted ‘Biodiversity Act, 2002’ and framed rules in 2004 to implement the provisions of the Act. The Act has set out the guidelines with reference to access to and transfer of genetic resources from India as also stressed on the mechanism of benefit sharing.

Under Section 3 (1) of the Act it has prohibited access to ‘biological resource occurring in India or knowledge associated thereto’ with prior approval of National Biodiversity Authority (NBA), an apex body constituted under the said Act. It has envisaged the system of governance at local level through Biodiversity Management Committee (BMC), at state level through State Biodiversity Board (SBB) besides creating a National Biodiversity Authority.

It has put restriction on bio-survey and bio-utilization for commercial purpose without approval of SBB. However, the rights of the local people and the communities and traditional users (vaids and hakims) have been recognized. Currently, NBA is busy preparing detailed ‘Material Transfer Agreement’, and planning for mega database on Indian Biodiversity besides finalizing a format for People’s Biodiversity Register (PBR). Fifteen states have already formed SBB and the others are on the way (NBA, 2004).

To protect traditional knowledge on Biodiversity based Indian System of Medicine, a massive attempt has resulted in the ‘Traditional Knowledge Digital Library’ (TKDL) incorporating 30,000 Ayurvedic formulations accessible in four major languages. This is a bold step to prevent bio piracy. Similar work is in progress in Siddhi and Unani Systems at NISCAIR, a CSIR institution at New Delhi.

In the international front, a meeting of 12 countries with rich biological resources was convened at Cancun, Mexico in 2002, which resulted in Cancun Declaration of Like Minded Mega diverse Countries (Table 3). Obviously, this list may appear different from the list under Table 2, through deletion of names of Australia, Malaysia, Zaire and Madagascar and inclusion of names of Costa Rica, Venezuela, Kenya and South Africa.

The participating countries at Cancun poses 20 per cent of global area and 45 per cent of the world’s population, but harbour 70 per cent of global terrestrial biodiversity (MoEF, 2006). Member countries of Cancun Declaration committed themselves further in the New Delhi Ministerial Declaration on 21st January 2005 to join efforts for negotiating an international regime emphasizing on ‘Mandatory disclosure of country of origin of biological material and associated traditional knowledge in the intellectual property right (IPR) application’.

This obviously has a strong implication for the mega diverse developing country. One can only wish that if not Australia, the countries of Malaysia, Zaire and Madagascar join this group. It may be noteworthy that a new list of 17 countries including USA is now being considered as the country of mega diversity (Table 4), which has enlarged the scope for further analysis and negotiation, USA, which is not a party to CBD, also finds place in the same list.

Economics of Biodiversity:

How much is biological resources worth ? The subject of “Natural Resource Accounting” is only a recent thought process in the field of ecological economics. The value of agricultural crops, fisheries, fuel and fodder, medicinal and aromatics, textiles and leather, fibre crops and beverages could be a staggering, mind-boggling billions of dollars of international trade.

The oceanic fish catch alone now yields $2.5 billion to the US economy and $82 billion worldwide. A single forested watershed, once lost, could be replaced by mechanical filtration plant costing $6-8 billion. Removal of 20% trees in large urban area could lead to storm water runoff and flood; to control such flood due to deforestation, would require $2 billion investment. The over the counter cost of drugs from plants alone was estimated to be $20 billion in the USA and $84 billion worldwide in 1998 (Wilson, 2002).

Of the 14 major items of exports from India, at least 10 could be labeled as of ‘biological origin’; these include agricultural products, spices, beverages, textiles, marine food-fish, medicinal and aromatics etc. A biodiversity profile with more species that live together is now said to contribute to more stable and productive ecosystem. Enrichment of biodiversity can increase productivity and over-yielding. Economic valuation of such over-yielding becomes too obvious.

Strangely, when one single gene from dwarf Mexican wheat was recombined by a University of Wisconsin scientist, American wheat growers expected additional profit of $100 million in one single year. Mexico, however, did not gain a single dollar out of that! At least 27 us patents were obtained by five multinational companies, in mid 1990s, on new formulation of drug based on bio-active ingredient of soil microbial organisms, all of Indian origin.

Neither Mexico nor India could benefit from such wonderful innovation in the area of food and medicines. Depending on biological resources and emerging field of biotechnology, single largest investment is made in BT arena comparable to IT.

The people in the tropical countries, especially in cut off areas like islands, may depend for 100 percent livelihood income from biological resources. Lakshadweep Islands in India depend solely on Coconut palm and Tuna fish for economic stability. More than 132 villages around Asia’s largest coastal lagoon, Chilka, survive on fishery related income.

The assessment of values of goods and services from biological diversity has never been made in a holistic manner or even on ecosystem basis. Serious researches are needed to assess the total contribution from Agriculture and Animal Husbandry sector, as also from Fisheries, Forest, Energy, Textile, Beverage, Medicinal sectors to the national and international economy. Add to this the continuous utilization of vast, wild genetic resources in food, medicine and textile sectors.

Issues in Conservation of Biodiversity:

The Major Issues in the Biodiversity Discussion can be put under:

(1) Assessment – how many or how much is known? How much to be explored ?

(2) Threats – major causes for biodiversity depletion, making many species extinct, rare, endangered or vulnerable.

(3) Conservation Strategy – right pathway to protect and augment biodiversity as also sustainable use pattern, including people’s involvement in conservation.

(4) Bio-safety and Bio-ethics — adoption of precautionary approach specially in Genetically Modified (GM) food, beverages, textiles promotional work. Ethical implication of tinkering with nature.

5.1 The Assessment both at National and Global levels have been made. While 1.4 million species, so far documented globally, is said to be not more than 5% of the biodiversity (largely unknown element come from invertebrates and lower organisms), India has 0.13 million species (and may well host over half a billion species if one interpolates the data from global estimate).

5.2 The major causes of Threat and loss of biological diversity are:

(a) Habitat destruction or fragmentation,

(b) Pollution,

(c) Mass scale deforestation and loss of wetlands. Development without environmental impact assessment (EIA) led to emergence of concept of considering Biodiversity as a part of EIA.

5.3 The government led policy of ex-situ and in-situ conservation remains the mainstream Conservation Strategy. The setting up of gene banks, botanical gardens, zoological gardens and aquaria have helped to conserve many a species, now extinct from the wilderness area. Such methods of ex situ conservation apart, creation of protected area (PA) in every bio-geographic realm and ecosystem helped to conserve both representatives ecosystem and species and, in turn genetic diversity; in-situ conservation areas opened up the avenue for eco-tourism to the National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries, Tiger Reserves, Biosphere Reserves, National Lakes, Coral Reef, Mangrove areas, as also to the Marine (National Parks) areas.

But most of these measures to set-up PA’s due to faulty methods made local people alienated, especially in countries like India. People’s participation has been tried through Forest Protection Committees (FPCS) and Eco-Development Committees (EDCS), largely as a part of Joint Forest Management (JFM) programme. Efforts have been made to augment biodiversity by economic development of forest-villagers in seven Tiger Project areas of India under ‘India Eco Development Project’ (IEDP) including one in Buxa Tiger Reserve in North Bengal. Results are yet to emerge.

On the other hand, faulty government policy driven by market economy led to serious crisis in such vital resource base like Lake Chilika. Debarring villagers to practice traditional fishery and introducing prawn culture nearly killed the lake, changed its biological profile and led to sharp decline in capture fisheries. Fortunately, a change in policy seems to help recover the lake system.

People’s participation in documenting local biodiversity by a process of empowerment has been witnessed in South India. Through the efforts of Indian Institute of Sciences, Bangalore, led by Prof. Madav Gadgil, such a process led way to others.

In West Bengal, ENDEV-Society for Environment and Development after having completed a pilot project in South Bengal has now initiated ten village oriented programmes to document biodiversity and current uses. In both the areas, local students and teachers become the main human resources to be trained.

The West Bengal project supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) under Global Environment Facility’s (GEF) small grant component, has involved 100 students from five villages in Nadia district and another 100 students from five villages in South 24 Parganas.

At the end of such programme, village level ‘People’s Biodiversity Register’ (PBR) will help to claim over the rights of local resources by more than 15,000 villagers of 10 villages; a Biodiversity Resource Centre at each of the districts, as planned, may help to continue the programme for long term.

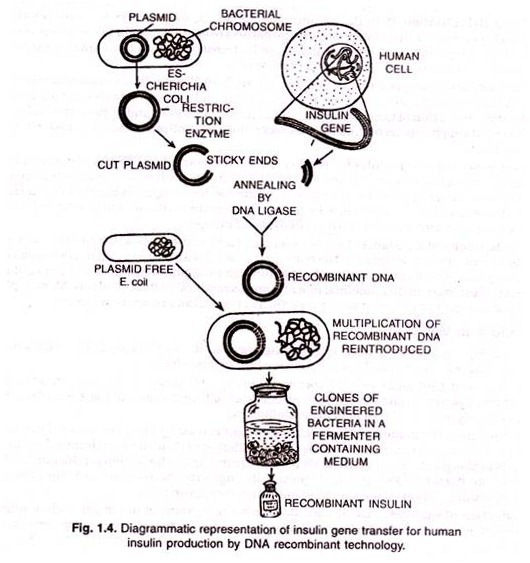

5.4 Concern for Bio-safety have been noticed in India since 1990, followed by the inclusion of “Bio-safety and Recombinant DNA guidelines” in the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. Later, these guidelines have been revised by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), with the aim of conservation of biological diversity (in 1994) to accommodate safe handling of ‘Genetically Modified Organisms’ (GMOS) in research, application and technology transfer.

These include control of large scale production and deliberate release of GMOS (plants, animals) and products into the environment. No Secretariat has been established yet to monitor the trial of GMOS. Implementation work is presently controlled by various Adhoc Committees. But above all, the public concern and participation, which is the major need at this stage, has not yet reached the required level.

Fear and Apprehension:

(i) Plants (genetically engineered) that produce vaccines or drugs, may be transported without application of ‘Advanced Informed Agreement’ (AIA) and Risk Assessment.

(ii) GMO’s entering developing countries in different Food-Aid-Programmes (non- marketable harvest being brought by the Government and used).

Bio-Safety Protocol:

The prior attempts that were made in respect of bio-safety culminated in the Cartagena Protocol that has been adopted on January 24, 2001 in Montreal, Canada, in the presence of 130 participatory countries. Here, an attempt has been made to determine the environmental impact of bio-engineered products, i.e., the Living Modified Organisms (LMOS). The USA is not a party in this agreement but has participated in the “Miami Group of Agricultural Exporting Nations”.

In the present day, the biotechnological products are intended for introduction into the environment as well as in the market, for example, seeds for planting and fish for stalking. Moreover, increasing demand for food and feed also influences the replacement of those commodities by LMOS for direct use as food and feed or for food processing (LMO-FFP).

In this scenario, the Bio-safety Protocol calls for a ‘Precautionary Approach’ by confirming the right to take decisions in case of import. It deals with the regulation for Trans-boundary Movement of specific categories of GMOS. Some other contributions of this Protocol are : the right of countries to protect themselves in an informed way and establishment of an internet-based ‘Bio-safety Clearing House’ (BCH).

This would help to make decisions on importing lmos. This Protocol has also established an ‘Advanced Informed Agreement’ (AIA). The AIA involves a procedure, which ensures that the party of export shall notify the competent authority (of party of import) prior to International Trans-boundary Movement (this includes identification method, centre of origin, risk assessment report etc. as provided in Annexure I).

The party of import has to confirm receipt of the notification within 90 days. But, any failure to acknowledgement does not mean consent. Though there are provisions for labelling and segregation, the protocol does not warrant labeling.

Some other key Aspects of this Protocol can be Summarized as:

(i) Definition of GMOS—LMOS.

(ii) A National authority has to be formed as CPB focal point.

(iii) Pharmaceutical LMOS are exempted.

(iv) Technical assistance for capacity building.

It may be noted that the Protocol officially called Cartagena Protocol came into force on 11th September 2003 and, till July 2006, 134 parties have ratified the Protocol.

Bio-Ethics:

Biodiversity Conservation may pose some strong ethical issues. These ethical arguments have roots in the value systems of most religions, philosophies and cultures and thus can be easily understood by the general public. They appeal to a respect for life, a reverence for the living world and a sense of intrinsic value in nature. Ethical arguments for conserving biodiversity appeals to the nobler instincts of people and are based on widely held truths. People will accept these arguments on the basis of their belief systems.

These ethical arguments can be categorized into two broad categories viz., Nominative and Non-Nominative. The nominative ethics are nothing but the ‘Prescriptive Ethics’ which can be exemplified as taking moral position by formulating and defining basic principles and virtues towards moral life that may lead to the ethical regulation of modern biotechnology. Such ethical principles have been adopted in countries like Austria, Russia, New Zealand etc.

On the other hand, the Non-Nominative ethics can be broadly classified into ‘Descriptive Ethics’ and ‘Meta-Ethics’. In descriptive ethics, the morality is used to describe and analyze in a simple manner without giving judgment for the same. As for example, studies on consumer acceptance and public attitude towards biotechnology can be cited.

In this case, the task would be finished with simple display of findings of such studies. Meta-ethics is used in a broad sense and it deals with the examination of the logical structure behind any normal reasoning and it also includes the justification and inference part. Moreover, in meta-ethics, the position in bio-ethical defects is critically analyzed to find out whether it has any strong coherence with some basic principles.

At present, the same ethical issues are raised in advanced biotechnology, e.g. Human Reproduction, Gene Therapy, Prospective DNA sequence, Gene Transfer and Cloning (in Animal Biotechnology) and also topics like Bio-safety, International Property Rights (IPR) and Biodiversity (in case of Plant Biotechnology).

To dissolve the conflict, an “International Bio-ethics Survey” has been conducted in 1993 involving countries like Australia, India, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Philippines, Russia, Thailand, Singapore, Hong Kong etc. In this survey, an attempt was made to find out the benefits and risk factors involved in genetic engineering.

All of us know that the genetic mutations might occur both naturally and by manipulation. The natural gene alterations are few and occur due to the course of ecological adaptation, whereas most of the man-made alterations are intentional.

In the above perspective, one of the major emerging issues is the labelling of genetically modified products which may enable a member of the public to choose. Food and feed commodities can be easily labelled in a positive or negative manner. Positively labeled commodities indicate the presence of GMOS, whereas the negatively labeled ones may declare the absence of GMOS.

A pioneering attempt towards the enactment of a code of ethics was made by the UNESCO in 1993 through the formation of an “International Bio-ethics Committee”. The final version of the directive was discussed in a general assemblage of 187 countries of UNESCO. The final outcome of this effort was passed by the UN General Assembly as “International Declaration in Human Genome and the Protection of Human Rights” in 1998.

Apart from this, the European Countries Jointly Formulated some Bio-Ethical Codes, which can be Summarized as:

(i) Prevention of any attempt to cloning of human being.

(ii) Ensuring the people’s concern for animal welfare.

(iii) Prevention of any attempt to use biotechnology for weapon making.

(iv) Ensuring the right to privacy of information.

(v) Restriction on gene alteration in human sperm.

(vi) Restriction of clinical trial only on prior informed consent.

(vii) Ensuring transparency of product information.

(viii) Ensuring conservation of genetic and biological diversity.

(ix) Ensuring safe transfer of technology.

Impacts of Globalization on Biodiversity:

The impacts of globalization on biodiversity can be analyzed from specific sectors. Agro biodiversity in particular has undergone significant changes during post-Green Revolution period. Vast genetic resources, specially the farmers’ varieties, have given way to the lure of high yielding varieties (HYV).

The open market economy since 1991 has again been casting serious doubt on the government’s farm policy; the sequence of new Agricultural Policy 2000, Plant Varieties Protection and Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001, and now the draft Seed Bill, 2004 are all working at cross-purposes. ‘Corporate Efficiency’ is being advocated in the name of privatization and contract-farming; sell of miracle seeds (GM seeds), which are 20 times costlier in some cases, caused frustrations and havoc in the cotton fields of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra in recent times. Debt burden farmers are increasingly becoming suicidal.

Now the proposal to ban, save, exchange and barter farmers’ seed unless they are certified will be a positive disincentive for conservation of agro biodiversity and it acts contrary to the very spirit of CBD and the National Biodiversity Act of India.

This is being proposed in spite of several round of serious consultations held at National Institute of Rural Development, Hyderabad, 2002, National Biodiversity Authority, Chennai, 2006, and, more recently-held International Policy Consultation to provide incentive for supporting on-farm conservation and augmentation of agro biodiversity through farmers’ innovations and community participation held at Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, 2006.

While globalization process has direct impacts on agro biodiversity in the developing countries, the WTO prompted Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (trips) further undermines the very basis of conservation of biodiversity and traditional knowledge. This can be evidenced from the following Box 1.

The monopolistic shift to private institutions obviously sharply contradicts the basic principles of benefit-sharing between the conservers and providers of biodiversity, both material and knowledge, and the commercial uses of such resources through private capital (Ghosh, 2003).Tasks ahead are difficult but not impossible but only a strong political will and massive public support to establish the logical rights can possibly help to resolve the crisis.